Sept. 12, 1992: Chavez vs Camacho (Part II)

Click here to read part I of the tale of Chavez vs Camacho.

With a delirious crowd awaiting the opening bell, JCC walked through a mob from his dressing room to the ring while the Thomas and Mack Center blasted an especially campy pop song through the PA:

Pound for pound

Libra por libra

Julio Cesar Chavez

Un gran campeon

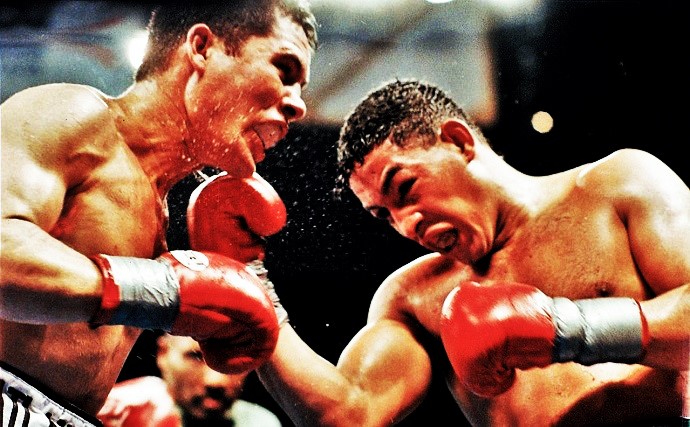

At the opening bell, Chavez, who possessed a reputation for being a slow starter, ran to Camacho and launched a wide left hook upstairs, looking to inflict damage from the get go. He then began peppering Camacho with strong lead right hands, sometimes even allowing himself to double them, just like he doubled the hooks, first to the head and then to the body, while evading Camacho’s timid jabs with upper body movement.

From very early on it was evident Camacho would have to spend all night picking his poison: if he tried to escape by moving towards Chavez’ right flank, he would meet one of those hard lead right hands face-on; if he instead tried Chavez’ left side, JCC made him pay for it by drilling a left hook to the body. Worryingly for the Boricua and his camp, Camacho was unable to pull the trigger on the backfoot: his punching volume was nowhere near the level it needed to be at to bother JCC, nevermind stealing rounds. He was equally unable to position himself into angles to score on Chavez while denying him an easy target. Meanwhile, the flurries and flashy combinations that swayed judges in his favor on past occasions were notably absent.

What the large majority of pundits had predicted the moment the fight had been signed was exactly what was happening inside the ring. Camacho was past it, Chavez was too good for him, and both truths combined to produce a one-sided beating. The largely pro-Chavez crowd couldn’t care less; they celebrated every clear punch from Chavez with the same intensity they booed every clinch from Camacho, which started coming hard and fast after the first three rounds.

The crowd’s chant of “Duro! Duro!”–Hard! Hard!–encouraged Chavez to keep up the pressure and to deny Camacho any breathing room, but it also celebrated the Mexican’s approach to fighting: the relentless pursuit, the merciless accuracy, the pummeling power. It was hard to find an exchange, never mind a round, that belonged to Camacho; in fact, if anything went the Puerto Rican’s way that night it happened in the fourth round, when he landed a roaring uppercut on Chavez’ famously imperturbable chin. While it temporarily shut up the public, Chavez took it with characteristic equanimity, his stoicism crushing any fantasies Camacho might have had of following up.

As the rounds went by, JCC’s body blows robbed Camacho’s legs of their energy, rendering the beating more pronounced. The Boricua went into survival mode–albeit progressing through different iterations–from as early as round four. Whatever credit is usually awarded to Camacho for this fight centers on his “taking his beating like a man.” Fair enough: for all the hard shots Camacho absorbed, he never wobbled or came close to hitting the canvas. Regardless, both “Macho” and his corner realized beyond any doubt he was neck deep in it sometime after the middle rounds. During the one-minute break between the eighth and the ninth, with Camacho’s left eye half shut due to the swelling produced by Chavez’ pinpoint lead rights, the Puerto Rican’s corner found itself unable to offer any kind of tactical advice, merely exhorting their man to “throw something, anything!”

Camacho duly responded, turning the ninth into the most action-packed of the night by far. Having sensed Camacho’s decline, Chavez ramped up the intensity of his attack, while the Puerto Rican fought back as best he could, matching the champion at least in volume if not in effectiveness. This is not to say that Camacho came close to troubling Chavez, that he ignited a late rally, or that he even won the round, but it showed that under tremendous pressure and on the brightest stage, Camacho’s dignity and valor as a fighter rose to withstand Chavez’ furious charge.

