Fight City Legends: King Of The Canebrakes

On this day way back in 1933, a young man, a boxer, lies close to death in a hospital bed in Macon, Georgia. The room is quiet, morose even, such a contrast to the thrill seeking, hundred-mile-an-hour life that the young pugilist had led. The dying man is a mere 28 years of age.

The physicians believe his ‘tremendous vitality’ is the only thing that keeps him from passing, but soon it is apparent that this won’t be enough. The young fighter cannot win this battle and he dies with his wife — a patient in the same hospital, having just given birth to their third son — at his bedside. His last words are, “I am going, old girl,” a final goodbye to his beloved.

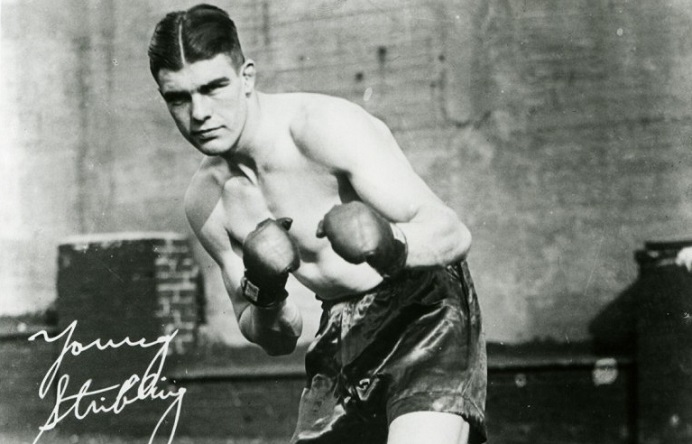

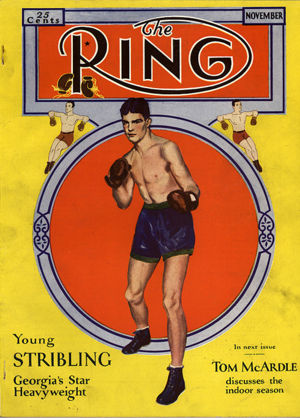

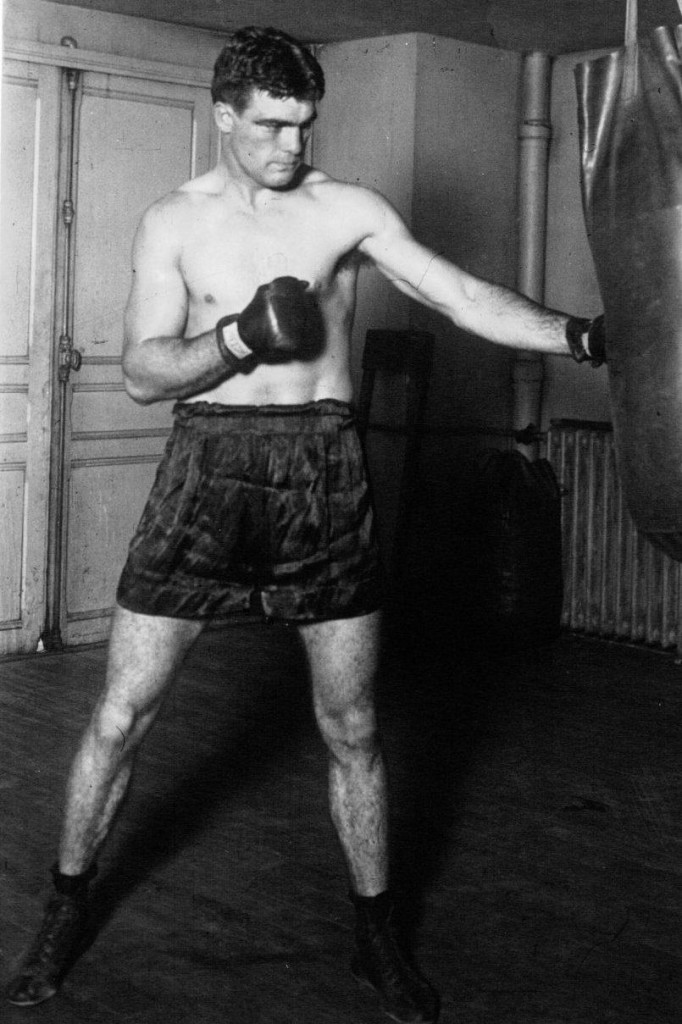

William Lawrence Stribling Jr,. or Young Stribling as he was known in the ring, lived his short life to the fullest. From fast cars, planes, speedboats and motorbikes, to taking on a plethora of the best middleweight, light heavyweight and heavyweight contenders the fight game had to offer, he lived fast and, sadly, died young.

