I Fight For A Living

One of boxing’s most enduring tropes is that of the prizefighter who punches his way out of poverty and into a life of riches and success. Throughout the fight game’s long history, countless pugilists have lived that cliché, to the point that those of us who follow the sport as spectators, by virtue of overexposure, risk becoming desensitized to just how much effort it takes—and how many setbacks have to be overcome—by those who succeed in such a quest. It bears reminding that, even when realized, the cliché itself is, very often, only half the story.

Louis Moore’s I Fight for a Living: Boxing and the Battle for Black Manhood is the perfect corrective against that risk, a helpful reminder of the extreme hardships so many prizefighters have had to endure. In his meticulously researched book, Moore presents a lively portrait of the boxing landscape at the turn of the twentieth century, but more than that, he successfully places black prizefighters in their proper socio-cultural context. To do this, he takes a close look at the conditions under which the most famed and skilled black boxers entered the world of pugilism, and how they achieved success in the ring, despite the extreme racism which afflicted both pugilism and society in general.

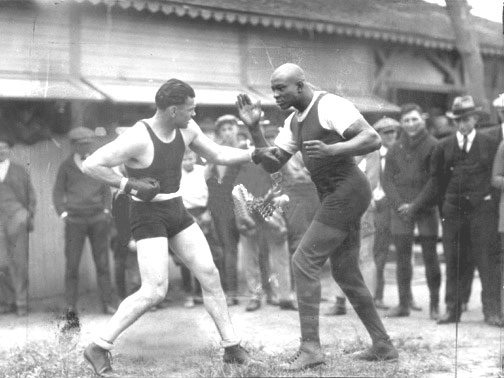

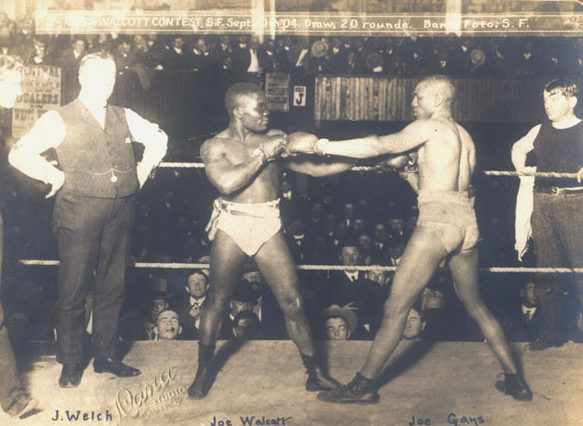

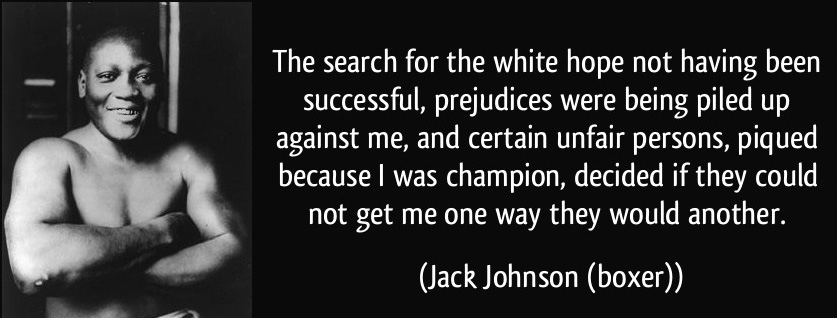

Moore mixes historical sources–such as fight recaps, interviews, editorials, and news clippings published from daily newspapers–with assessments by various historians, including those specializing in boxing. At times, this approach gives I Fight for a Living the feel of an oral history, rendering vivid the life and times of such fighters as George Godfrey, Peter Jackson, Jack Johnson, Sam McVea, Joe Gans, and Sam Langford, to name just a few.

What boxing represented to all those fighters–and to many more whose names were not destined for long-term remembrance–was, first and foremost, a way to earn a living. This is not surprising considering the restricted options available for black men searching for a way to survive in post-Civil War America. Racism, much of it institutionalized, prevented blacks from climbing up the social ladder, if they were allowed to place their hands on it at all.

