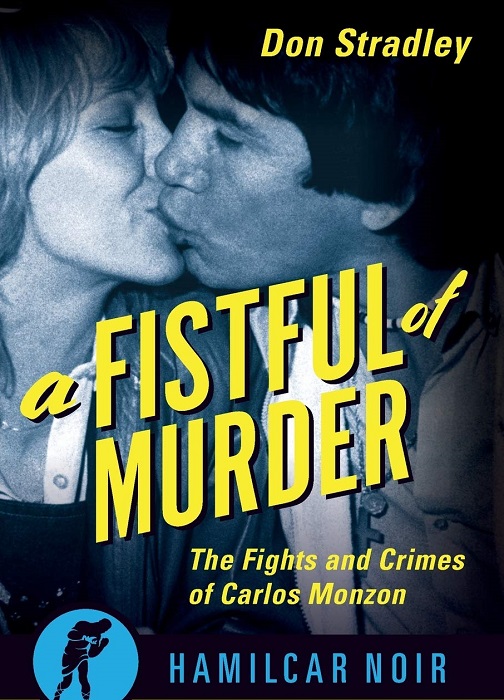

A Fistful Of Murder

Having already written a book about maniacal South American fighter Edwin Valero, Don Stradley doubtless experienced déjà vu when poring over the troubled tale of Argentine middleweight Carlos Monzon.

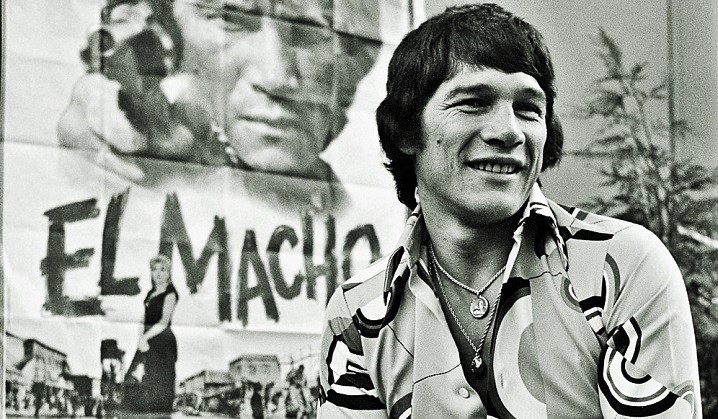

Like the hot-headed Venezuelan, the fighter they called “Escopeta” carried horseshoes in his gloves and lived a reckless life beyond the ropes, where he often fell foul of the law. In A Fistful of Murder: The Fights and Crimes of Carlos Monzon, Stradley rattles through the boxing legend’s soaring highs and crippling lows, sketching a compelling portrait of a gifted but self-destructive soul who transformed from a feral Santa Fe street kid into a renowned world champion.

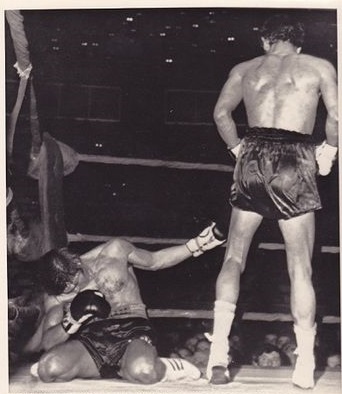

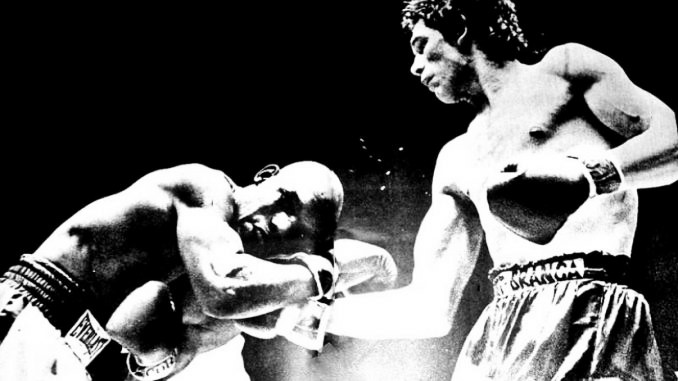

Sports fans will be drawn to the work thanks to Stradley’s considerable powers of description: he is probably one of the best fight writers operating today. And there are few better subjects than Monzon, a dark artist who pulverized a slew of rivals during a thirteen-year unbeaten streak that stretched from 1964 to the end of his career in 1977. Along the way he made fourteen successful title defenses and established himself as an all-time great in the middleweight division.

