March 31, 1980: Tate vs Weaver

Not for nothing do they call boxing “the cruelest sport.” Just as a baseball game can end with a single crack of the bat, one hard blow can not only decide the outcome of a fight, but the trajectory of a human life. In boxing, unlike other sports, real tragedy is inherent, only a punch away, the cruel whims of Fortune and hard luck sometimes deciding a boxer’s fate as much as any lapse in strategy or execution. It can be agonizing to witness. And yet, paradoxically, this vicious cruelty lies at the heart of the sport’s primal appeal: the chance to witness the bravery of those risking everything for the glory of battle and victory.

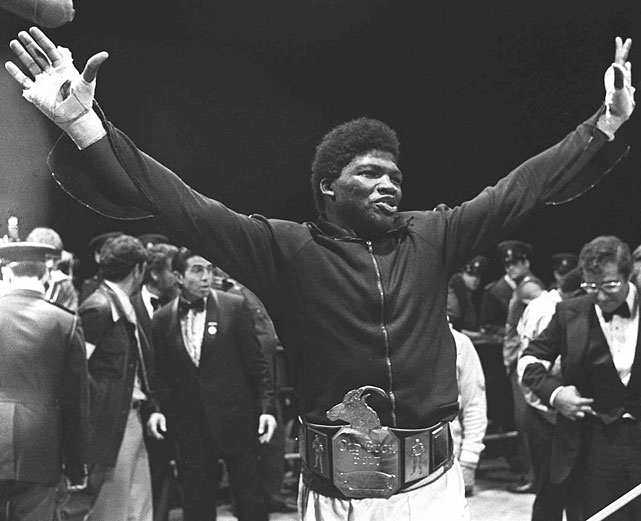

It’s 1980. Boxing is bigger than ever, but the heavyweight division struggles for cohesion. Less than two years before, after a long and incredibly successful run, Muhammad Ali had announced his retirement. These were the days when the so-called “alphabet wars” began in earnest with competing sanctioning bodies starting their insidious work to debase what little integrity pugilism still possessed. With Ali’s departure, there were now two claimants to the heavyweight throne: Larry Holmes held the WBC (World Boxing Council) title, while the WBA (World Boxing Association) belt had been secured by John Tate.

Tate had signed promotional contracts with Bob Arum and the promoter was working to position the huge Tennessee fighter and Olympic medalist as the heir apparent to Muhammad Ali. Despite the fact Holmes had obviously faced tougher competition, the former sparring partner for “The Greatest” could not shake his image as a poor man’s Ali, a boxer with great talent, but lacking in charisma and mass appeal. And so, while the public remained cool to “The Easton Assassin,” Arum moved to capitalize and turn Tate into a star, a hero, the next great American heavyweight.

Thanks to Ali’s immense popularity, the success of the “Rocky” movies, and the stirring victories of American boxers at the 1976 Olympics, professional boxing was now attracting huge television audiences and big money. Arum, working with ABC television, helped engineer an unprecedented prime-time television special, with Larry Holmes, Marvin Johnson, Eddie Gregory and Sugar Ray Leonard all in action on the same night. For Arum though, the night’s showcase bout was John Tate vs Mike Weaver. Few had witnessed any of Tate’s previous fights and Arum was counting on an impressive showing in the Knoxville native’s first title defense to vault the 24-year-old into prominence.