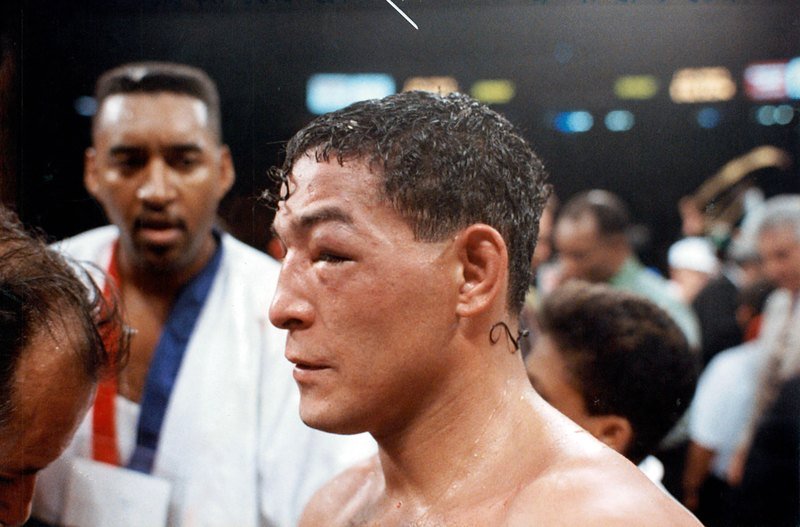

After the final bell no one needed to hear the scorecards to know the outcome. Camacho’s face told the whole story of the fight: his half-shut left eye spoke of the dozens of lead right hands Chavez had drilled into his orbital bone, just as the cut over his right eye spoke of the accuracy of JCC’s left hooks. The post-fight interviews saw Chavez declare: “Camacho turned out to be a better fighter than I thought. He’s not the maricon I thought he was.” At that moment, Camacho crashed the interview, coming into frame while shouting, “Macho time! Macho time!”

All the enmity and hard feelings that had been hyped ad nauseam pre-fight had dissipated into the dry desert air as if by magic. Chavez promptly put his arm around Camacho’s shoulders, the couple turning into best buds stumbling out of their favorite watering hole. Chavez continued: “I thought I could’ve knocked him out, but Macho was able to take a lot of punches. On top of that, my right hand wasn’t responding well.” At that point, Chavez was handed a bottle of water to sip on while Camacho picked up the conversation; Chavez then put the bottle to Camacho’s mouth, letting him finish it. Still on air, both agreed that a rematch was in order.

Coincidentally, a rematch of Chavez vs Camacho was the only thing less necessary than the reading of their scorecards. But can anyone blame them for pitching it? The event was a financial bonanza for everyone involved: the bitter rivals turned best amigos earned $3 million a piece for the fight–notable amounts for sub-welterweights at the time. Meanwhile, King raked in over four and a half million dollars at the box office; one of the highest grossing gates up to that point for a fight below 147-pounds. The pay-per-view and closed circuit sales around the world would boost everyone’s revenue even further. Moreover, both Chavez and Camacho’s name recognition went straight through the roof following their encounter. While fashion brands courted Camacho to design and model for them, Chavez’s first stop upon his return to Mexico was Los Pinos, the presidential residence in Mexico City, where his friend Carlos Salinas awaited to congratulate him.

A more lasting impact from the fight was that in conquering Vegas, Chavez and King had laid out the blueprint that would be faithfully followed for decades to come by the sport’s biggest stars. Oscar de la Hoya, Floyd Mayweather Jr, Manny Pacquiao and Canelo Alvarez all made and continue to make millions upon millions by fighting on Mexican holidays in Las Vegas. Chavez himself continued to profit handsomely from the arrangement for years thereafter, putting an end to the parking lot boxing promotions that prevailed in Sin City throughout the 80s, and cementing the reputation of the Thomas and Mack Center and later the MGM Grand Garden Arena as the boxing venues in Vegas. On January 29, 1994, Chavez starred in the first boxing card to be staged at the newly opened MGM Grand, then the largest hotel in the world. According to Lang, “The unfoldment of boxing at the MGM Grand Garden was the most significant boxing-related development in Las Vegas during the period when Mike Tyson was locked away in prison.” Yet one more entry in Chavez’ already outstanding legacy.

For all that, it can be argued that Chavez vs Camacho represents the highest high in JCC’s career, his peak in every category that matters to a prizefighter: ring prowess, popularity, and drawing power. While Chavez had already achieved notoriety and wealth beyond those available to the large majority of fighters, the victory over Camacho cemented them beyond any doubt. Significantly, the Puerto Rican’s scalp was the last great trophy JCC ever added to his case. Running up his ledger to 107-6-2 before retiring in 2005, Chavez would still go on to star in big fights against Pernell Whitaker and Oscar de la Hoya, but would fail to earn any more significant wins, the exception being, perhaps, Frankie Randall in their rematch.