Despite his young age, Stribling was a veteran of close to three hundred prizefights when he died. His fistic career began as a featherweight in 1921 when he was just 16-years-old, before be eventually moved up to the light-heavyweight and heavyweight divisions. He competed in various countries during his twelve year career, including Cuba, England, France, Australia and South Africa, and throughout the United States.

He was world titlist once, for a few hours at least. The year was 1923 and a then 17-year-old Young Stribling, astonishingly the holder of a 64-3-12 record, went into the ring in Columbus, Georgia to face the light heavyweight champion of the world, Mike McTigue. The bout was shrouded in controversy, the kind boxing knows only too well. The New York Times in fact reported that McTigue was forced to compete that night despite a broken thumb: “McTigue issued a statement declaring that he had been forced into the ring with a broken thumb at the point of pistols, and Joe Jacobs (McTigue’s manager) stated that spectators had threatened to hang him to a tree…”

The controversy continued after the final bell when referee Harry Ertle deemed the bout a draw, only to change his verdict to a victory for challenger Stribling. But the newly crowned champion would lose the title as quickly as he had gained it as Ertle later recanted the decision, as reported in The New York Times:

“Ertle declared the bout a draw at the end of the tenth and final round. The spectators closed in on the ring, demonstrating their disapproval. Ertle, after a conference with newspaper men, changed the decision and the match and the light heavyweight championship was awarded to the Macon high school boy, who had sat in tears in his corner during the excitement. Tonight, three hours after the fight, Ertle again spoke, this time declaring that his original decision, that the fight was a draw, was correct.”

Despite the defeat, Stribling continued to compete with a frequency unheard of in today’s fight game. He racked up victories over fighters both good and bad, including a rematch win over McTigue in March of 1924, a six round draw with future champion Paul Berlenbach, and a six round decision over future Hall of Famer Tommy Loughran at Yankee Stadium, a match appearing on the undercard of the Harry Greb vs Ted Moore fight and witnessed by some fifty thousand.

It was in 1925 when Stribling was dubbed ‘The King of the Canebrakes’, a moniker given to him by famed sportswriter of the times Damon Runyan, in reference to his popularity in rural areas. This popularity was far from unanimous though as Stribling was one of the many boxers of the time to draw the colour line, refusing to take on black challengers.

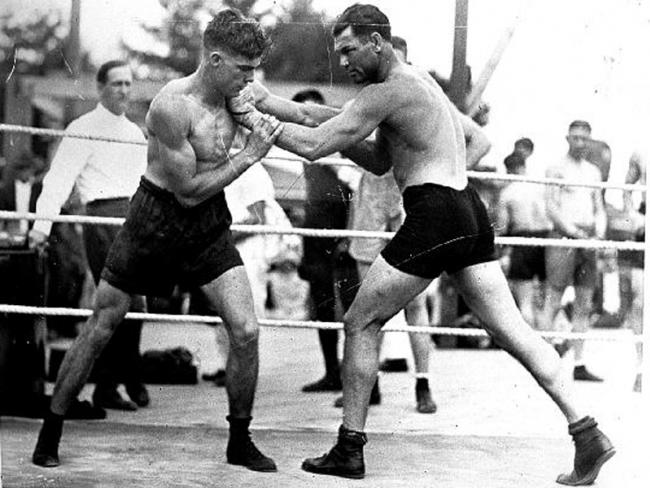

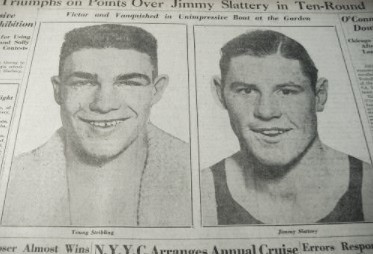

Many of the young Georgian’s fights were against lesser quality opposition but he was a fan favourite, if not for his performances, then for his bravado outside the ring. He wasn’t adverse to a publicity stunt and one of the more famous ones occurred when he flew a plane over New York City and circled the Empire State Building. Not all of Stribling’s opponents were pushovers though. He defeated Tommy Loughran for a second time in March of ’25, went 2-1 against Jimmy Delaney, beat Johnny Risko in July of that same year, and in 1926 went 1-1 with future Hall of Famer Jimmy Slattery.

The New York Times accredited Stribling’s victory over Slattery to his tricky style and superior strength: “Stribling was once an acrobat and the traces of that calling are still discernable in his work. He cannot be compared to Slattery as a boxer. But Stribling is strong, resourceful and tricky, and these were the elements which decided the battle in his favor. The Southern lad was stronger than his rival at all stages of the fight and at the final bell.”

