April 18, 1998: Eubank vs Thompson

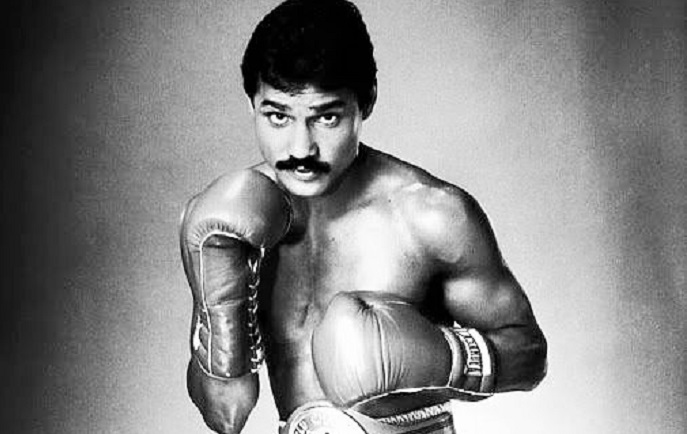

Chris Eubank was always a mighty specimen. Sleekly muscled during his reigns as middle and super-middleweight champion, it should have come as no surprise when he gatecrashed the cruiserweight division in scarily sinewy physical form. Walking to the ring to face WBO champion Carl ‘The Cat’ Thompson, Eubank adopted a familiar strut, seemingly unperturbed by the prospect of facing a naturally bigger man. The locus of his self-assurance was obvious. Not having bothered with a robe, warm-up sweat glistened on his brawny torso as “Simply The Best” boomed out of the PA. Eubank took his time on the gangway, striking poses and flaring his nostrils at the crowd.

The Brighton boxer hadn’t piled on the additional 19 pounds by scarfing Big Macs and skipping roadwork. He’d trained with a demonic intensity and looked very much like the Chris Eubank we all knew, only bigger. Broader across the chest and back, and with a stronger base, there wasn’t an ounce of fat on him. He seemed custom-built for a Homeric battle. It was just as well.

Only two Brits had succeeded in claiming world titles in three weight classes. Bob Fitzsimmons had been the first, completing his treble by claiming the light heavyweight title in 1903. Nine decades passed before the feat was repeated, Duke McKenzie adding the WBO super-bantamweight strap to his flyweight and bantamweight honours. Now Eubank, always a polarising figure among the UK fight fraternity, was attempting to inscribe his name in the history books.

Rather than challenge the eminently beatable WBA light-heavyweight champion Lou Del Valle, or IBF holder Reggie Johnson, Eubank had elected to bypass the division altogether, announcing his intention to fight Carl Thompson. Eubank’s reasoning was simple. “The only way you get into the legendary ranks,” he averred in his typically dramaturgical diction, “is when you do what the critics say you can’t.”

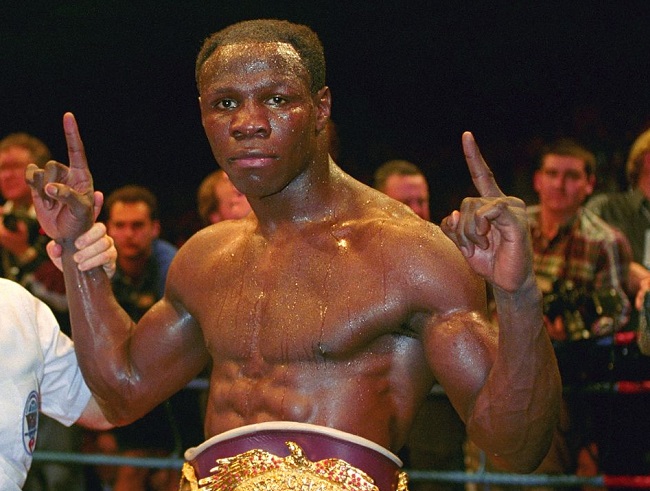

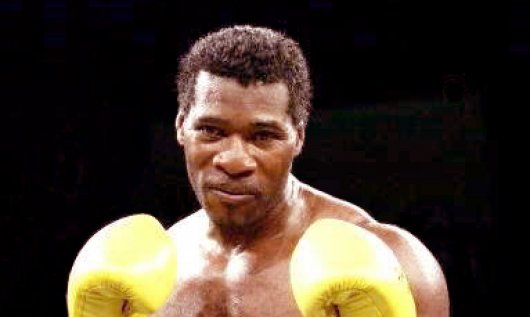

A chunkily-built road warrior with a formidable punch, Thompson had recently ventured to Hannover, Germany for a rematch with Ralf Rocchigiani, dethroning the German and securing both the world title and the respect that had eluded him during his nine-year career. His first title defence would take place on home soil, at Manchester’s Nynex Arena, on the undercard of Naseem Hamed vs Wilfredo Vasquez. The opponent would be Chris Eubank, a veteran of fifty fights with a point to prove. But if Eubank was a showman, prone to pontification, a boxer who wished he was an aristocrat, his attitude was antithetical to Thompson’s. “The Cat” was a blue-collar type, a quiet but headstrong work horse with no pretensions to a higher calling.

