Nov. 26, 1914: Langford vs Wills II

The first two decades of the twentieth century were a time of rapid evolution for the sport of boxing. Legal restrictions were being lifted around the world, and pugilism was rapidly shifting from an underground and shambolic enterprise, to something more organized and mainstream. Regulations standardized, techniques evolved, and the skill sets of elite fighters became more sophisticated.

At the highest levels, world-class fighters competed at least a dozen times a year, sometimes more than twice that. Frequent action forced boxers to remain in shape year-round and to hone the skills that only constant training could provide. Competition was fierce, and every division was stacked with talent.

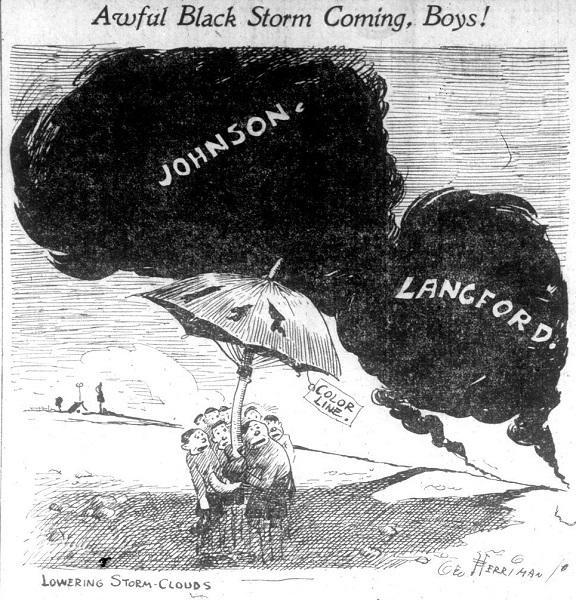

Unlike most other professional sports of that time, boxing, at least ostensibly, was racially integrated, but many white fighters refused to face non-white opponents, while many venues barred integrated matches, thus a great number of talented fighters were unfairly locked out from title contention. In 1908, Jack Johnson finally broke through, capturing the heavyweight title from Tommy Burns. But after becoming champion, he continued to reinforce the color line, defending exclusively against white contenders until in 1913, near the end of his reign, he drew against Battling Jim Johnson in Paris.

And so, during Johnson’s time at the top, talented black heavyweights plied their trade but never competed for the world championship, instead facing off against each other numerous times and largely dominating every other contender willing to take them on. Sam McVea and Joe Jeannette were two dangerous talents who would have been successful in almost any subsequent era. Incidentally, it was Jeannette who later openly criticized Johnson, stating that, “Jack forgot about his old friends after he became champion and drew the color line against his own people.”

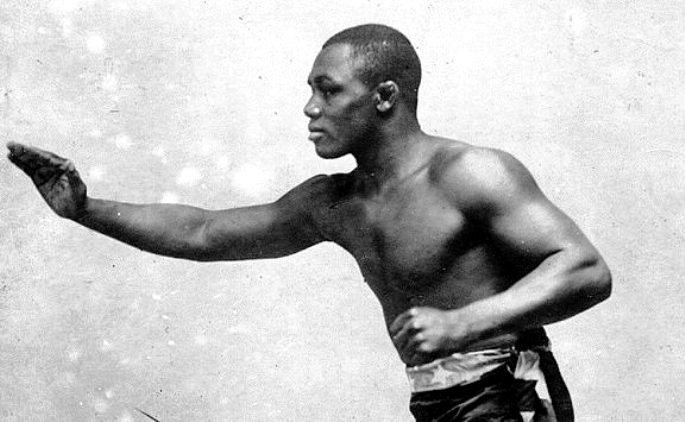

But even more dangerous than Jeannette and McVea was the great Sam Langford, a 5’7″ fireplug who fought for the world welterweight title in 1904, and carried his power up through the ranks to heavyweight, where he routinely knocked silly men much bigger than himself, that is, when he wasn’t boxing their ears off. During his prime, Langford’s power and ring skills, including clever footwork, fast hands, and potent combination punching, were virtually unequaled.