Stribling fought another seven times in that first half of 1926, winning all before gaining a second chance for the light heavyweight title against new champion Paul Berlenbach. Berlenbach was a formidable puncher and had defended the title three times since he had defeated McTigue for the crown. The New York Times declared the fight a real pick ‘em match: “The betting odds, which earlier in the week were favoring Stribling at 7 to 5 and 6 to 5, continued to shorten yesterday, with even money finally prevailing.”

Stribling trained hard and came in at a slim 171 pounds while Belenbach weighed in at 174.5. The training methods employed by the challenger were questioned by the State Athletic Commission’s own doctor who declared that Stribling had “killed himself” to make 171 pounds.

The bout started well for Stribling and he took the opening two rounds but in the third stanza the champion began to find his mark and his brutal punching became the deciding factor, as The Times reported: “Berlenbach failed to score a knockout only because Stribling, hurt and stung early in the fray, forgot all about the boxing skill and tricks he has picked up in five years of steady fighting, and turned desperately to a strictly defensive fight. He broke and ran before the champion, clinched at every turn and hugged and mauled Berlenbach on the slightest provocation.”

The decision after fifteen rounds was a unanimous one and Stribling had once again fallen short of winning a world crown. But he fought on and returned to his winning ways, beating his next seventeen opponents, including the likes of Hall of Famers Battling Levinsky and Maxie Rosenbloom. Tommy Loughran was the man to halt the streak. In May of 1927 the light-heavyweight boxing master won a unanimous decision over Stribling at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn, New York.

But Stribling was now taking on much bigger men and it was paying dividends. The heavyweight scene had always been boxing’s jewel and with it came fame and fortune. Stribling and his manager, who happened to also be his father, initiated an audacious plan to seize the heavyweight championship of the world. After an eighteen month period in which Stribling fought 57 times and suffered no defeats, he became the number one contender as ranked by The Ring magazine.

Gene Tunney, the man who took the title from Jack Dempsey, had retired in July of 1928 and the search was on for a new champion. Promoter Tex Rickard set about staging a series of bouts to crown a new champion and Stribling was to play his part. At one point he had been matched to fight Tunney but the financial arrangements had fallen through, so upon hearing of Tunney’s retirement, Stribling’s father laid a claim to the title based on Stribling’s victory over Johnny Risko and the two wins against Australian heavyweight Gene Cook, who had twice beaten Tom Heeney.

In February of 1929, Young Stribling got his first real chance to prove he was indeed worthy of the title of heavyweight champion when he faced Jack Sharkey in a ten round bout in Florida. The match was to be the last organized by the larger than life Tex Rickard, who had died on January 6th of the same year. Some thirty-five thousand fans attended and the thunderous applause began even before the main event as the referee for the bout, Jack Dempsey, was introduced to the packed house.

The fight itself was a battle of youth vs experience, speed versus size, and on this occasion it was the experience and superior strength of Sharkey that shone through. Alan J. Gould of The Southeast Missourian summed it up: “In a ten round match that was alternately fast and dull, hard fought and close, but punctuated with few real moments of throbbing excitement, Sharkey overcame a big lead … and won with a strong finish through the last four rounds.”

The loss put Stribling out of the title picture but that didn’t stop him from frequenting the ring, fighting on with much success and for the remainder of 1929 and 1930 lost just two fights, both by disqualification. One of those occurred in November of 1930 against the mob-controlled behemoth, Primo Carnera. Stribling lost by disqualification but then won the rematch less than three weeks later in the same fashion. Both matches are thought to be fixed.

With wins over heavyweight contenders such as Otto von Porat, Phil Scott and Tuffy Griffiths, men all ranked in the top ten in 1929 and 1930, Stribling secured the biggest fight of his career, a shot at the heavyweight champion of the world, Max Schmeling. Stribling had his doubters and there were those who said he lacked the heart to compete with the better heavyweights, a view inspired by the safety-first approach on display in some of his higher profile bouts, but his second round knockout of Englishman Phil Scott convinced many he deserved a chance to face Schmeling.

The hype in the lead-up to the match was befitting that of a heavyweight championship bout and much of it surrounded the issue of Schmeling’s apparent refusal to rematch Jack Sharkey following the German having taken the vacant heavyweight crown by disqualification. Stribling then created a stir by flying his plane over the champion’s Pennsylvania training camp.