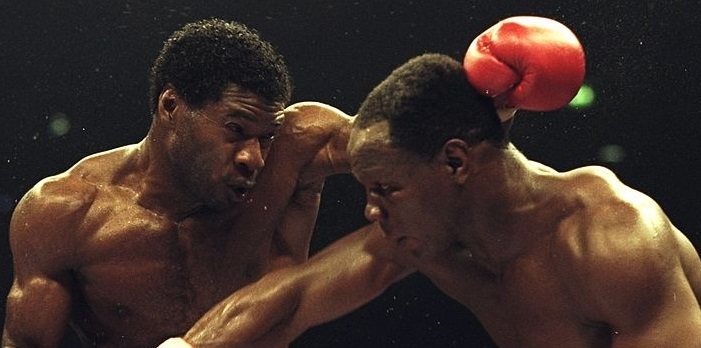

Eubank vs Thompson was a thrilling war from start to finish. The challenger started explosively, as if to make clear to all why he, and not Thompson, had been British boxing’s torchbearer through the past decade. He out-sped the champion, landing bold punches to body and head and tying the heavier man up when he got too close. At the conclusion of the first stanza, Eubank back-pedalled towards his corner before changing his mind and swaggering across the ring, smirking at the howling crowd.

Keen to impress his greater size on Eubank, Thompson threw every punch with bad intentions, catching his man with a forceful right at the start of the second, whereupon Eubank spent the rest of the round on the move, ramming his jab at the advancing champion and jerking his head away when Thompson launched bombs. With thirty seconds left, Eubank put together a rapid four-punch combination: right uppercut, straight right, left hook, right hand, the final blow punctuating the salvo by booming off Thompson’s jaw. The champion lost his footing slightly and dropped his hands, time enough for Eubank to pitch a powerful right hook and continue the onslaught. Only a few clean blows landed but Thompson ceded ground, stumbling confusedly towards the corner as Eubank sought to administer the coup de grâce.

Fighting desperately to defend his newly-won title, and with his back to the ring-post, Thompson slung an agricultural right hand that was so wild and off-target that it almost sent him sprawling headfirst through the middle rope. For some reason, almost as though he’d lost his train of thought, Eubank called off the assault, commencing to peer inscrutably at Thompson with both gloves held in front of his stomach. “Now he’s indulging in psychological warfare,” surmised Ian Darke, commentating for Sky Sports. Afterwards, many voiced their belief that Eubank had simply lost his killer instinct, an accusation that had plagued the fighter since the tragic rematch with Michael Watson. When the bell rang Thompson sportingly tried to touch gloves with Eubank, but the challenger ignored him and struck a defiant pose, muscles bristling.

Having recuperated between rounds, Thompson meted out some punishment of his own in the third. To the surprise of many, Eubank held firm, withstanding a heavy uppercut and full-bloodied right before walking calmly away and finding openings to shoot combinations. There were some good exchanges during the fourth with Thompson landing two uppercuts early in the round and Eubank responding with a vigorous right that appeared, for a moment, to have folded Thompson like a deckchair. The big man’s torso buckled and he appeared to stare at the canvas, as though searching for dropped change. As soon as Eubank rushed towards him though, Thompson planted his feet and swung for the fences as Eubank held his ground and loaded up himself. An underrated combination puncher, he landed a crisp one-two followed by a swift right uppercut that connected with Thompson’s chin and sent him toppling sideways to the floor.

After receiving the mandatory eight count, Thompson waited for Eubank to advance, which he did, though not without caution and forethought. Once more, Eubank spent more time savouring the fact that he had hurt Thompson than actually pressing home the advantage. He owned the centre of the ring for the remainder of the round, but he failed to bait the hook. Before the bell, it was Thompson landing a mean right hand, ably demonstrating that he’d shook off the cobwebs.