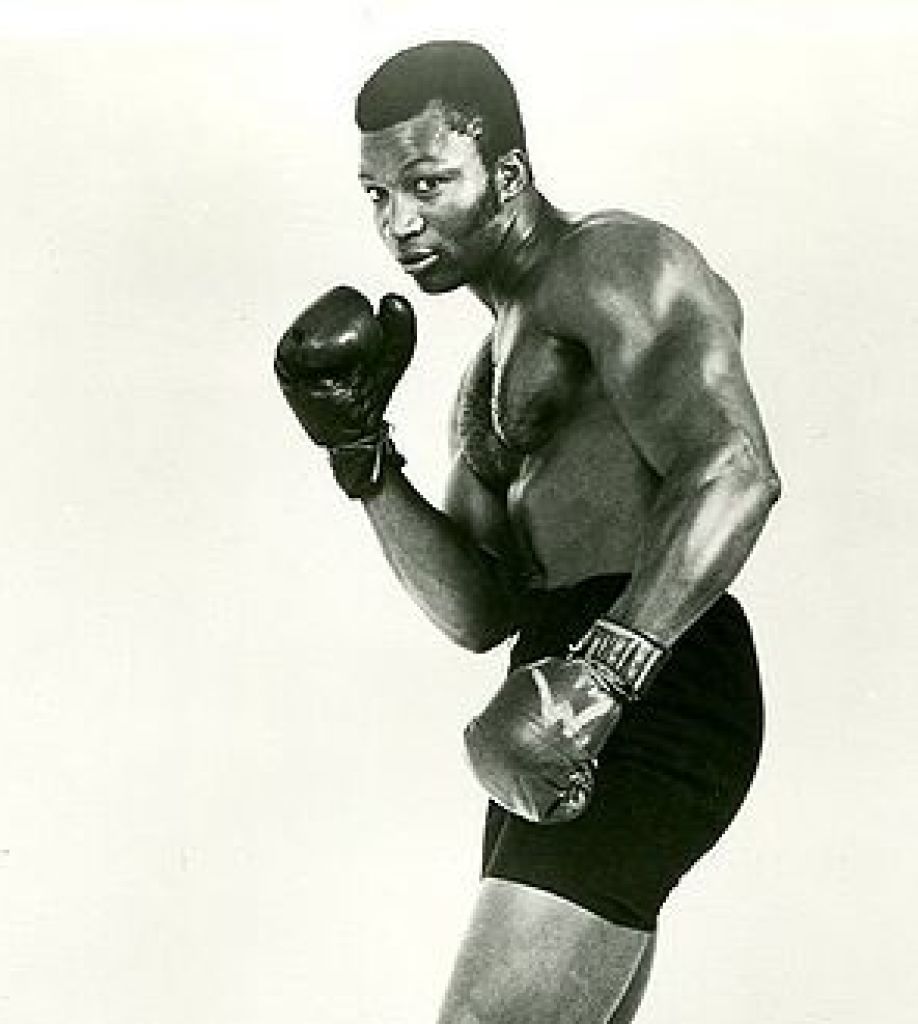

Tate’s opponent for this task had been carefully chosen and Mike “Hercules” Weaver seemed a safe bet. With a record of 21-9, he figured to lack the talent to upset Tate. But more to the point, Weaver had surprised everyone the year before when he gave Larry Holmes one of the toughest fights of his career. Arum’s intention was to use an impressive win over Weaver, in front of a Knoxville, Tennessee crowd, to position Tate as the true heavyweight champion in the public eye. And when the bell rang for round one, there was little reason for Arum not to be confident of his plan.

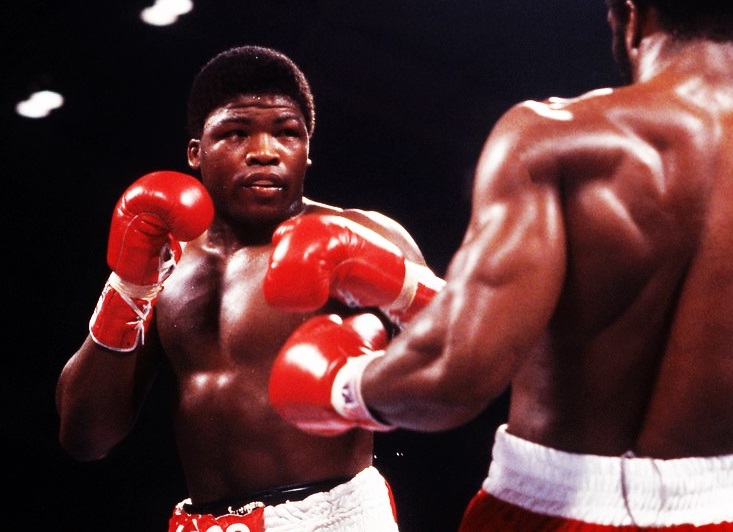

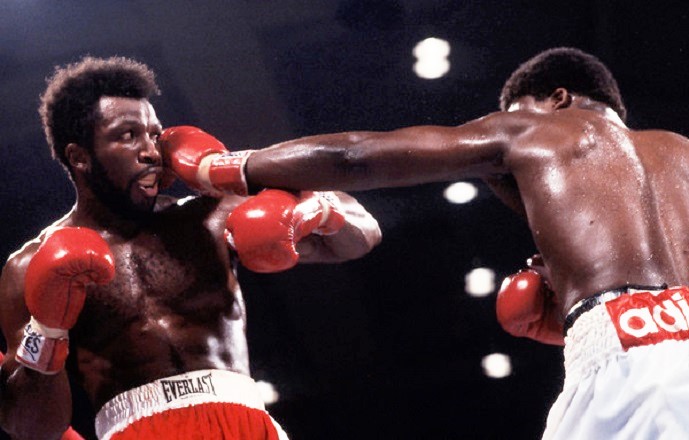

Tate enjoyed significant physical advantages over Weaver; younger and quicker, he was also taller and 25 pounds heavier. The champion used his superior size and weight, along with a snapping jab and a jarring right cross, to physically dominate and win almost all of the first ten rounds. Chanting Big John Tate! Big John Tate!, the hometown crowd spurred the champion on as he set a fast pace, one Weaver appeared unable to match. Indeed, the challenger was boxing like a man who had just awakened from a deep sleep, and as the bout progressed his corner became increasingly frustrated with their listless fighter. “You’re not throwing any punches,” complained Weaver’s manager, Don Manuel, after the ninth round. “You got no chance to win if you don’t throw some punches!”

