Fight City Legends: The Barbados Demon

Boxers failing to make weight before a fight is an ever-present concern, one that angers many fans and rightfully so. It’s a fundamental requirement and a true professional ensures he fulfills his contractual obligation. But whether it’s Floyd Mayweather intentionally coming in overweight against Juan Manuel Marquez back in 2009, or Canelo Alvarez insisting on catch-weights for different bouts, or Adrien Broner and Julio Cesear Chavez Jr. showing complete disregard for weight limits, all demonstrate that boxers do often seek to gain an edge either by forcing an opponent to dry out, or by bringing some extra poundage into the ring.

Obviously a potentially unfair advantage exists if one pugilist has made the necessary sacrifices to reach the required weight and the other has not, or if one fighter is significantly heavier than the other. But that said, some fans may be surprised to learn that many greats of the past regarded weigh-ins and weight advantages as things with about as much bearing on their dangerous trade as the relative humidity or an opponent’s shoe size. Fearless gladiators like Sam Langford, Mickey Walker and Jimmy Wilde never turned away a challenge for this reason, especially as they knew how to turn an adversary’s greater weight into a disadvantage.

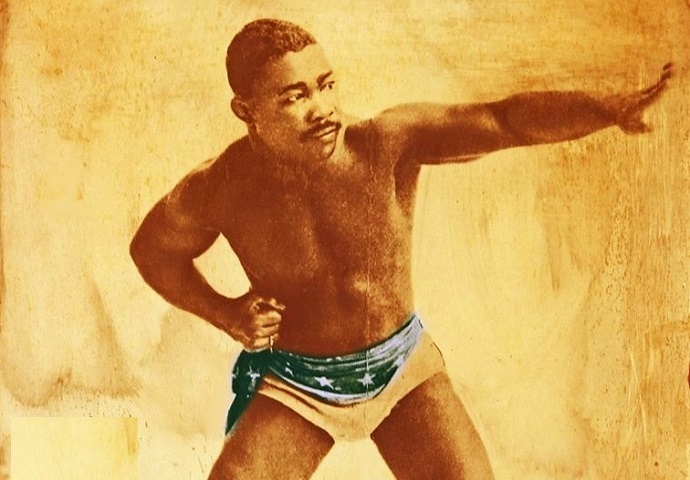

And so it was for the original Joe Walcott, not to be confused with world heavyweight champion Arnold Cream who named himself Jersey Joe Walcott, in tribute to the legendary warrior who he regarded as the greatest fighter who ever lived. The original Walcott was born in British Guiana, but spent most of his childhood in the Barbados before moving with his family to Massachusetts, where as a youth he worked at various jobs including helping to sweep up in one of Boston’s many fight clubs. It wasn’t long before Walcott began training and sparring and learning the craft and his natural abilities soon came to the fore. He turned pro in 1890 at the age of just seventeen, and within five years he had established himself as one of the most fearsome and powerful battlers in America. Fight fans and pundits of the day regarded him as nothing less than the hardest-hitting welterweight they had ever seen.

And so it was for the original Joe Walcott, not to be confused with world heavyweight champion Arnold Cream who named himself Jersey Joe Walcott, in tribute to the legendary warrior who he regarded as the greatest fighter who ever lived. The original Walcott was born in British Guiana, but spent most of his childhood in the Barbados before moving with his family to Massachusetts, where as a youth he worked at various jobs including helping to sweep up in one of Boston’s many fight clubs. It wasn’t long before Walcott began training and sparring and learning the craft and his natural abilities soon came to the fore. He turned pro in 1890 at the age of just seventeen, and within five years he had established himself as one of the most fearsome and powerful battlers in America. Fight fans and pundits of the day regarded him as nothing less than the hardest-hitting welterweight they had ever seen.