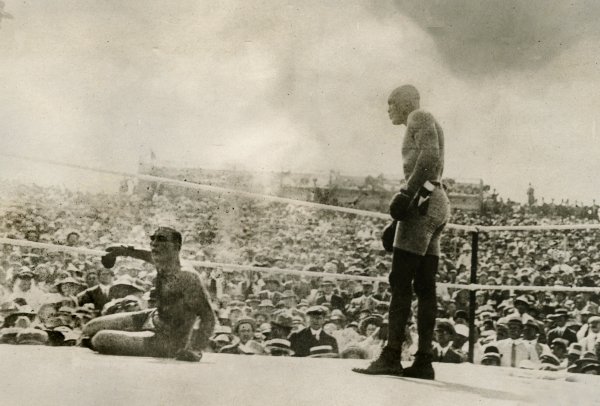

But prizefighting found itself in hot demand. This created an opportunity for young black men to prove their fistic worth inside a ring and be rewarded for it. It’s a bittersweet irony that the matches most in demand at the time–the ones that garnered the largest purses for both white and black fighters–were interracial fights. This is because the richest audiences for prizefights were composed of white men, and their top priority when attending a boxing card was to see a white fighter defeat a black one, thus confirming their conviction in the supposed superiority of their race.

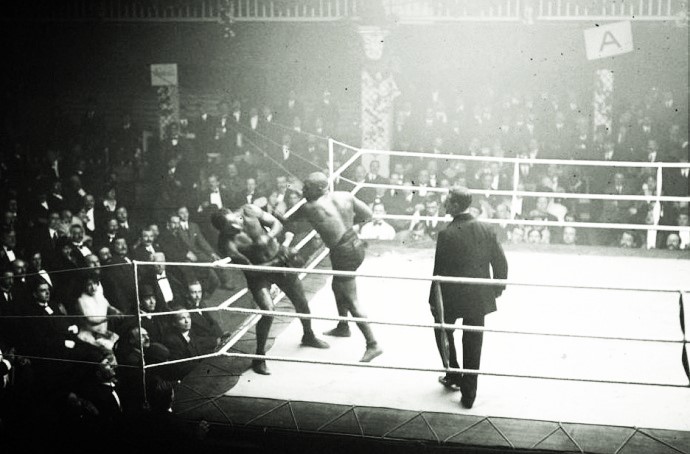

This is the reason fight promoters of the time often preceded a main event in which it was anticipated a white fighter might lose to a black boxer with the degrading spectacle of a “battle royale,” a bizarre free-for-all where several blindfolded black fighters were set loose in the ring to pummel each other until only one was left standing. If the idea of such a spectacle disgusts us today, we can take solace from what transpired after it was over, the moment when the two main event fighters entered the ring and a black fighter achieved something resembling full equality, having at last been granted the opportunity to stand face-to-face with a white fighter before, more often than not, and as Moore documents repeatedly, securing victory.

But another element of the inherent unfairness of this enterprise was the fact that to secure their chance at the largest paydays granted for facing white fighters, black boxers had to first hone their skills against all the other top black opponents who were also waiting in line. “Colored championships” were thus created with the specific goal of finding the best black fighters at the different weight classes. Thus, the public could more clearly identify who the white “world” champion was avoiding and then determine which black fighter most deserved a shot at the champion, in case the latter ever decided to grant such an opportunity.

This resulted in top black pugilists of the time battling each other again and again, sharpening their skills and punishing their bodies for peanuts, always aware that a bad outing or a tough loss could send them all the way to the back of the queue. Meanwhile, the white champion disposed of lesser competition for easy paychecks, while at the same time asserting white dominance over blacks by denying them the opportunity to compete for the supposedly legitimate world championship.

