Jack Dempsey’s Long Goodbye (Part 2)

This is the second of two articles detailing Jack Dempsey’s comeback tour. For Part One, click here.

Dempsey took a brief break from the first leg of the tour for the divorce hearing. After failing to reach a settlement, Jack finally filed for divorce in Reno while Estelle filed her own case in a Los Angeles court. In September, after a hearing that had Dempsey on the stand for twenty minutes, the court granted a divorce with a default decree. Estelle was not represented as she was pursuing case in California, but she eventually agreed to accept the Reno divorce and withdraw her suit. In the end Estelle received $30,000 for herself, $10,000 for her lawyers, and the $150,000 mansion in Los Angeles with all its furnishings and paintings, plus three cars.

Dempsey later stated that, “I resented her more than I disliked her. In fact, I would have taken her back if she had snapped her fingers.” Estelle was not so forgiving. Not long after the divorce a fan approached for an autograph. As Estelle signed her name she noticed Dempsey’s autograph was already at the top of the same page and she remarked, “This is the last time that son-of-a-bitch is on top of me.”

Starting the second leg of the barnstorming tour in Provo on November 6, 1931, Dempsey was in a weakened condition. Between the first two legs of the tour he had hunted moose and played golf, but he had also spent five days in bed with influenza. On this leg he fought 32 opponents in thirteen cities. He beat three fighters in Provo and whipped three more in Des Moines.

But Dempsey had a difficult time at the next stop, fighting Edward “Bearcat” Wright in Omaha. Although he won the decision, Dempsey’s legs were so weak that he felt they could barely support him as he waddled around after “Bearcat.” By the end, the crowd of eight thousand was booing Dempsey and loudly cheering Wright. In fairness to Jack, it should be noted that “Bearcat,” unlike most of the other comeback tour opponents, was a serious pugilist with wins over Jack Johnson and Sam Langford on his record.

Even so, it was nearly as bad in Moline where Dempsey was again jeered as he went the distance with two heavyweights, one of whom managed to open a cut over Jack’s left eye. But while he appeared tired and dejected, the man they once called “Kid Blackie” still outclassed his two opponents. Dempsey turned in better performances in the remaining bouts in Kansas City, Wichita, Tulsa, Phoenix, Fargo, Duluth, St. Paul, Winnipeg, and finally in Sioux Falls in December.

Critics were quick to dismiss the barnstorming bouts as comical and Dempsey largely agreed with them. Boxing several opponents in a single night, none of whom would have lasted more than a round with him in his prime, became embarrassing for the ex-champion. He had fought in million dollar gates and was now climbing into the ring against nobodies. It was not “easy money,” and Jack later wrote that he found it all “somewhat humiliating.”

As Dempsey suspended the tour just before Christmas in 1931, rumors of big fights against top heavyweights gathered steam. There was speculation matches were in the works against Sharkey, Carnera, or Ernie Schaaf, all culminating in a title bid against current champion Max Schmeling. The talk was that paydays of up to half a million were being discussed. Madison Square Garden proposed that Dempsey fight a top opponent in February 1932, followed by Sharkey in May or June, and then Schmeling in September. Jack told the press, “I can flatten any man I meet,” and that some of the fighters he had faced thus far on the tour, such as Babe Hunt, Charley Retzlaff, and a few others, were “pretty good” boxers.