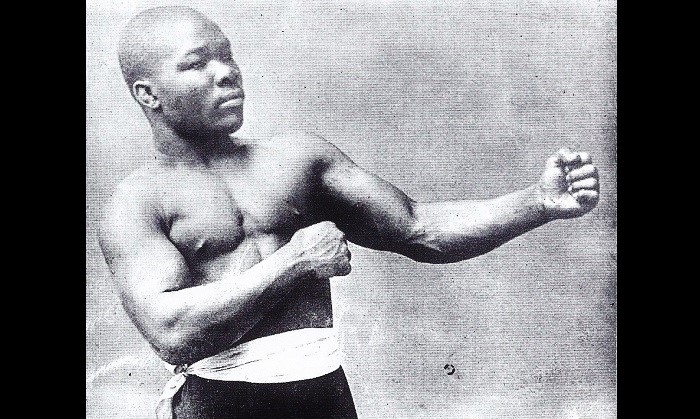

Walcott’s abilities stemmed in large part from his physical gifts which had nothing to do with size and weight and everything to do with natural strength, power, stamina and durability. Standing under 5’2″, Walcott sported a massive upper body for his stature with an 18 inch neck, a 41 inch chest, and long, powerful arms. Nat Fleischer described him as a “sawed-off Hercules” and “an abnormally powerful puncher.” The National Police Gazette marveled at Walcott’s power, stating that one clean strike from Joe was equal to five from his opponent.

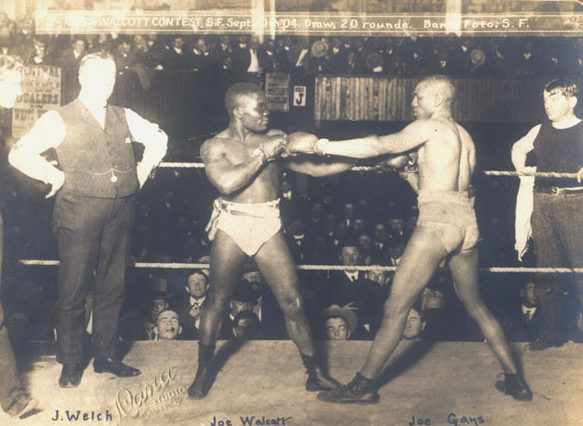

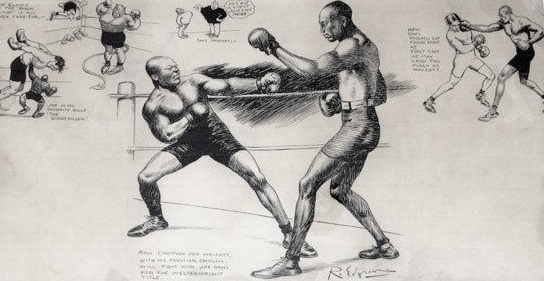

Similar to other black fighters of the time such as George Dixon, Joe Gans or Sam Langford, it was difficult for Walcott to secure a shot at a world title, or to get a fair shake. Having established himself as one of the best welterweights in the world, the current champion, Tommy Ryan, avoided him, forcing Walcott to try for Kid Lavigne’s lightweight title in 1897. Drained by the effort to make weight, Walcott dropped a close decision. The following year he lost another close decision in an attempt to win the welterweight title from fellow great “Mysterious” Billy Smith. Walcott eventually got another chance at the welterweight championship when he faced Jim (“Rube”) Ferns in 1901 and this time Walcott won by a knockout in five. He would keep the title until 1904, when he lost to the legendary Dixie Kid by controversial disqualification (it was later established the referee had bet on Dixie) in the first world title match between two black boxers.

But as any boxing historian knows, championship belts really had very little to do with true boxing greatness during Walcott’s era. For example, Langford received only a single chance to win a world title in his incredibly long career, that being a fifteen round war with Walcott which ended in a draw, but Sam is rightfully regarded as one of the greatest fighters of all time. Instead, it is Walcott’s many fights against much larger opponents that sets “The Barbados Demon” apart as a genuine ring immortal. Frustrated by the difficulties in securing matches against the best welterweights of the day, Walcott issued public demands to take on the better big men instead, and when given the chance, amazingly, he usually bested his much taller and heavier opponents. Fittingly, it is Walcott who is credited with the timeless maxim, “The bigger they are, the harder they fall.”

