Shadow Box

Even if it had nothing else going for it—something very far from the truth— Shadow Box by George Plimpton will forever remain a bastion of boxing literature because of the image it contains of the “Near Room,” a place of dreadful foreboding which Muhammad Ali once described to the famed editor and journalist in striking, chilling detail:

“…a place to which, when he got in trouble in the ring, he imagined the door swung half open and inside he could see neon, orange and green lights blinking, and bats blowing trumpets and alligators playing trombones, and where he could see snakes screaming. Weird masks and actors’ clothes hung on the wall, and if he stepped across the sill and reached for them, he knew that he was committing himself to his own destruction.”

It’s easy to imagine Ali’s psyche stepping dangerously close to the room — his hand shaking as it touched the door — while sharing the ring with Frazier and Foreman and Norton. The metaphor must have helped him visualize and define fear, and thus figure out a way to side-step it and stay focused while withstanding the onslaught of what may have been the strongest field of heavyweights ever. “Just don’t go into that room and you’ll be safe; do everything you can to stay out of there,” he must have told himself.

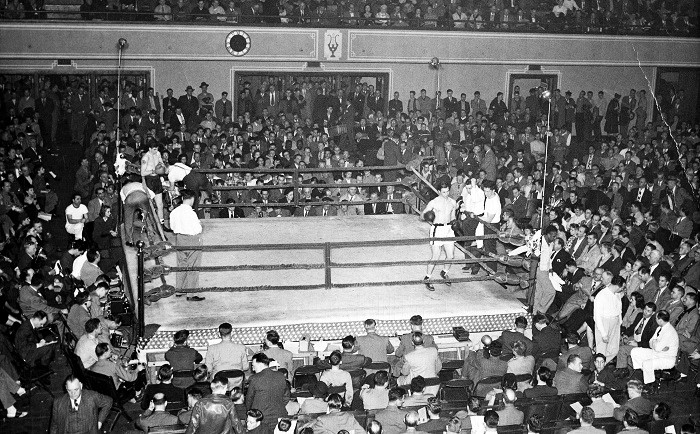

But Ali wasn’t the only one to profit from the “Near Room” construct, as Plimpton realized that the image accurately portrayed the apprehension, and even the occasional panic, he felt when Sports Illustrated asked him in 1959 to box three rounds with Archie Moore and then write a piece about it. A tall order indeed for someone of Plimpton’s constitution, his physical disposition being almost comically anti-athletic. As a youngster, in what should’ve been his physical prime, he got cut from every varsity team he tried out for. “Tall as a reed, fragile as a stick, I ended up in the band playing the bass drum.” That’s without mentioning his fragile nose or his “sympathetic response,” an involuntary reaction causing him to weep prominently whenever hit on the face.

So it goes without saying that Plimpton needed all the help he could get if he was going to survive three rounds with the light heavyweight champion of the world. Still, it comes off as charming that, in complete accordance with his patrician origins and Ivy League education, Plimpton began preparations for his mission at the library, reading every boxing manual he could find before taking the more useful step of enlisting a professional trainer.

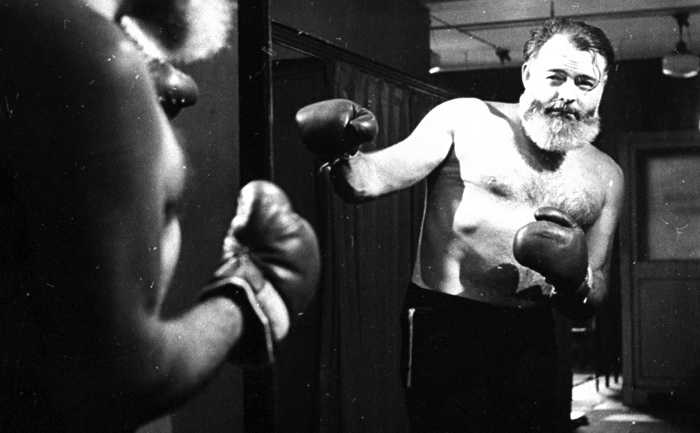

When he wasn’t training or studying at the library, Plimpton collected tales of other writers who boxed with professionals, and while recounting them he conveys the sentiment that many did so out of curiosity about what it’s like to share the ring with a specimen much more fearsome than themselves, and perhaps were even trying to make a point regarding their manhood in daring to engage an athlete who punches people for a living—famous names like Hemingway and Mailer immediately jump to mind here.