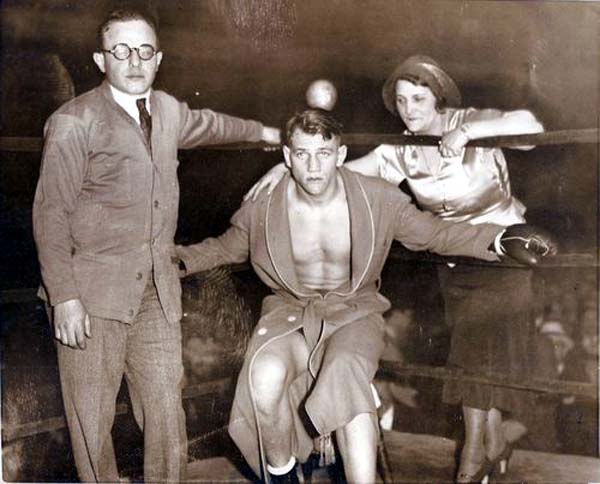

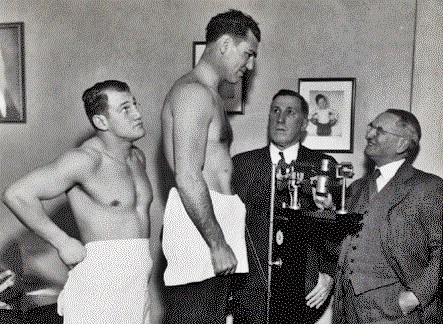

The tour resumed on February 1, 1932 with two bouts in Stockton, after which Dempsey went east to Milwaukee, Cleveland, and Flint. But the comeback reached a crossroads in Chicago in mid-February. The true test of Dempsey’s worth was to be decided in a bout against King Levinsky who owned a rather spotty record of 41-15-4. Despite this, the match presented a legitimate challenge. Levinsky was a young, hard-hitting heavyweight with victories over Tommy Loughran and Paolino Uzcudun, and he had recently gone the distance with Max Baer in Madison Square Garden. A win over Levinsky would show Dempsey was still a viable force and propel him towards bouts with Sharkey or Scheming; a loss would leave his comeback at a dead end.

There was a great deal of excitement in Chicago as the popular former champ prepared to face Levinsky, with a crowd of three thousand filling the Arcade Gymnasium just to watch him train. Lena Levy, Levinsky’s sister and manager, told the press that while Luis Firpo had only knocked Dempsey out of the ring, her brother would knock him out of the building. On February 18th, a crowd of some twenty-three thousand, a record for an in-door boxing match in the city, filled every corner of Chicago Stadium. Thousands more lined up outside hoping for a stray ticket. The gate for the bout was almost seventy-five thousand, with Dempsey pocketing thirty grand while Levinsky got ten.

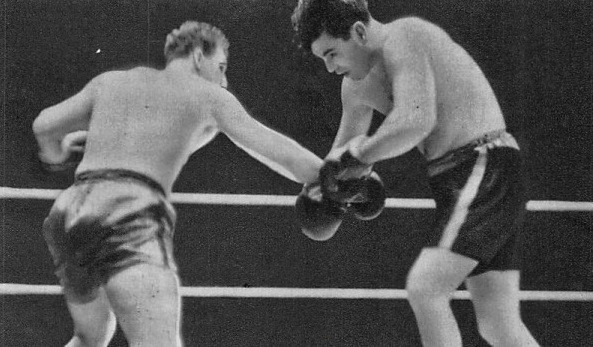

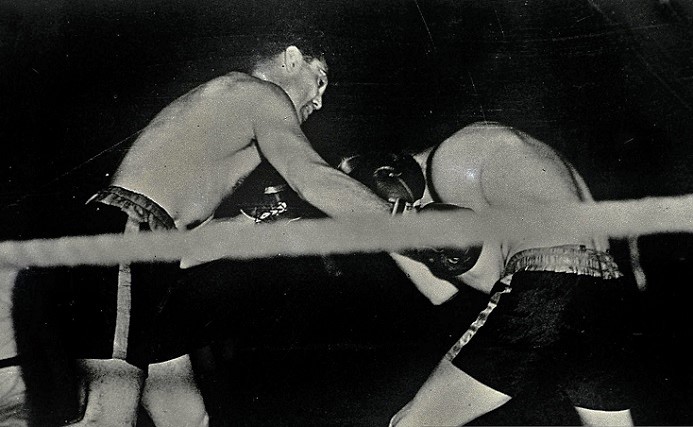

The bout was reported to be a “slugging match,” with plenty of toe-to-toe action. But over four furious rounds, it was not the erstwhile “Manassa Mauler” who imposed his will, but instead the younger Levinsky who out-slugged the once-fearsome Dempsey. A reporter wrote that Levinsky was crude, powerful, and fearless, hitting Jack as he pleased while taking all the ex-champion could offer. Jack was “dead game” but the old bobbing-and-weaving style, the aggressive stalking and cat-like speed, were all reduced to a ponderous shuffle. Dempsey later said that Levinsky had two advantages over him: youth and enthusiasm. Jack had to finally face the fact that his heart just wasn’t in it anymore.

