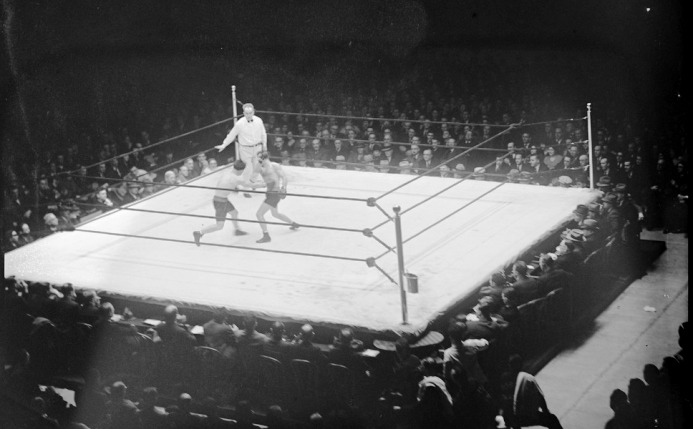

Aug. 19, 1995: Tyson vs McNeeley

A year ago, the boxing world was facing the possibility of a most unexpected event: an actual prizefight between Mike Tyson and Roy Jones Jr., the former “Kid Dynamite” vs the former “Captain Hook.” This most unlikely of duels between two former greats, who were both well into their sixth decade, did eventually take place, albeit as an exhibition match, the end result being a split draw after eight rounds of action. But at least as fascinating as the contest itself was the reaction of fight fans to the prospect of Jones and Tyson returning to the ring.

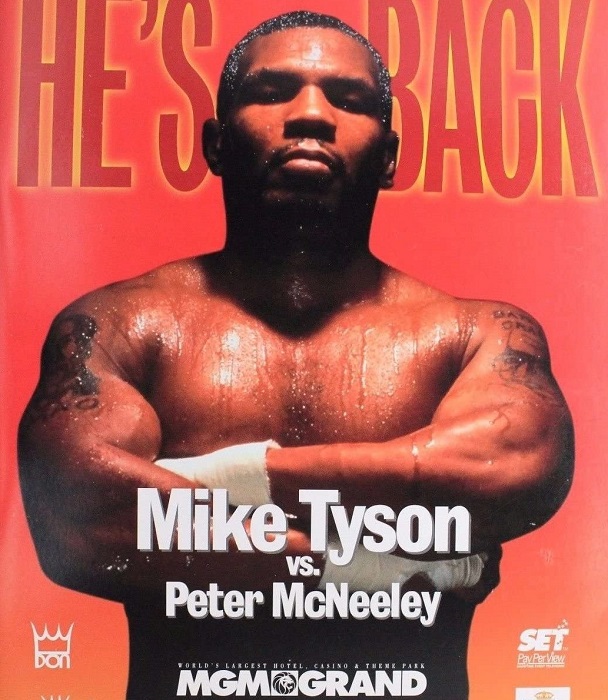

No one could deny that the official announcement of Tyson vs Jones Jr., complete with videos of the two Hall of Famers signing their contracts, generated some serious buzz, with the hype embracing the spectacle of a legit heavyweight “comeback” fight for Tyson, as if a 54-year-old “Iron Mike” was on his way to reclaim the undisputed heavyweight title. Admittedly, Mike did look sharp in the short training videos that were released, but only the most deluded of fight fans would mistake that fitness for the ability, or desire, to compete professionally again. In any case, Tyson is no stranger to the hype of the big comeback fight, as he had several during his pro career. And undoubtedly the biggest one took place on this date twenty-six years ago.

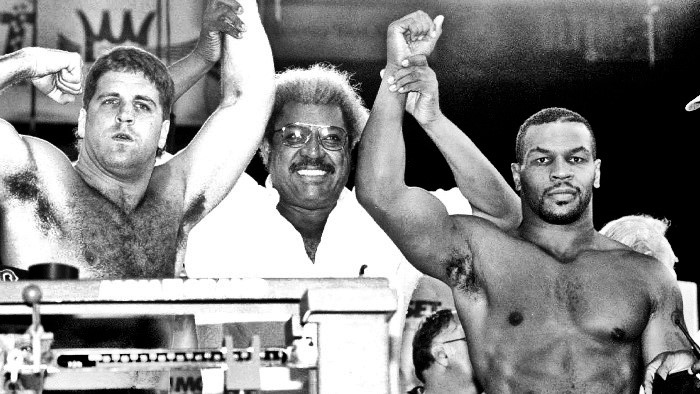

Having been convicted of rape in 1992, Mike Tyson emerged from prison in March of 1995, and to say that the boxing world was eager for his return would be a gross understatement. “Watching the heavyweight division the last three years,” quipped Bert Sugar at the time, “has been like watching people getting haircuts.” Emerging from prison, anything was possible for Mike Tyson. It could have been the opportunity for a fresh start, his return a story of redemption, of second chances. Great comebacks are what religions are built on after all. But promoter Don King was waiting in the wings, hustling his own shallow gospel, and Tyson’s return would be sold like a summer blockbuster, a vulgar exercise in gimmick and bad faith.