Weaver briefly came alive in a thrilling round twelve, staggering Tate with a left hook and controlling the action, but then, inexplicably, he failed to follow-up his success in the two rounds that followed. As the fighters readied themselves for the final three minutes, everyone knew Tate had a huge lead on the scorecards. One round more and the victory was his, and Bob Arum could start crowing about who was the real heavyweight champion of the world. Just before the bell, Manuel leaned over the shoulder of an exhausted looking Weaver and said, “Go out there and knock him out. If you don’t, don’t come back.”

The words appeared to resonate. Showing more urgency and energy than in any previous round, Weaver chased after the champion, belying the experts who said he lacked the stamina to go the distance. Tate retreated, looking to simply survive the final three minutes instead of standing his ground, a grave mistake as it gave the desperate challenger momentum, allowing Weaver to come forward and put more weight behind his punches.

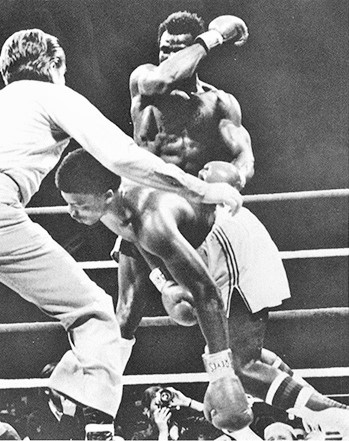

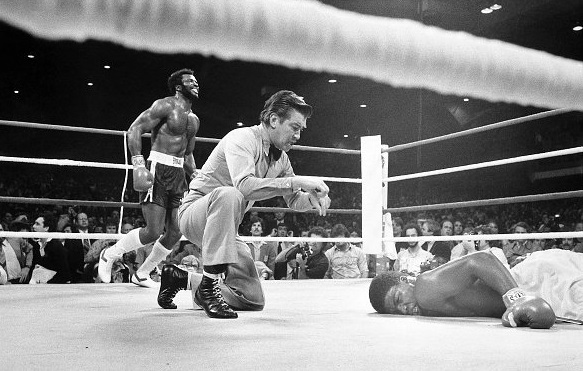

With just a minute left in the fight, Weaver landed a hard right hand followed by a left and a tiring Tate backed into his own corner. The champion clinched and Weaver pushed him into the ropes, dug a right to the body, and then slammed home the biggest punch of his entire career, a crushing left hook that landed perfectly on Tate’s jaw and instantly rendered him comatose. All 232 pounds of the suddenly unconscious champion hung suspended for a brief, breathless moment, before they toppled, falling lifelessly, like a condemned skyscraper collapsing after all the charges have blown. Tate landed on the floor face first, out cold. Finished. Done. Along with all of Bob Arum’s big plans.

A single punch striking just at the right moment on Tate’s jawbone changed irreversibly the lives of two men, and thus Weaver vs Tate stands as one of the greatest of all one-punch knockouts. The new champion, who had been viewed short months before as a fringe contender, went on to be a force in the heavyweight division for close to a decade, holding the WBA belt for three years before losing it in controversial fashion to Michael Dokes.

By contrast, Tate suffered another knockout loss the following June, was subsequently released by Arum, and never regained his championship form. His ring earnings dwindled away and he served time in jail for theft and assault. He mowed lawns and did odd jobs to make ends meet. Addicted to cocaine, in 1998 he suffered a stroke while driving and was killed when his truck struck a utility pole. Before that he had been seen panhandling on the streets of Knoxville, the same city where he had once fought as heavyweight champion, where thousands had cheered him on and chanted “Big John Tate! Big John Tate!”

Not for nothing do they call boxing “the cruelest sport.”

— Michael Carbert

Remember watching this as a kid with my older brothers. I remember it because of the title fights you could watch on network tv for free. Tate was winning easily, but in boxing a single punch can change everything. Tate was never the same after that loss. Sugar Ray Leonard also defended his newly won welterweight title by KO over Davey Boy Green that night, his last fight before his big showdown with Roberto Duran.

Mike Weaver holds the distinction of having won the world heavyweight championship with the least amount of time remaining in the last round (v Tate), and losing it with the least amount of time elapsed in the first round (v Dokes).