“It was probably in Santa Fe that his cold glare was developed,” writes Stradley in an early chapter. “In the decades to come, Monzon’s wicked stare would become chillier and scarier. It would take time, though, until his physical power was enough to back up his intense expression, but the end result was a glare that would become his trademark: a cold, mean look that said FUCK OFF.”

Unlike the authors of many boxing biographies, Stradley is not entirely in thrall to his subject. Although the awesome victories over Napoles, Valdes, Benvenuti, et al are eloquently chronicled, he observes that Carlos did not always win rave reviews: “When he’d first won the title, there was praise for his unusual style, the way he waited to strike, as one writer put it, with the patience of a sniper. As time passed, however, there was a tendency to point out his advantages in size, and little else. Remarks trickled in from English-speaking commentators during Monzon’s bouts that he was ‘crude but effective’ and ‘awkward but gets the job done.'”

One can sense Stradley’s sneer later in the book when he notes that “Monzon became a better fighter in retirement … The boxer who had often been dismissed as a classless thug was now revered as an all-time great.”

Of course, Monzon was an all-time great, of that there can be no doubt. Stradley ultimately agrees, marvelling at the 87-3-9 ledger “Escopeta” compiled despite battling “arthritis, a growing reliance on alcohol, and enough personal problems to give most men an ulcer.”

Despite its comparative brevity at 128 pages, A Fistful Of Murder manages to be several things at once: a character study of a brooding, malevolent archetype; a simple but absorbing boxing biography; and a pulpy story of a hideous crime barnacled with conflicting testimonies. To Stradley’s credit, he pulls the diffuse source material into a coherent whole and, like Berserk, his biography of Valero, the book can be consumed over the course of a few hours.

Throughout, the reader gains insight into what made Monzon such an omnipotent presence in the squared circle, and also what a piece of shit he was outside of it: abusive, arrogant, antisocial. He was a product of brutal poverty who “created a mask for himself, a kind of grandiose, all-powerful bully who was always in control… like all narcissists, his image was fragile; he was never far from becoming completely unhinged.”

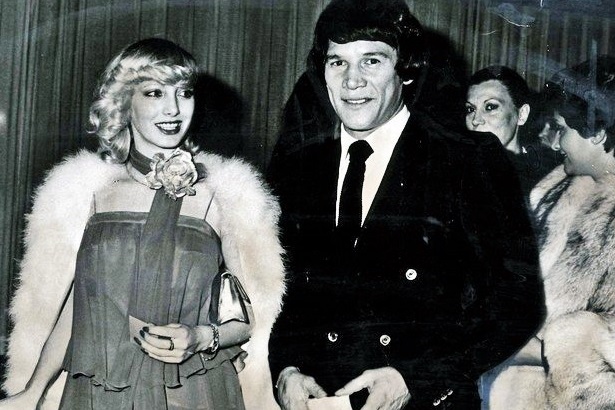

Those familiar with the Monzon story know how it all turned out: a dozen years after his retirement, the burned-out, coked-up ex-champ was convicted of strangling his ex-girlfriend, model Alicia Muñiz, before tossing her off the balcony of an apartment in the resort city of Mar del Plata. Six years later he died in a car crash while on furlough from prison, bringing the curtain down on a wild cautionary tale.

Of the aftermath of the murder, Stradley generously quotes from Argentine columnists and primary sources like Monzon’s son Abel, while also bemoaning the tawdriness of the whole tableaux: “Ultimately, the Monzon story became less an opportunity for sociological debate than a morbid peep show, a chance to show lurid photos of Alicia smashed on the bricks, her bare legs still beautiful even as the life flooded out of her. It was a big nasty dollop of Mar del Plata decadence, overflowing with surface glitter and cheap celebrity.”

Although the only people who definitively know what happened between Carlos Monzon and Alicia Muñiz are no longer with us, Stradley offers readers his own theory of what unfolded, this being that Monzon, “an angry, illiterate man consumed by petty jealousies,” flew into a rage when he realized both how far he’d fallen and that Muniz would never reconcile with him. Based on the autopsy reports, it’s a credible hypothesis.

Towards the end of the book, Stradley brings the story up to date, summarizing a thirteen-part biopic entitled Monzon that aired in Argentina in 2019 and recently appeared on Netflix, and contemplating the various warring factions in the fighter’s homeland, those being the feminists who vandalize Monzon statues and protest his deification, and the apologists who play down his violent nature while portraying him as a sort of cursed saint. Curiously, this latter group includes Susana Giminez, the glamorous actress who often experienced Monzon’s wrath first hand.

“Monzon’s real legacy,” concludes Stradley, “may be the ongoing tension between those who idolize him and those who wish to forget him.” — Ronnie McCluskey