By 1914, Sam had been the top heavyweight contender for some time, not to mention the holder of the unofficial “Colored World Heavyweight Championship,” a sort of consolation prize for not getting a shot at the real title. Despite many public challenges, Sam just could not convince Jack Johnson to face him. It should be noted that a Johnson vs Langford duel did take place prior to “The Galveston Giant” winning the world title, a fifteen round match in 1906 which Johnson, enjoying a thirty pound weight advantage, won with little difficulty. But Jack was not inclined to give Langford a rematch; the fact he later declared Sam to be “the toughest little son-of-a-bitch that ever lived” gives us a clue as to why.

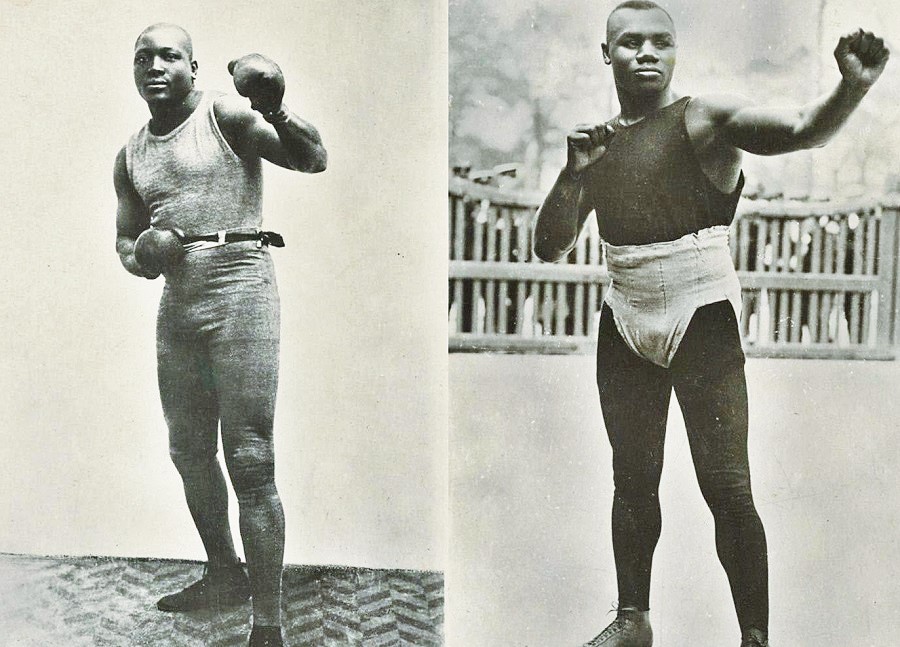

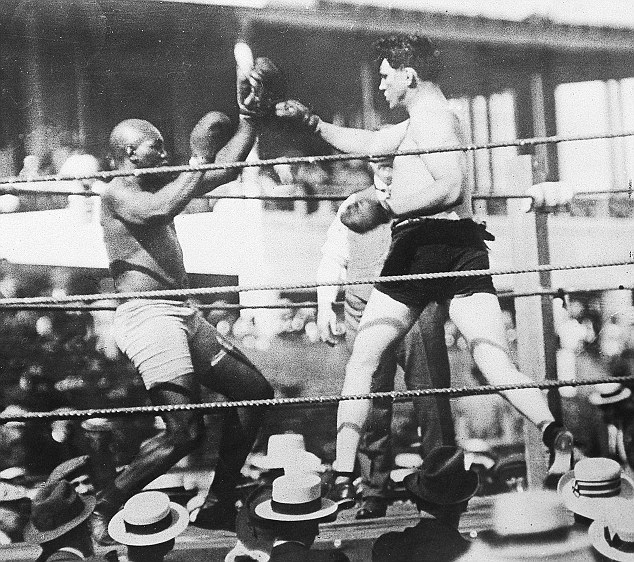

In May of 1914, Langford fought to a newspaper draw against an up-and-coming young contender from New Orleans named Harry Wills, with some correspondents scoring the match for the younger man. Wills stood just over 6’2″ and weighed around 210, making him one of the larger contenders of the day. At the time he had only seventeen pro matches on his record, but he still managed to more than hold his own against the highly regarded Langford. Little did anyone know, but that was only the first of many times “Langford vs Wills” would be at the top of a fight card.