In retrospect, the die had already been cast for the former champion during his trial. In a surprising turn, the strategy of his legal defense was to paint a portrait of Mike Tyson as an absolute brute, a villain, a man who everyone knew could not be trusted. Testimony after testimony depicted Mike as a crude beast and anyone who went near him, the defense argued, had to know what they were in for. Innocent, in other words, by reason of savagery. This was the branding, orchestrated by King, that took root in the public mind. This was the background against which Tyson, less than a week after his prison release, announced his intention to fight again.

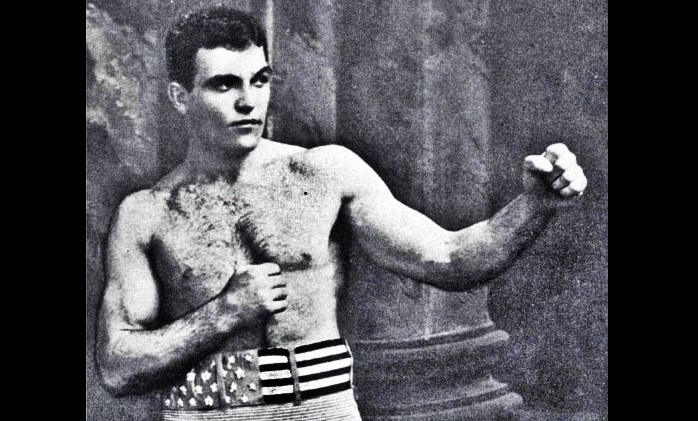

Details for the big comeback bout emerged slowly, perhaps none more surprising than the name of his opponent: “Hurricane” Peter McNeeley. Virtually unknown, McNeeley did sound good on paper, or at least interesting. He was a third generation club fighter from Medfield, Massachusetts. His grandfather nearly made it to the Olympics; his father had challenged Floyd Patterson for the title back in 1961, and McNeeley himself boasted a record of 36-1-0. But numbers can be deceiving. In fact, like a display in a grocery store window, McNeeley was a tomato can stacked upon other tomato cans, his thirty-seven opponents holding a combined record of 213-455-22. By comparison, Tyson entered the fight 41-1-0; his opponents’ combined record was 738-163-13.

McNeeley immediately became a locus for puns, zingers, and derogatory one-liners. Destined, it seemed, to be a target. On the promotional blitz, he appeared on David Letterman, the host dubbing him “the Rodney Dangerfield of boxing.” Boston Magazine, practically a hometown journal for McNeeley, dubbed him “The Great White Hopeless.” McNeeley was the sort of character only the boxing world seems capable of producing, pure “palooka,” straight from central casting. Yet for all his rough edges and questionable pedigree, McNeeley came across as a likable enough pug, offering a kind of tempered self-confidence that said “don’t count me out.”

On the night of the fight, McNeeley walked out to a track titled “The Angry Song,” by a band from his hometown, Whirling Vertigo. The music was far less intimidating than its title, and when McNeeley went to remove his robe with a dramatic tug, he forgot to first untie the belt and the robe stayed on. Defeated already by his wardrobe, his chances against Mike Tyson did not look good.

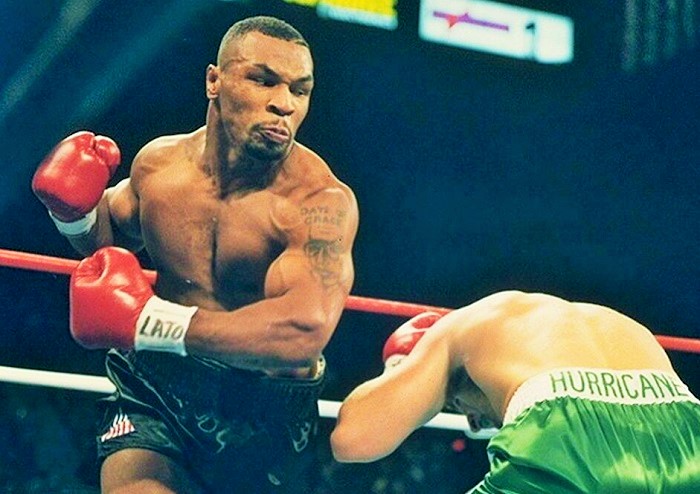

The former champ, conqueror of Larry Holmes, Michael Spinks and “Razor” Ruddock, made his entrance wearing his signature cut-up towel, black trunks and boots with no socks. Hype-man “Crocodile” shouted alongside him. Tyson had converted to Islam while in prison, and the tattoos he had acquired while inside, including the faces of Che Guevara and Mao Tse-Tung, were visible to all. With Redman’s “Time 4 Sum Aksion” playing over the loudspeakers, Tyson’s ring walk brought to life the boogey-man envisioned by the white panic over gangsta rap, and his fans in the MGM Grand ate it up.