But Plimpton’s incursion into the world of prizefighting stands in defined contrast to those of his colleagues, as his self-deprecating tone and good-natured approach make it seem as if his interest in boxing in general, and his taking on the Moore assignment in particular, were the natural result of the same universal curiosity which compelled him to pitch in a major league game, play quarterback for the Detroit Lions, and play the piano in front of a live audience at the Apollo Theater. Plimpton’s was an all-engrossing, wide-eyed, child-like curiosity, one that moved him to experience—and record in writing—as much of life as was possible. Those are the two motivations on which Plimpton built his reputation and his entire career: diving into the extraordinary, and then writing about it through the eyes of a man whose intelligence and storytelling prowess more than matched his self-effacement.

After an arduous psychological and physical preparation, and after the Moore encounter that followed, George visited Ernest Hemingway in Cuba to tell him all about it. ‘Papa’ Hemingway, who makes a number of appearances in Plimpton’s book, was interested in a much more restricted set of human experiences than Plimpton, namely those that fed and reinforced the macho mystique with which his name is now synonymous. The difference in disposition between the two writers becomes obvious when Plimpton tells Hemingway how he got licked by Moore. Hemingway laments that Plimpton didn’t come to train with him, and urges the younger man to get back in the ring as soon as possible: “The elephant hunter can’t begin to call himself one until his fiftieth elephant,” Ernest tells George. Cue to a few moments later, and the reader finds Plimpton absorbing hard punches from Hemingway, the unfortunate sympathetic response instantly wetting his eyes. How could that meeting have ended any other way?

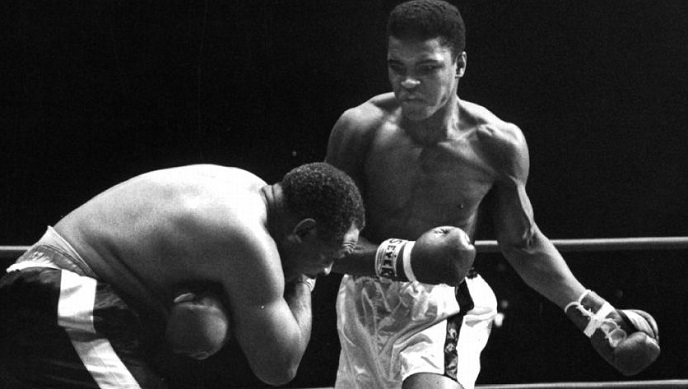

Despite Shadow Box being known as the boxing chapter of Plimpton’s efforts in participatory journalism, the Moore assignment serves mostly as an introduction to the book, and as a sort of farewell to the pre-Cassius Clay boxing world. The section that follows the Moore assignment deals with the Moore vs Clay fight in which a young, brash, widely-disliked Cassius Clay easily does away with “The Old Mongoose,” finishing the contest in round four, just as he had predicted, and thus becoming the “crown prince” of the heavyweight division. But Plimpton—who would come to admire Ali—was neither moved nor impressed on the occasion of that duel. “It was pretty awful. Clay did this miserable victory stomp—Archie on his knees trying to get up,” he tells to a random girl in a bar after the fight. If Plimpton’s “fight” with Moore was akin to a tourist taking a backstage tour of the Theater of the Unexpected, the future Muhammad Ali’s fight with Moore symbolized the raising of the curtain to one of the grandest shows in boxing history: The Ali Era.