By November, Wills had emerged as a serious contender, one that even Jack Johnson had to take notice of. “The Black Panther” followed his draw against Langford with another draw, one that many thought he deserved to win, this time against the great Joe Jeannette, before racking up eight straight victories through October. And so the time was right for another showdown with “The Boston Bonecrusher.” If Johnson wouldn’t give Langford a rematch, Sam was happy to oblige Harry and thus Langford vs Wills II for the World Colored Heavyweight Championship was set for Vernon, California.

By this point, the 31-year-old Langford boasted a record of 109-10-29 with 65 knockouts, having faced and defeated nearly every formidable challenger from welterweight on up. There was no style he hadn’t seen, no challenge he hadn’t surmounted. But the young contender from Louisiana still enjoyed those significant advantages in age, size, strength, and maybe even power. And while he lacked the skills of his more experienced foe, he was growing into a fine boxer in his own right.

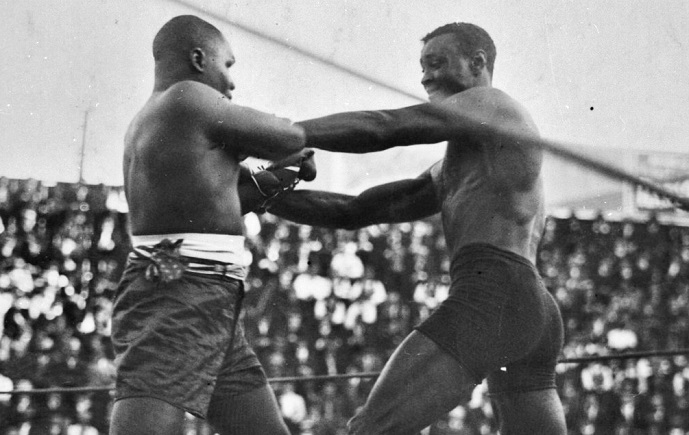

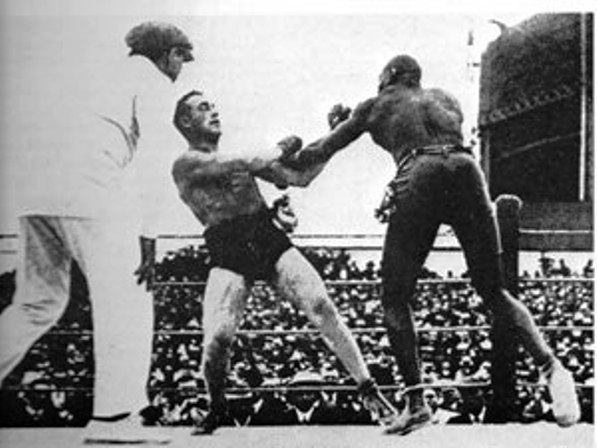

And so, in front of a large crowd, Wills sought to impose those advantages as quickly as possible, taking the fight to the older and smaller man and dominating him, dropping Sam four times in the first two rounds. At some point during the one-sided action Langford hurt his ankle, which hobbled him through the first half of the match.

But “The Boston Tar Baby” was nothing if not resilient and he rebounded to score a knockdown of his own, the match settling into a brutal battle of attrition. Straight punches from the long arms of “The Black Panther” made closing the gap difficult for Langford, but as the struggle entered the twelfth round he found his ankle loosening up and his footwork and balance improving as a result. The next two rounds belonged to Langford as he outmaneuvered and battered the larger man with heavy shots.