White belt-holders may have been reluctant to trade blows with black challengers, but that did not deter black fighters from competing and, indeed, the sheer number of opportunities available to them to fight was remarkable, suggesting that, despite everything, their talents were in high demand. Boxing fans of the time appeared to have a kind of love-hate relationship with black fighters; on the one hand they admired their skills, fighting acumen and even their chiseled physiques, but on the other hand they could not bear to see them defeat white boxers, turning on them the moment they did.

Meanwhile, the white media often alternated between portraying black fighters as submissive, carefree Sambo caricatures, or denying them their humanity as a result of their triumphs, assigning their ring superiority to savage, animalistic characteristics. It’s a point that Moore documents extensively, by quoting plenty of dailies from the times and by reprinting some of the appalling newspaper cartoons that were standard fare at the time.

And then there were the conflicts between black fighters and the different factions within black society. While black elites didn’t care much for prizefighting in principle, they couldn’t help but latch on to the success of triumphant black prizefighters and attempt to make a role model out of such figures, only to drop them the instant their conduct outside the ring didn’t conform to their standards.

As for the lower black classes, they expected their ring idols to live the life of a good fellow, spending money left and right, gambling, partying it up, and signaling their success through flashy clothes and possessions. Tellingly, the dichotomy between becoming a role-model or living it up in the fast lane has followed black athletes well into the 21st century and Moore explores this concept in great depth in his book.

But perhaps the chief strength of I Fight for a Living, at least for fight fans, lies in the way it fills in the holes of the boxing history most of us are familiar with from that era, which usually revolves around the lineage of the crowns. As Moore makes abundantly clear, the black-dominated periphery of the title picture is a rich source of compelling material, both for historians and for those who just want to hear a good boxing story.

While there are plenty of detailed vignettes in this book on the most popular fighters of the time, each documenting their upbringings, personalities, and the trajectory of their careers, not to mention how they made and spent their fortunes during and after their heyday, there’s also plenty of good, old-fashioned ring reportage. In this respect, the astonishing tale of how Morris Grant–then colored champion of New York–and Connecticut’s Charles Hadley, aka “The Professor,”–met in 1882 in the last of their twelve encounters to determine who was the colored heavyweight champion, stands out in particular:

“When the bell sounded… Hadley rushed at his man, hitting left and right, and driving Grant all over the stage, pounding and thumping him with no intervals until Grant fell all in a heap on the floor. In the second round, Hadley continued his furious fighting and knocked Grant out of the ring. [Then] Hadley dropped him three more times. Grant’s corner man, Charles Cooley, tried to stop the fight by sitting Grant on his stool, but the crowd wanted more action and yelled at Hadley to “give it to him.” The Professor obliged. But before Hadley could finish Grant, Grant fell off his stool to avoid the knockout. Referee Harry Hill declared Hadley the winner… After the fight Cooley stood in the center of the ring and yelled “I can lick any 180 pound nigger in the world for $500.” The Professor coolly walked over to his adversary and decked him. Cooley got up, and Hadley knocked him down again. During the ruckus somebody handed Cooley a revolver; fortunately, before Cooley could shoot, the police grabbed him and threw him out …”

It’s enough to make any present-day boxing controversy, even Mike Tyson’s ear-biting episode, look like something from Sesame Street, but it also serves as a reminder of prizefighting’s troubled nature and history. Moreover, it illustrates the lengths black fighters were willing to go, and the risks they were willing to take, to make a name for themselves in such a turbulent and risky enterprise. In a time when securing big fights, ie. interracial fights, was a perennial problem, the greatest asset of black fighters became their reputation.

The fact so many of them toiled under abhorrent racism and unfair treatment from their fellow sportsmen, from the media, from society, and from their own governments, attests to their incredible fortitude. The fact so many of them engraved their names in golden letters in the pages of boxing’s history books, attests to their undeniable excellence. I Fight for a Living is a fitting remembrance of all of them, and–in a time when hatred and bigotry seem to be gaining ground against decency in so many parts of the world–a timely reminder of the darkness and ugliness into which such ideas and behavior can lead us.

–Rafael Garcia