According to accounts, by the fourth and final round Dempsey was in “sad shape,” and with the clock winding down, Levinsky stood in the middle of the ring and confidently motioned for Jack to come and fight. Had Levinsky been a more skilled boxer, or had the bout gone for two or three more rounds, Dempsey might have been knocked out. The heated action continued after the final bell with referee Eddie Purdy having to pull the fighters apart.

The winner was decided by the reporters at ringside: eighteen voted for Levinsky, two for Dempsey, and four had it even. According to his own account, as the bout ended Jack realized he “no longer had any business being in the ring.” He was through. Afterwards Levinsky told reporters that Dempsey, “ain’t so hot, but he can still punch.”

As he took off his gloves in his dressing room, Dempsey knew he had been whipped. He was only a “shell of the fighter who once had been champion” and he had to admit he was lucky to have been slapped around by Levinsky. Had he been boxing Schmeling or Sharkey, he would have been knocked out. But while Jack finally accepted that his boxing days were over, he still had contracts to fulfill for exhibition bouts. He would have to finish the tour.

Five days after losing in Chicago, Dempsey won a decision over Frankie Wine in Louisville and then fought fifteen opponents in a little over three weeks in Dayton, Cincinnati, Columbus, Akron, Toledo, Clarksburg, Huntington, and Toronto. While his business manager continued to talk up the possibility of a bout against Primo Carnera and speculated that the exhibitions could continue for the next two years with tours of Australia, South America, and the Philippines, Jack had decided otherwise. He was done.

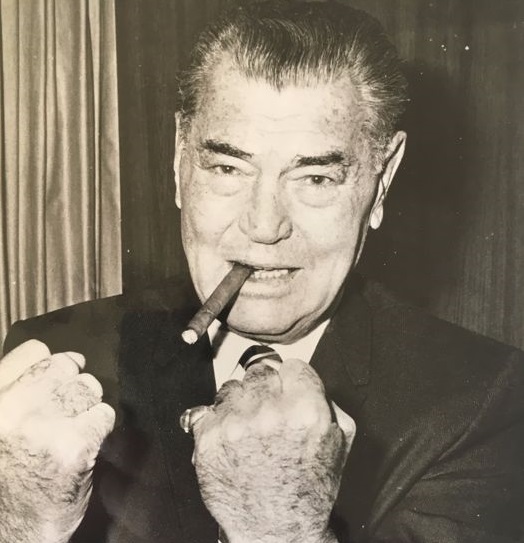

Dempsey finally ended his comeback tour once and for all with a four round win over Babe Hunt in Detroit on March 31, 1932. He had the crowd of fifteen thousand on their feet as he pursued Hunt in the final round and battered him with heavy shots. And that was it. Dempsey quit the ring for good and immediately resumed promoting, refereeing, and performing in vaudeville. He later served in the Second World War, and owned a successful restaurant in New York City for a number of years. An icon of a more glamorous age, Jack remained a popular celebrity for the rest of his days. He died in 1983 at the age of 87.

On his comeback Dempsey had boxed exhibitions in forty cities against 103 opponents, winning all but the Levinsky bout. Although estimates in the press varied widely, over the course of the many shows he drew over 300,000 spectators, with an estimated total gate adding up to more than $700,000. As Dempsey’s take was just under half the gate at most shows, he probably earned roughly $350,000, the equivalent of over six million in today’s dollars. The barnstorming tour may not have seen a return to championship form for the former heavyweight king, but it had proven financially lucrative. The tour enabled Jack Dempsey to live the rest of days in a manner befitting a living legend and one of the greatest boxers in heavyweight history. — Thomas Dade

It’s strange to see Levinsky described as ‘fearless’, although I hasten to add that no man who lacks courage ever entered a boxing ring, at least not more than once. The better-known description of Levinsky’s grit in the line of fire, is of him cowering on the bottom rope in round one against Joe Louis, imploring the referee to, “Please don’t let him hit me again”.