In a New York Times report on June 26, 1931, the challenger outlined his plan of attack: “For the first five rounds the lean, powerful Southerner will pile into Schmeling throwing every punch he has in an effort to win the title on a knockout. It will be a campaign of aggression, a charging attack built around left hooks to the body, left jabs to the head that Bill believes will prop the German up for the right-hand smashes to the chin which have foundered most of Stribling’s 127 knockout victims.”

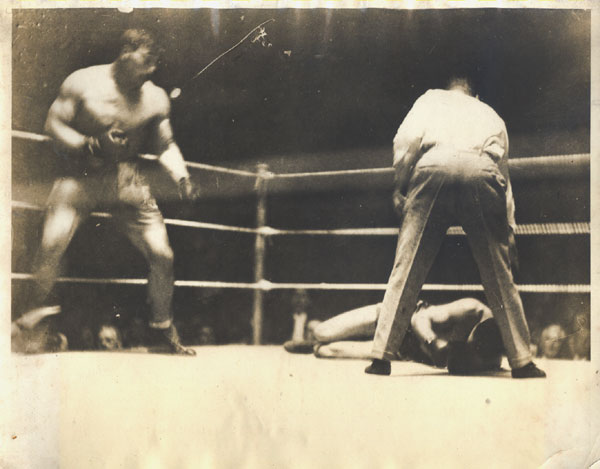

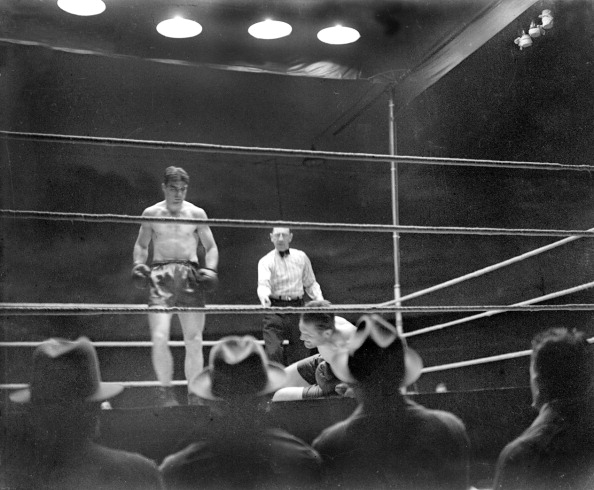

The plan started off well enough as Stribling took charge and threw all he had at the champion, but after four rounds it was clear Schmeling’s punch resistance was more than up to the task while his own blows were taking a toll on the challenger. Stribling was a broken man by the middle rounds and he fell back to old habits of clinching, mauling and running to avoid further punishment.

In the final round Schmeling dropped the challenger with a hard right to the jaw. Stribling was down for the count of nine but bravely fought on before Schmeling once again laid it on thick and, with just fourteen seconds left, referee George Blake stopped the bout to save the challenger from further punishment. The dream of becoming heavyweight champion, one that Stribling’s father had held dear ever since his son had been born, was shattered. Many suspected this was Stribling’s last shot at championship glory and they would be proved right.

Despite this huge setback, Stribling was back in the ring just three months later and went on to win three bouts in succession, looking impressive against less than stellar opposition. But it was clear his days as a top contender were at an end when he faced heavyweight Ernie Schaaf in February of 1932 and was badly beaten over ten rounds.

But Stribling fought on, competing in America, Canada, Australia, South Africa and France and losing just once, against European heavyweight champion Pierre Charles, via disqualification. His level of opposition was again questionable, but he did defeat the classy Australian Ambrose Palmer, albeit with a sixteen pound weight advantage. Stribling fought his final bout on September 22 in 1933 against Maxie Rosenbloom, winning a ten round decision against the future Hall of Famer.

A month later a tragic accident took the young fighter’s life. While driving his motorcycle to the hospital to be with his wife, Stribling waved to his friend, Roy Barrow, in a passing car and failed to see another car behind that of Barrow’s. The collision severed his left leg and crushed his pelvis, but amazingly Stribling had the presence of mind to demonstrate his quick wit to Barrow, the first to reach him, when he remarked: “Well kid, I guess this means more roadwork.”

Prominent sportswriter of the times, Paul Gallico, was always quick to criticize Stribling, once saying he “was afraid of nothing that rolled on wheels or flew on wings, but was a coward in the ring.” Such a statement is unduly harsh and unfair for a man who fought in almost three hundred bouts over just twelve years. Max Schmeling obviously thought otherwise. Three years after Stribling’s death, Schmeling ordered flowers to be left on the grave of the man he beat and the inscription on the card read, “In fond memory of days spent together – in loving friendship.” — Daniel Attias