Without a doubt, in 1992 Chavez was on top of the world. In an interview years later, Chavez would acknowledge as much: “[After Camacho] I couldn’t even go out on the street anymore. It was incredible. People were going crazy. All they did was rain acclaim and compliments on me.” Ponce provided further insights: “Following his win over Camacho, Chavez claimed access to a summit so high that it can only be reached with the help of a relentless hype machine, and of course, by possessing fighting qualities rarely seen in the world of boxing. King had at long last achieved his goal: to awaken the public to what Chavez himself–despite his splendid resume–hadn’t been able to. Namely, that he was a true idol, worthy of being the focus of massive, nationwide recognition… JC’s explosive presence in the ring, coupled with Don King’s publicity and promotional magic, allowed Chavez to sport an impeccable halo, despite any flaws he may have had as a person.”

Unfortunately for El Gran Campeon Mexicano, things could only go downhill from here, and his “flaws as a person” were about to become painfully public. What awaited JCC on the other side of the Camacho fight was a long climb down the summit he had just conquered. A nasty divorce which included a domestic assault lawsuit, a custody battle for his three kids, multi-million dollar tax evasion problems, increased scrutiny due to his closeness to members of narco-cartels in his beloved Sinaloa, and alcohol and drug abuse problems were all in the offing for the idol. Years later, Chavez would admit: “Unfortunately, my descent followed [the Camacho fight.] I began to abuse alcohol and drugs; I kept on winning, but it wasn’t the same. My addictions grew and then the defeats came along, because I began disrespecting the sport of boxing.”

As if mirroring the behaviour of his newly made friend, Macho Camacho also began having more run ins with the law following the Chavez fight. These were due not only to his love for speed, but also his abuse of recreational drugs. Being at the wrong place at the wrong time became a way for Camacho to continue making headlines when away from the ring. Regardless, in the mid 90s, he ramped up his ring appearances, fighting as many as six times in 1996, mostly against obscure opposition. However, his name remained a hot enough asset throughout the decade that he was able to cash in by facing names like Felix Trinidad, Oscar de la Hoya, and even Sugar Ray Leonard and Roberto Duran in increasingly cringeworthy spectacles. After fighting for the last time in 2010, Camacho’s troubled life became the main way in which he continued to get attention; his file saw the addition of domestic and child abuse charges in early 2012. Later that year, Camacho died in a car shooting incident where drugs also played a role: an ignominious end to the tumultuous life of one of Puerto Rico’s most renowned boxing heroes.

Despite Chavez and Camacho being positioned as opposites in order to hype their fight, their lives and personalities shared plenty of commonalities, whether they realized it or not. Perhaps JCC’s and Macho’s chumminess after their encounter in 1992 was just a case of two prizefighters preparing themselves to enjoy their newly earned bounty. But what if there’s another explanation for their sudden closeness? More than merely an entree for a bloodthirsty audience, Chavez vs Camacho might have served an altogether different purpose: a laying-on of hands ceremony in which by some mysterious, ineffable way, they came to recognize in each other a piece of themselves.

Namely, that both of them at an age when they had barely begun to comprehend who they were and where they came from, in an act of defiance to the obscurity and poverty which engendered them, joined a cruel trade that eats up and spits out young men on a daily basis. Namely, that instead of being thrown to that fate, it was the caprice of the boxing gods to reward them with riches and recognition, to thrust them to the top of the sport’s food chain, with all the pressure and temptations that come with it. As much as Chavez was presented and perceived as a boxing idol and role model, he struggled with substance abuse, sketchy friendships and violence in his personal life as much as Camacho did. The Puerto Rican, tragically, ended up losing his battle with that part of his life, while JCC emerged from it to regain a measure of health, and to a stable life as a boxing broadcaster for Mexican media.

As a boxing match, Camacho vs Chavez seemed at the time it was staged a story with an already known outcome. Nevertheless, its success as an event was evidence that the Mexican and the Puerto Rican had mastered the command of the forces that rule modern prizefighting: turning mercenary combat into entertainment and distilling violence into fan-approved plot-lines, while keeping money as both driver and reward. But beneath the surface, well beyond the reach of the bright Las Vegas lights, lies a question that pulsates with as much vitality today as it ever did. After the roar of the crowd had long faded, after their once bursting coffers had been drained to a void, after they had been unseated from their spots at the top of the boxing food chain by younger talents, their own idiosyncrasies, and by time itself — why did such vastly different outcomes await Julio Cesar Chavez and Hector Camacho? Yet one more entry in boxing’s ever growing list of unanswerable questions. –Rafael Garcia