From inside the ring, Tyson paused to survey the sell-out crowd and “Iron Mike” almost smiled. But he restrained that nostalgic impulse and, like an actor who has momentarily broken character, quickly regained his stoic composure, as if to remind everyone of the part he was playing, that “the baddest man on the planet” was back.

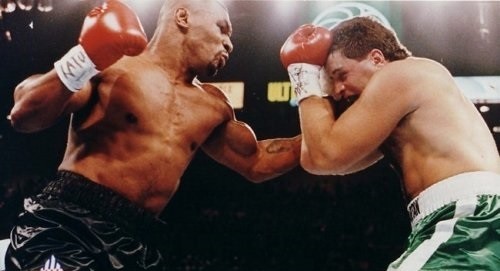

At the bell, an adrenaline-charged McNeeley literally ran across the ring to do battle, colliding with the former champ like an offensive lineman. Ducking a left hand, Tyson responded with two right hooks, dropping a surprised McNeeley, who rebounded from the canvas like a shot bullet and then ran nearly two laps around the ring before referee Mills Lane could stop him to administer the standing eight. The audience roared their approval and McNeeley again bull-rushed Tyson. Toe-to-toe, the heavyweights traded blows and, for a brief moment, McNeeley actually gave better than he got. Mike’s famed uppercuts couldn’t find their target, and a shove from McNeeley kept the shorter Tyson on the ropes.

The fighters were separated by Lane and Tyson quickly rallied, launching a left hook that wobbled McNeeley. Then a stiff right uppercut found its target, dropping “Hurricane” for the second time, who went down face first, but again beat the count. But if his eyes followed Tyson, his body was swaying precariously and it was then that McNeeley’s trainer took matters into his own hands. He didn’t merely throw in the towel, he jumped through the ropes to end the fight. As a result, the outcome was ruled a disqualification rather than a TKO, but it’s worth noting that McNeeley himself never quit. Cliché as it sounds, the unheralded “tomato can” would have happily gone down swinging, though he would acknowledge later that he was overwhelmed and already out on his feet just ninety seconds into the scheduled ten rounder.

Tyson betrayed little emotion over his victory, as expected. Eager to exit the glare of the spotlight, he left the ring first while McNeeley stayed behind, stretching his fleeting moments of stardom. The crowd, which had come for the spectacle of blood, seemed puzzled by the outcome, unsure how to react. They cheered but their cheers lacked the zealotry that follows a definitive knockout. Tyson had won, yes, but were they satisfied? Did they feel robbed?

There was perhaps a realization growing in the crowd that many had come to see Tyson’s spectacular return, rather than his boxing. They had paid for the pageantry, not the pugilism, and they got what they paid for. They could now say they had been there, live and in person, to witness a legendary champion’s return, if not to glory, then at least to celebrity.

After McNeeley, Tyson would take a short-lived but earnest string of serious bouts that briefly positioned him as the once-and-future champ. He faced an undefeated Buster Mathis Jr, and in 1996 he won two titles fights, against Frank Bruno for the WBC title and then Bruce Seldon for the WBA belt, before a pair of losses to Evander Holyfield. But it was the McNeeley fight which proved to be the model for his later career, his bouts sold more on spectacle than skill. As Gerry Callahan put it in Sports Illustrated, Tyson vs McNeeley was “as close to a fix as Don King could get without prompting a congressional hearing.”

McNeeley would continue to fight for the next few years, though he never threatened to compete at the elite level. His most notable post-Tyson fight was against Eric “Butterbean” Esch in 1999; he lost by TKO in round one.

Tyson vs McNeeley was soon parodied by The Simpsons and McNeeley would also go on to parody himself, capitalizing on his fifteen minutes of fame in various advertisements. For America Online, he was shown using a computer before his trainer bursts in shouting “The kid’s had enough!” and waving the commercial off. For Pizza Hut, McNeeley was knocked out by a slice of stuffed crust pizza. This was all to be expected. The fight was ripe for parody because it already was, in its own crude way, a parody of the sport.

Twenty-five years later, Mike Tyson once again stepped into the ring, in a match which could also be termed a parody, though not a comeback. In a bid for some pre-fight publicity for “The Lockdown Knockdown,” Mike made an appearance on Discovery Channel’s “Shark Week,” the program billed as, believe it or not, “Tyson vs Jaws: Rumble on the Reef.” All the hype for the Tyson vs Roy exhibition match just proved once again that the Mike Tyson spectacle has never really ended. And it remains highly profitable. Make of it what you will, but Mike Tyson vs Roy Jones Jr. was the biggest boxing pay-per-view event of 2020, grossing over eighty million dollars in revenue. — Andrew Rihn