Maxie Berger: Montreal Royalty

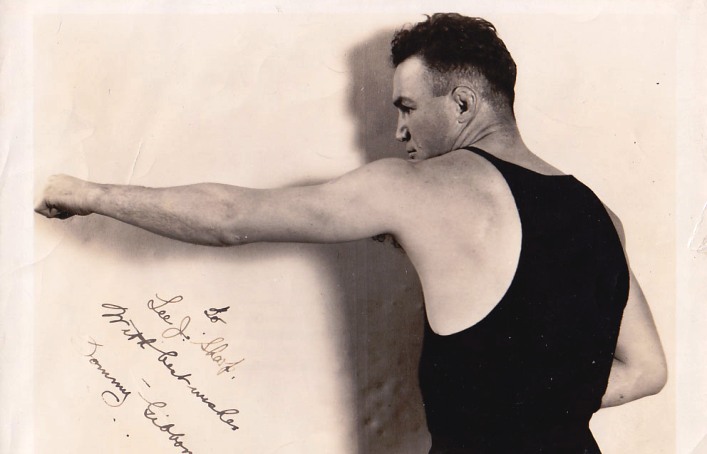

Today, professional Jewish pugilists are as rare as a Shabbat dinner without challah or chicken soup, but believe it or not, there was a time when Jews dominated boxing. According to Mike Silver’s Stars in the Ring: Jewish Champions in the Golden Age of Boxing, there were no fewer than twenty-nine Jewish world champions between 1901 and 1939, which accounts for roughly sixteen percent of the total number of belt-holders in that stretch. In addition to legends like Benny Leonard and Barney Ross, other Jewish battlers with incredible careers include Abe Attell, Jackie “Kid” Berg, Battling Levinsky, Ted “Kid” Lewis, Maxie Rosenbloom, and Lew Tendler. And that’s only the tip of the iceberg.

