Dark Trade

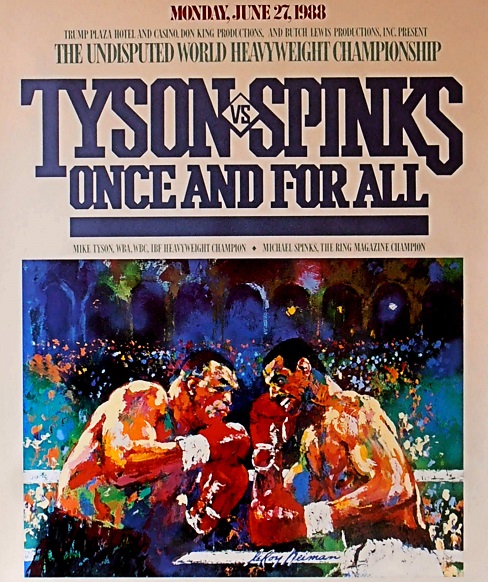

My earliest memory of boxing is a poster for Mike Tyson vs Michael Spinks from back in 1988, the big heavyweight superfight that lasted exactly 91 seconds. The poster was on the wall of a restaurant and the paper looked worn; maybe that was the aesthetic, or maybe it had been outside in the spring rains. I was eight years old, so of course whatever recollection I have of that poster and of Tyson is certainly romanticized. I was old enough to be enamored by the dominance of the “Baddest Man On The Planet,” but too young to see the darkness swirling around him, a darkness inherent to boxing itself.

A few years after that brief but violent clash, journalist Donald McRae set out on a journey to explore boxing, the sport with which he’d been enamored since his childhood in South Africa. It began in 1991 with McRae talking to “Iron” Mike himself, just before his rematch with Razor Ruddock, a fight that would be Tyson’s last before going to prison. And in the first pages of his book McRae captures both the overcast on the horizon of every boxer’s life, along with the redeeming qualities in the storm’s shadow. Many more interviews followed and the eventual result was Dark Trade: Lost in Boxing, a deep and fascinating dive into the multifaceted humanity of pugilism. And because it starts with Tyson, I was in from chapter one; the book let me juxtapose my childhood memories of a sporting idol with the tumult I now know was inherent to his life.

Dark Trade was originally published in 1996 and became an influential part of the boxing canon, winning the William Hill Sports Book of the Year prize. The newest edition, from Hamilcar Publications, is the first published in the USA, and the stories and personalities do take on some new meaning some twenty-five years later. But great fight writing, like all great literature, does not diminish in value as it ages; it appreciates. Especially when the focus is on the deeper dynamics at play. McRae can break down a fight with the best of them, but that’s not the conceit of this volume. His focus is always on the people, and through the book we see his relationships, and sometimes friendships, develop with the fighters and those around them.

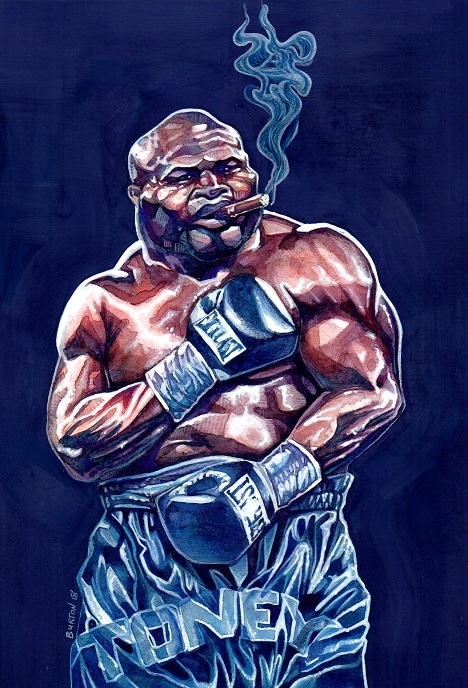

It’s fitting that the cover of this edition features a memorable painting of James Toney by Amanda Kelley, because it is “Lights Out” who McRae examines more closely than any other fighter and who the reader comes closest to. McRae became friends both with Toney and the fighter’s mother, Sherry, and stayed in close contact with them through the most tumultuous portion of Toney’s career. As such, we get a close and detailed look at what boxing can do to a fighter in the pages about Toney. The chapters on the lead-up to his bout with Roy Jones Jr. and its aftermath, which also detail Toney’s vicious split with manager Jackie Kallen, are particularly insightful:

[Toney’s] cool bravado between the ropes sharpened his crude image on the outside. But there was hurt that went deeper than the scowling and the swearing. Since losing to Jones and then Montell Griffin, his trouble could be charted in the bulging contours of his thickening body. Problem multiplied on problem and it seemed as if he put on another fleshy handful of pounds every time something else went wrong in his life.