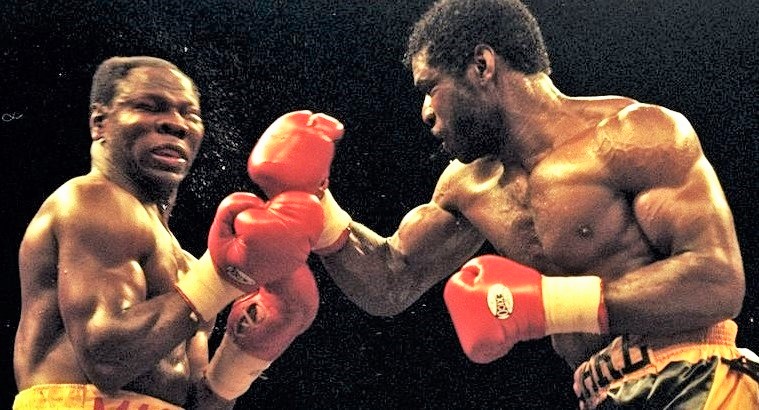

Eubank may have made the early running, but he’d been marked up by Thompson’s powerful punches. His left eye began to close in the fifth, and his right didn’t look much better. He moved sluggishly during this round, his shots lacking their previous snap, and Thompson took advantage to administer several bludgeoning rights. Despite this, Eubank remained the puncher. Thompson clumsily walked on to a backhand with thirty seconds remaining and was forced to beat a hasty retreat. This time Eubank went for the kill, launching right-hand howitzers, most of which missed their target. In the ensuing tangle, both men almost tumbled over the top rope. At the bell Eubank held his right glove aloft, as though hailing its awesome power. Statistically, he was in complete control: he’d outscored the champion 155-112 in landed punches, connecting with 47 body shots to Thompson’s eight.

Thompson produced good work in the seventh, relentlessly pursuing the challenger across the ring and out-hustling him at close quarters. Not for the first time Eubank doubled down on his power, landing a right hand and a left hook, the latter connecting as Thompson threw his own haymaker. Knocked off-balance – by Eubank’s punch? by his own mis-timed bazooka of a right? – Thompson then did a little dance and fell against the ropes. “He’s all over the place!” cried Darke. “And Eubank stands off! Why did he stand off?!” Why, indeed.

“He thought he could hurt me but I played possum all the way through,” said Thompson years later, somewhat disingenuously, to this writer’s mind. Eubank certainly buzzed him, but the Mancunian’s doughty style and tremendous stamina kept him in the fight. But whatever he says now, no doubt Thompson was glad of his opponent’s reticence in a few of the rounds.

Though Eubank looked as though he were carved out of stone, the burden of facing down a naturally bigger man began to take its toll as the contest wore on. The exchanges became more gruelling with every passing round. Eubank spent most of the ninth on the ropes, Thompson raining down blows on his guard, and he was on the receiving end again in a torrid tenth. In the final two rounds, Eubank was forced to reach deep into his soul for the reserves of spirit that had seen him through such internecine battles as those shared with Collins, Benn and Watson.

In the heat of combat, with a redoubtable Thompson landing clean, punishing blows on his pumped-up frame, Eubank did not founder or wilt but he did suffer greatly for his art, surrendering a razor-thin but unanimous decision after twelve gladiatorial rounds. Beaten, bruised but never cowed, he had shown evidence of both his iron chin and indomitable will. Perhaps his courage offered him some consolation during a two-day stint in the Manchester Royal Infirmary.

For Eubank, who had gone 47 fights unbeaten between 1985 and 1995, it was a second successive defeat, the other having come at the hands of a young Joe Calzaghe the previous October. He would fight once more, losing on a cut eye in a hastily-organised return with Thompson just three months later. At 31, his fighting days were over, but his place in boxing history was secure. In my eyes, he definitely merits a Canastota induction.

Thompson, for his part, lost the WBO title to Sheffield stylist Johnny Nelson a year later, the victim of a horrendously premature stoppage. Thereafter, he enjoyed a second spell as British champion, a second reign as European champion, and then two stints as IBO champion. In 2004, aged forty, Thompson had six losses on his ledger, five of them inside the distance. He was brought to Wembley Arena to provide fodder for a young David Haye, who had recorded ten knockouts in ten wins. Instead of giving the 23-year-old a few rounds, the long-in-the-tooth Thompson absorbed the early fire and pummelled the future heavyweight title holder to a fifth round stoppage. He would have one more fight, a year later, before retiring. — Ronnie McCluskey