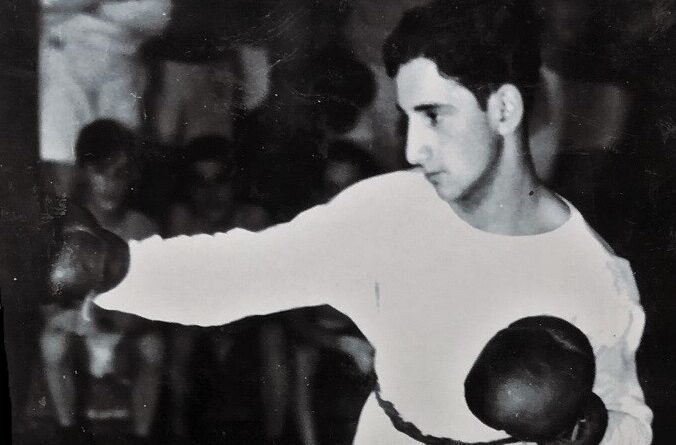

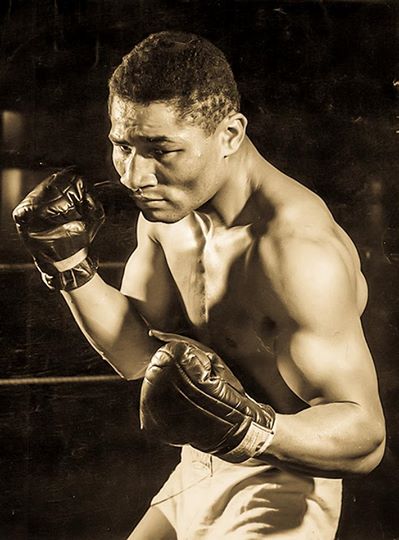

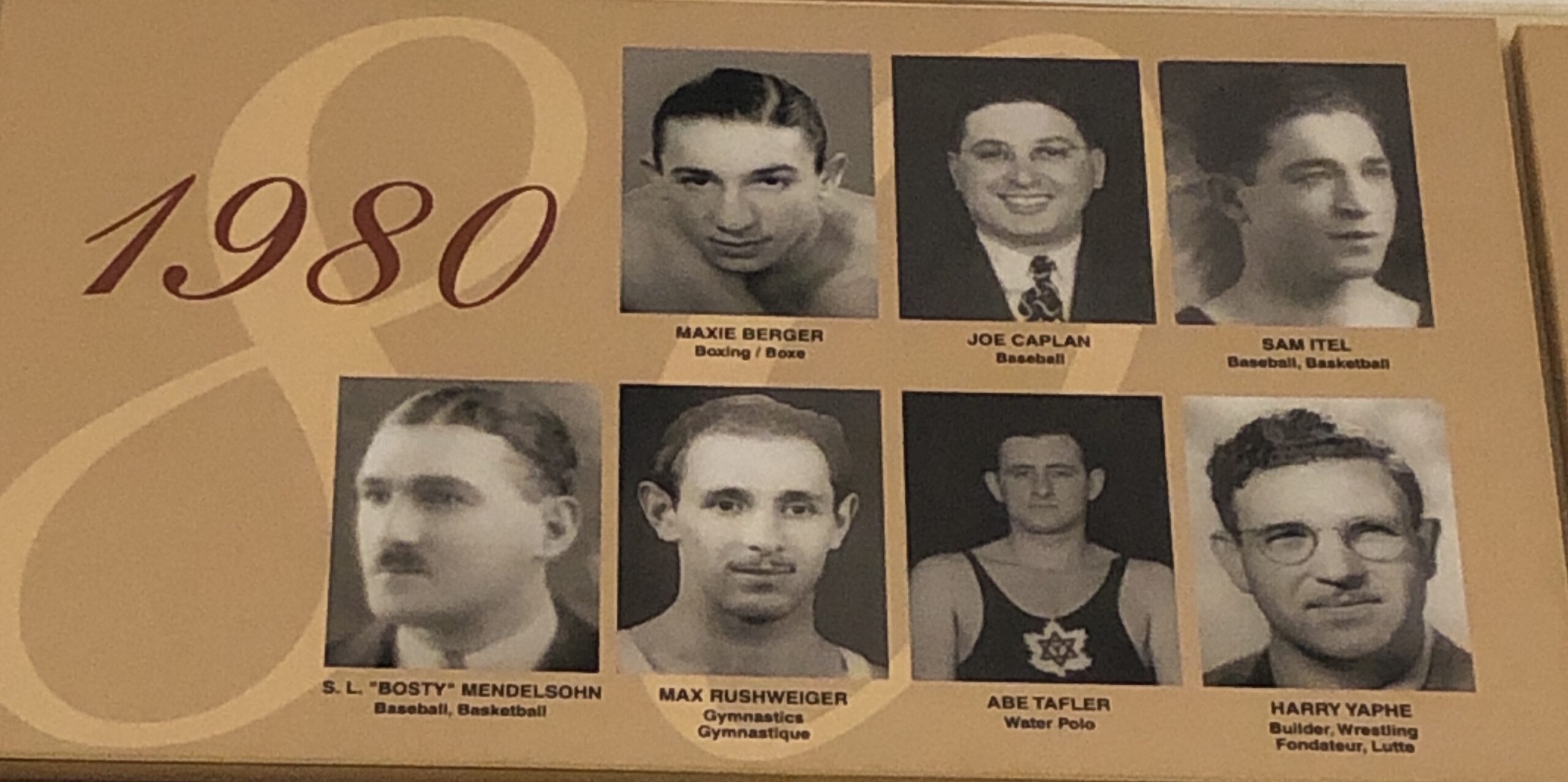

Another important Jewish fighter competing in that same era was Montreal’s own Maxie Berger, undoubtedly one of the finest boxers Canada has ever produced. According to Silver, Berger started boxing at the local Young Men’s Hebrew Association in 1931. It took him only three years to make it to the British Empire Games, at which he won a silver medal for Canada. After posting a 74-16 amateur record, Berger turned pro in 1935 and fought nine of his first ten fights in Montreal. But for a young prizefighter to truly make their name, the U.S. East Coast was where you needed to be, so Berger picked up and moved to Brooklyn, New York, where he fought many of his 131 pro bouts.

Berger was the antithesis of a heavy puncher, scoring only 25 knockouts in 98 pro victories, but he was highly skilled, well-rounded, and a proficient counter-puncher. Prior to Berger’s rematch with Pete Caracciola in October 1936, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle described him as a “swift, sure puncher, very good on the counter and he has a good right-hand uppercut that he uses to advantage in close.” Another article predicted that “Berger would win because he punches more quickly and sharply [and] does untold damage as his opponents move in to be caught by his swift counter punches. It will be a good fight with plenty of action and with Berger drawing plenty of applause for the way he can fend off a punch and answer with swift straight rights to the noggin.” As it happens, Berger and Caracciola fought to a draw on this occasion.

In addition to his formidable skills, Berger has the distinction of having faced a long list of top caliber opponents. He fearlessly took on such legendary fighters as Sugar Ray Robinson, Fritzie Zivic, Beau Jack, Midget Wolgast, Tommy Bell, Ike Williams, and Wesley Ramey. And while he went 3-6 against Hall of Famers, Berger demonstrated his courage, gameness and a desire for greatness by sharing the ring with them.

When Berger squared off with Robinson at Madison Square Garden in February of 1942, Sugar Ray was 27-0 and a top contender for the welterweight title. In fact, Sugar Ray had been scheduled to fight Freddie “Red” Cochrane for the world title, but Cochrane could not arrange sufficient leave from his naval duties. So it was up to Berger to step in and take on one of the hottest prospects in the sport, not to mention a future all-time great. With a record of 74-13-8, and having never been stopped, Berger was seen as a legitimate test for Robinson. As The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported: “In view of Robinson’s impressive record, it is surprising how many smart boxing men predict that Berger may upset the undefeated Harlemite. But Maxie has the boxing style, they say, to nullify Robinson’s aggressive punching tactics.”