The explorations of Toney’s fall-out, and the even more harrowing stories of Gerald McClellan and Michael Watson, who suffered terrible brain injuries in the ring, show that this book does not shy away from the worst parts of boxing, but McRae does not wallow in the negative. One of my main takeaways from Dark Trade is not so much about the bleakness and pain of the fight game, but more about how McRae reveals the underlying human drama and the multifaceted nature of prizefighters. In talking about his admiration for boxers, he writes: “Much of that esteem stemmed from their bravery and intensity, but it was an essential vulnerability beneath those hard layers of machismo that moved me the most.”

That vulnerability does come out in the passages involving Toney, especially as McRae looks at the boxer’s relationship with his mother. But it also appears in interviews with Oscar De La Hoya, the pugilistic champion who often talks about his desire to be an architect, which was his mother’s backup plan for him had boxing not worked out. And, of course, there’s an extreme vulnerability with Tyson due to his tumultuous childhood and his experiences in prison, all of which McRae addresses with journalistic rigor combined with a healthy sense of empathy.

For a reader in 2019, particularly an American one, some of what McRae discussed back in the 90s seems prescient. A white South African, McRae is always conscious of race as he talks to black and Latin boxers throughout the book. Given the frequent and intense racial discussions currently going on in America, I found it interesting to look back on how the issues manifested almost a quarter century ago. He touches on De La Hoya not having enough machismo to be embraced by the Latin American community, issues regarding African Americans and the criminal justice system and, something at the forefront of race relations now, how Middle Easterners are perceived in a mostly white society. Of Naseem Hamed McRae writes:

“But when more than three-quarters of a packed 16,000 crowd at Cardiff Arms Park screamed the same word with the same mock religious frenzy, it was hard not to assume a disgust in every disgusted ‘Hamed, Hamed,’ to think every grating ‘who the fuck is Hamed?’ query was bound up in hatred of his perceived foreignness, his difference from a white Welsh crowd.”

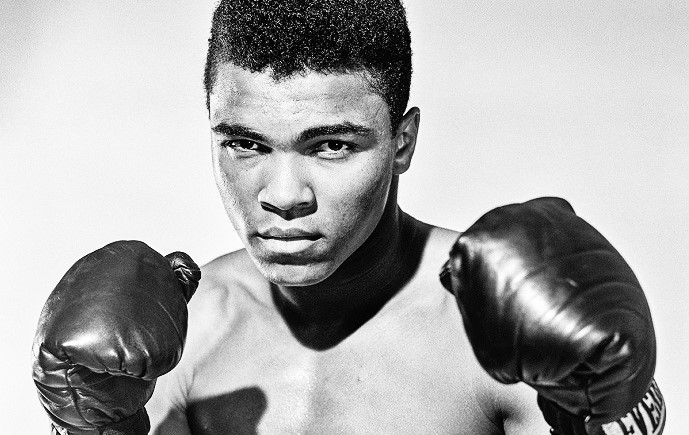

McRae’s sensitivity to race stems from his youth and personal experiences in apartheid South Africa, and he’s never shy about sharing what happened to him and how it shaped his relationship with boxing. That his first favourite boxer, like so many of his generation, was Muhammad Ali also plays a role. Decades on, McRae’s book proves to be ahead of its time in the way it addresses race with confidence and humility.

One aspect that left me wanting a bit was the new material in this edition. It isn’t of a lower quality by any means, but compared to the thoroughness of the original it can feel a bit cut off. McRae does follow up with Toney, Tyson, and Eubank, which helps to finish the stories which of course continued after the book’s original release, but he also mentions his experiences with several recent fighters, like Carl Frampton. However, he does not reach the same depth of insight as he did with so many boxers in the 90s, which makes the new chapter, while interesting for any fight fan, a little incongruous.

For example, we get a wonderful look at the hours immediately preceding Frampton’s first fight with Leo Santa Cruz (in my opinion, one of the more under appreciated fights of the last few years), but the interaction stops there. Of course, this is understandable; the only way to achieve the same depth would be to write a sequel wherein McRae follows a new generation of fighters for five or so years, and that’s a bit much for even the most ardent fan to ask. In any case, the earlier work stands on its own and the new chapter is just an extra bonus to an already excellent volume.

No follower of boxing is unaware of the darkness associated with the sport, but the complexities around it and the motivations of the pugilists, have no end in variation. This deeper understanding of everything that surrounds the fight game is what makes Dark Trade so compelling and why McRae’s brave book remains essential reading for any boxing fan. — Joshua Isard