To illustrate, Walcott’s manager, Tom O’Rourke, also handled Sailor Tom Sharkey, a top heavyweight contender of the time who twice went the distance with heavyweight champion James J. Jeffries. O’Rourke stated that he had to stop Walcott from sparring with Sharkey because Joe kept knocking Sailor Tom down. Another example: the August 28, 1895 Boston Herald reported that Walcott weighed just 138 pounds against Dick O’Brien’s 155, but O’Rourke was so confident in his fighter that he waived the weight. Walcott knocked out O’Brien in the first round. Walcott also beat a number of top middleweights including Jack Bonner, Tommy West, Kid Carter, George Cole, and Joe Grim. He fought light heavyweight champ George Gardner twice in non-title tilts, winning once by twenty round decision.

But perhaps the best example of Walcott’s amazing ability to defeat much larger men is his win over Joe Choynski, a formidable and powerful heavyweight who had competed with the likes of Sharkey and Jeffries, as well as against James J. Corbett, Bob Fitzsimmons and Jack Johnson. Choynski outweighed Walcott by some thirty pounds and was a five-to-one favorite, but Walcott demonstrated his astonishing skill and power when he floored Choynski multiple times en route to winning by a seventh round stoppage. The contemporary equivalent of this would be Shawn Porter taking on say Joe Smith Jr. and winning by knockout.

Walcott’s ring immortality is based on such amazing feats, as well as the esteem he was held in by his contemporaries. Heavyweight champion Jack Johnson rated Walcott as one of the most powerful hitters of all-time. Langford himself paid Walcott the great tribute of ranking him at the very top when it came to the most dangerous puncher he had encountered in his incredibly long career. “He was the hardest hitter I ever met,” stated Langford, recalling their 1904 match which, according to reports, was a furious and action-packed fifteen round war. “Never before or since have I been hit as hard and as often … and I never landed more blows than I hurled into Joe Walcott that night.”

In 1904, Walcott accidentally shot himself, injuring his right hand, and he did not compete for two years. He returned to the ring greatly diminished before finally retiring in 1911. Unfortunately, Walcott had lived fast, squandering his ring earnings on the usual vices, and in his later years he struggled to get by before being hired as a custodian for Madison Square Garden. He died in 1935 after being struck by a car.

Both Nat Fleischer and Charley Rose rated Walcott as the best welterweight of all time and historian Monte Cox states that his “success against men of much higher weights leads one to believe that no modern welterweight could have gone the distance with him.” Doubtless, “The Barbados Demon” forever stands as a true, pound-for-pound ring great and perhaps the best “giant killer” the sport has ever known. — Neil Crane

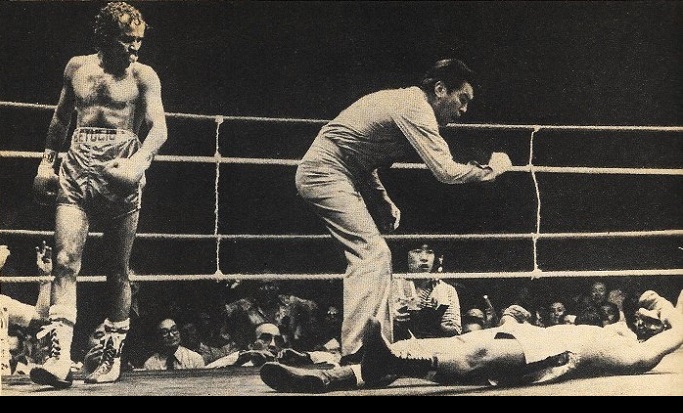

Sometimes I see these images and think, if I was born at that time… I wish I could see them in front of me.

If they ever discover time travel..

“Barbados Demon”- Perfect title for a perfect boxer.