Unfortunately for Berger, Robinson showed his class by swiftly and efficiently taking over in just the second round. The New York Times reported that “a long left hook to the jaw dropped Berger in his tracks soon after the second started, and the Bronxonite took a count of six before arising.” After Berger made it to his feet, he “ran into a blizzard of blows, a wicked smashing of rights and lefts to the body and head as Robinson sought frenziedly for a knockout.” Another left hook soon scored a second knockdown, and despite Maxie rising at the count of three, the referee had seen enough and saved Berger from further punishment.

Less than two months after losing to Robinson, Berger took on the legendary Fritzie Zivic in the former welterweight champion’s hometown of Pittsburgh. Against Zivic, Berger got up from two knockdowns in the fourth round and, according to The Oregon Evening Herald, “only the Canadian’s determination appeared to keep him in the battle between the fifth and eighth rounds when rubbery legs made him an easy target.” In that loss to Zivic, and later to the great Beau Jack, Berger proved his mettle and hardiness by lasting the distance. And against men who scored a combined 125 stoppages, that is no small feat.

Although Berger did lose six times to those enshrined in Canastota, he did notch a pair of wins over the Hall of Fame Michigan native Wesley Ramey. According to the Wilkes-Barre Record, “The Montreal Jewish boy who had lost to Ramey twice in the United States, was ahead all the way, dropping his opponent in the third, fourth, and seventh rounds. At the end Ramey could hardly see with his right eye and his face was puffed from continuous drumfire.” Berger would earn another win against Ramey a few months later, equaling their rivalry at two wins apiece.

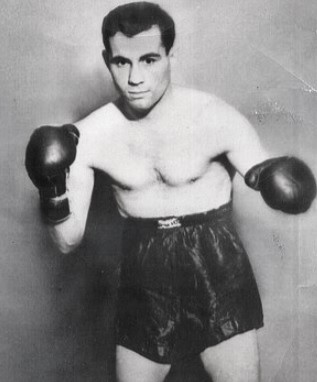

Despite fighting most of his career in the US, Berger established a crosstown rivalry with Dave Castilloux, a fellow Montreal native. Castilloux was a remarkable fighter in his own right, having accumulated a record of 106-20-4 from 1933 to 1948. And like Berger, Castilloux had shared the ring with Ike Williams and Wesley Ramey. In four battles with Castilloux, Berger went 2-2. Berger won the first two contests with Castilloux by decision in 1935 and 1937, both taking place at the Montreal Forum, the second for Canadian lightweight title. In 1941, Castilloux defeated Berger by decision in their third encounter, and repeated the feat in their fourth meeting two months later, that bout for the Canadian welterweight championship.

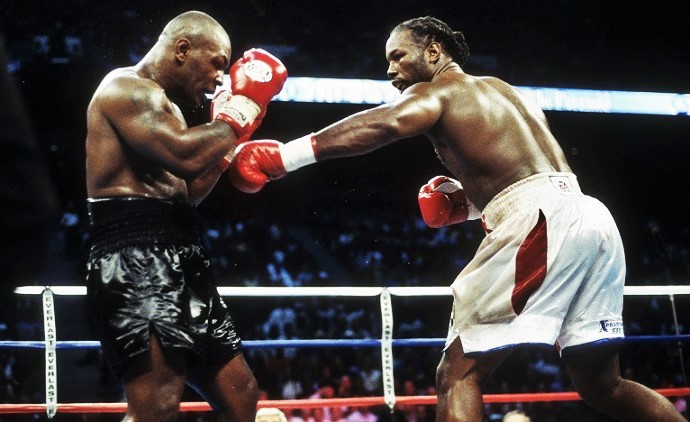

To demonstrate just how highly regarded Berger was among the fight fraternity, consider this tale included in his obituary in the Montreal Gazette in 2000. In 1980, when Roberto Duran took on Sugar Ray Leonard at Montreal’s Olympic Stadium, Berger and his friend Manny Gitnick were in attendance. Gitnick recalls how Leonard’s trainer, the venerable Angelo Dundee, “was so proud to introduce Maxie Berger to Sugar Ray, and he showed Leonard [Berger’s] hands, to show what happens to your hands after years of boxing. Sugar Ray looked at them as if he was looking at a legend. Everybody knew Maxie Berger. He was a class guy.”

As much as Berger accomplished in the ring, he was much more than just a fighter. “He was a good-looking man who dressed well, enjoyed people’s company—particularly the ladies,” recalled his nephew, Sid Singer, following Maxie’s death at 83 in 2000. “He loved a good laugh, a good meal, and a good time. [He] was a kind person, a gentleman, and very humble. He would never take credit for his talent or life. His favorite phrase was, ‘the man upstairs was good to me.'”

Unfortunately, Berger suffered from dementia in his last decade, but he lived a full and prosperous life until then as a warrior and a mensch. And while there were many outstanding Jewish boxers during the first half of the twentieth century, hardly any of them were from Canada, let alone from Montreal. And that is exactly why Maxie Berger should forever be celebrated and remembered as one of Montreal’s most accomplished fight figures. — Jamie Rebner