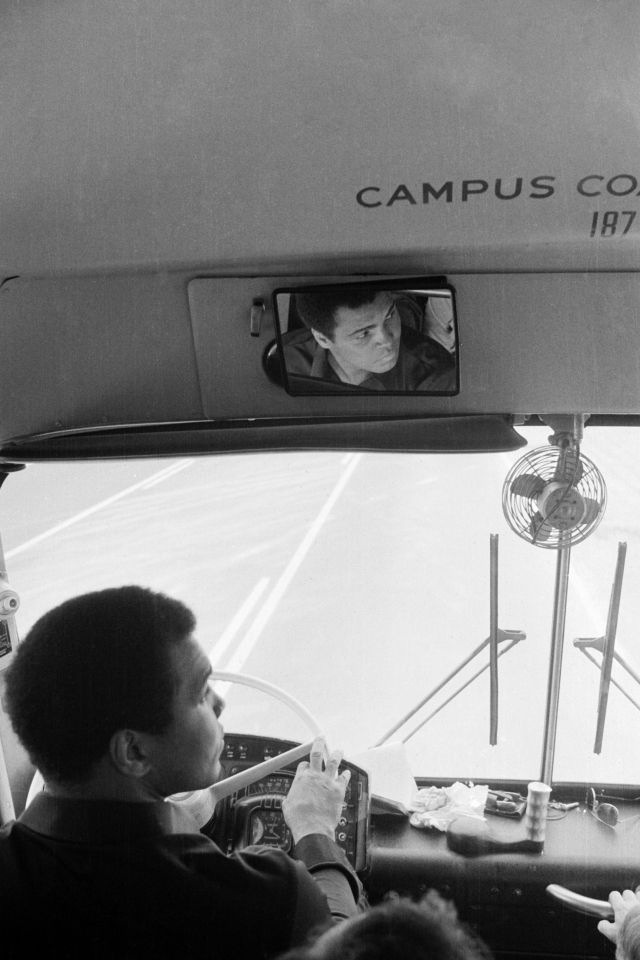

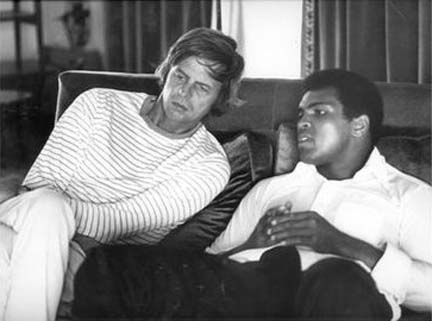

Plimpton played witness to many different facets of Muhammad Ali, and that may be the strongest aspect of Shadow Box. The champion’s playfulness, the self-confidence bordering on arrogance, and even the mean streak, all surface at different points. Particularly jarring is Plimpton’s recounting of the bus trip—with Ali at the wheel—in which the newly crowned champion’s entourage leaves Miami following the first Liston fight and heads north for the rematch. When the traveling circus comes to a screeching halt in a Georgia diner that won’t serve blacks, the scene is set for a confrontation between Ali and his colorful cornerman, Bundini Brown, who had requested to stop there. All the shared joy at Ali’s winning the championship of the world is rendered useless and artificial in a matter of seconds and once back on the road, a furious, humiliated Ali rages at Bundini, “What’s the matter with you—you damn fool! You got showed! You belong to your white master!”

A recurring idea keeps popping up in Plimpton’s tales of Ali, that being the author’s sense of guilt at having done nothing to keep Muhammad from losing his crown to the federal government for refusing the draft. But it eventually becomes clear to Plimpton that not only would any efforts to that effect have been useless, they would also have been unwelcome by Ali himself. For a champion of Ali’s stature—and for a champion as aware of said stature as Ali was—nothing less than complete self-reliance would do.