Reports of the manner in which Langford vs Wills II violently ended in round fourteen are somewhat conflicted. An account in The Indianapolis Star states that Sam continued wearing Wills down until a combination, punctuated by a left hook, dropped Harry for the count. However, in a 1953 interview, Wills himself would claim to have been in control of the round, backing his foe into a corner, when the hook arrived and turned his day into night.

Either way, what is clear is that Wills was ahead on the scorecards of the scheduled twenty round bout, and Langford pulled a victory out of the jaws of defeat with his power, tenacity, and strategic mind. An editorial from The Los Angeles Herald the following day argued that Wills was too green for such a monumental challenge, though Langford’s damaged eye and ankle might have begged to differ, not to mention the fact Wills had scored more than one knockdown on the great “Boston Terror.”

Soon after Sam was briefly given consideration as an opponent for the world title, but the match never happened and then Jack Johnson’s championship reign came to an end in April, 1915 when he fell to Jess Willard in Cuba. In the same month, Langford lost his “Colored” title claim to Joe Jeannette, and while he remained a formidable challenge for any boxer, his prime had passed. Amazingly, he would fight on for another full decade. Reportedly, Jack Dempsey did all he could to avoid facing Langford, and years later he candidly stated that he was “afraid” of Sam and that, had they fought, Langford “probably would have knocked me out.”

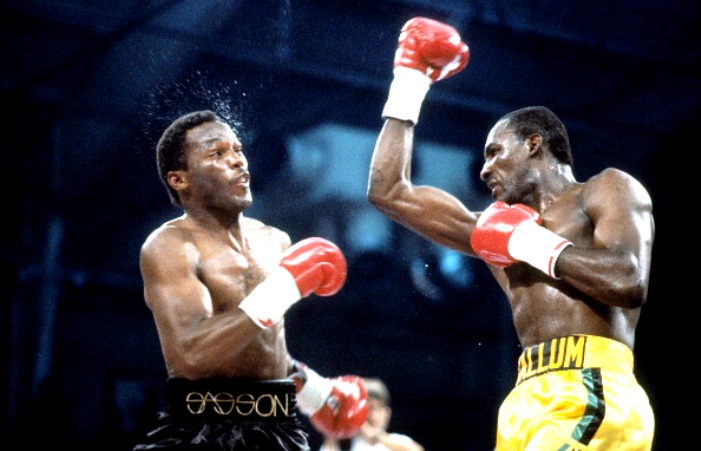

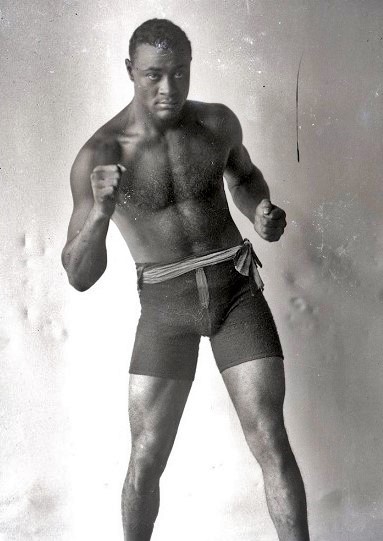

For his part, Wills continued to improve. He lost for the final time to Langford in February of 1916, but from that setback until October 1926, he compiled an incredible record of 58-2-3 with 34 knockouts, the two defeats being a fluke injury stoppage and a disqualification that was re-matched four days later. That ten year run included eleven victories over Langford, as well as wins against an all-star roster of heavyweight talent, including Sam McVea, Denver Ed Martin, Jeff Clark, Fred Fulton, Gunboat Smith, Kid Norfolk, Luis Firpo, and Charley Weinert.

During this time, Wills was arguably the best heavyweight in the world and a showdown with heavyweight king Dempsey was discussed and considered on numerous occasions but never came to pass. Based on his performances during his prime, one can argue that “The Black Panther” might have reigned as heavyweight champion for many years had the chance arisen. Alas, Harry Wills will instead be remembered, alongside his greatest rival, Sam Langford, as one of the finest fighters in all of boxing history to never win a world title. — Hunter Breckenridge