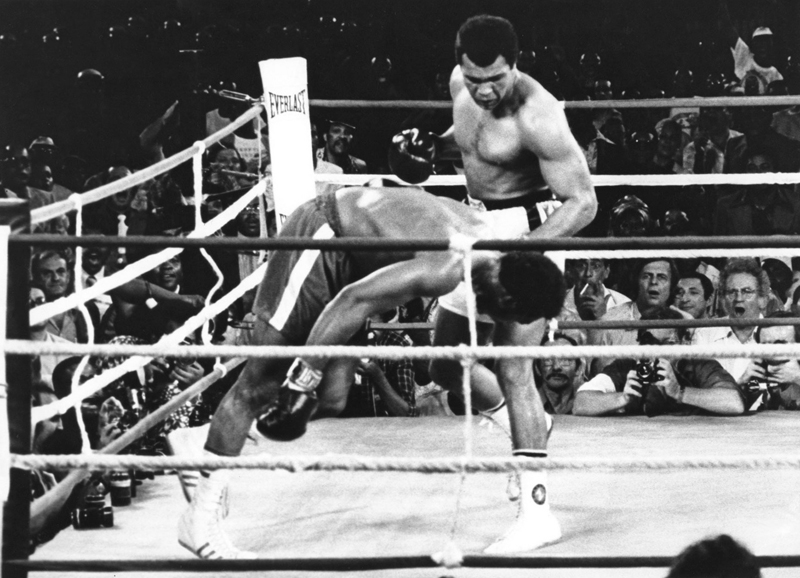

This is the narrative that drives the tale of Ali vs Foreman, fought in Zaire in a surreal atmosphere, financed by a military dictator and promoted by one of the most bizarre personalities in an industry plagued by them. As the world’s eyes turned to Africa for the monumental clash, with scores of writers descending upon Zaire for the boxing event of a lifetime, Plimpton recounts the painfully tedious way in which Ali’s and Foreman’s days passed by, the nervousness felt by everyone regarding Ali’s chances in the fight, and the paranoia-fueled feats of those condemned to do nothing but wait and report in a strange land far from home and all familiarity.

Plimpton does justice to the magnitude of the event, conveying the anxiety and confusion that reigned through the buildup and all the way to fight day. As if to properly reflect the quickly changing moods, his own writing alternates between chaotic and methodical: at one time the writer becomes obsessed at ‘collecting’ death stories and death fantasies told by his writing colleagues; at other times he frets in self-doubt over the backup writer that his employer dispatched to pick up the writing ball Plimpton may fumble; and yet other times he’s trying to keep up with a substance-fueled Hunter S. Thompson and his attempts to smuggle ivory out of Africa.

What may come across to some readers as unfocused writing, others will find delightful in its diversity and free-wheeling nature, though the lone fault of Shadow Box may be that some of the digressions go on too long, particularly if you think Plimpton should focus on boxing alone. However, even those who label Plimpton’s digressions a defect will agree they’re worth putting up with to get to the meat of Shadow Box; invariably, Plimpton’s writing is first-rate, his stories always full of vivid detail and delightful turns.

Moreover, Plimpton has a way of converting his access to the figures he writes about into rich, though never overbearing, portraits that present already well-known people and events in a novel angle. Angelo Dundee tells him behind which ear he keeps a vial of smelling salts (the right one), and in which shirt pocket he keeps his Q-tips (the left one). Bundini tells him the story of how he convinced Ali to bring him into his team, by haranguing Ali’s former handler, “The man best move to care for a fighter packing people into the Garden up to the rafters and the seats where before there was nothin’ there but pigeons!” A demoralized, beaten Ali, following his painful—in more ways than one—defeat at the hands of Joe Frazier, moans and complains in his dressing room, “Don’t hold me, Bundini. Damn! I’m sore. I’m sore in the neck. I’m sore in the ribs.” Of Foreman’s surprising defeat to Ali, the same Archie Moore who drew blood and tears from Plimpton tells him, “As they say in the idiom of Brooklyn, (Foreman) blew his cool.”

One gets the feeling Plimpton is able to do all this not only thanks to his writing talent, but also because of his being a fan of boxing first and foremost, a sense supported by the memory Plimpton chooses to represent his journey to Africa. After the fight was over and Plimpton had left Ali’s dressing room, he stared out at the emptying stands of the stadium in Kinshasa, his eyes eventually settling on the ring, now crowded with boys feinting at each other and punching the air, re-enacting over and over the final sequence in which Ali sent Foreman to the canvas, and granting Plimpton the chance to relive the moment a few more times, before the joy and “contentment” of having witnessed it faded away. “It was getting difficult to remember the exhilarations,” writes Plimpton. “So often, the joy of having been a witness seems to slip away with infuriating ease, however one tried to hang on to it.” The words echo a feeling universal to sports fans of all stripes, and which could have only been penned by a fight fan himself. –Rafael Garcia

I enjoyed “Shadow Box” very much. George Plimpton, together with AJ Liebling and Norman Mailer, represent the very best of boxing writing.

Liebling is unmatched.