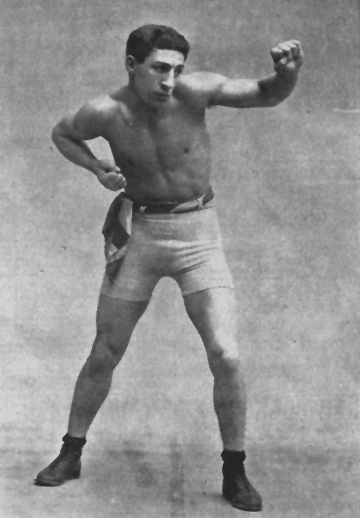

Fight City Legends: The Little Hebrew

“We were Jews living in an Irish neighborhood. You can guess the rest. I used to fight four, five, ten times a day.”

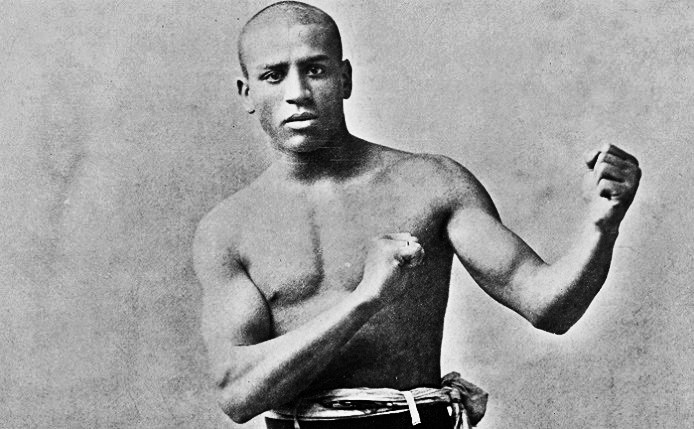

Abraham “Abe” Attell was born in San Francisco in 1884 to a poor family whose patriarch deserted them when Abe was just thirteen. To help put food on the table, young Attell sold newspapers on street corners and on one of those corners was located the famous Mechanics Pavilion, an historic venue which frequently hosted boxing matches. After happening to witness the featherweight title fight between the legendary George “Little Chocolate” Dixon and Solly Smith in 1897, Abe decided that the ring was calling him and he’d try his luck as a prizefighter. Doing so involved obvious risks, but Abe saw the chance to make far more money fighting than he ever could selling papers.

Abe wasn’t the only one in his family to choose pugilism as a profession, as his brothers Monte and Caesar made the same career choice. Their decision to ply their trade in the ring proved a good one as Abe and Monte would later become the first brothers to hold world titles simultaneously.

Attell’s career got underway in 1900 and from the outset he was successful, knocking out all but one of his opponents in his first full year of punching for pay. “When I started I was only sixteen,” recalled Attell years later, “and I thought that the easy way was to knock ’em out. I was a conceited fighter. I thought I could lick anybody. For a long time, I was right.”

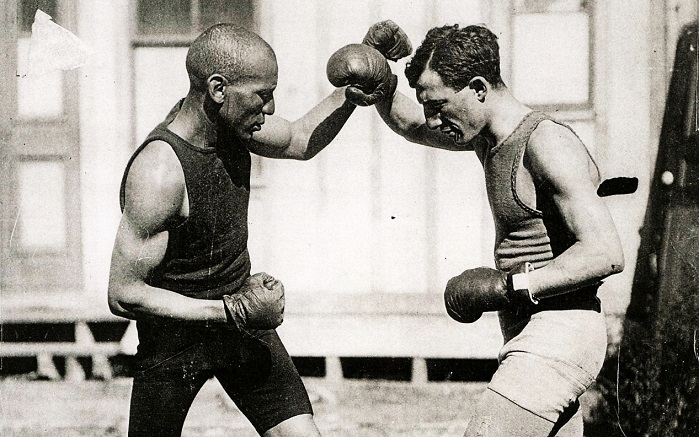

But Attell later transformed his style to one more cerebral and technical by emulating James J. Corbett and Dixon, two of pugilism’s early scientific practitioners. Instead of looking for the knockout, Attell began to weave defense and footwork into his game, making him a much more versatile and unpredictable combatant.

“The light dawned,” recollected Abe. “A fellow could be a prizefighter and not get hurt, provided he was smart enough. I learned that lesson way back in 1900, and I remembered it until I quit boxing in 1915.” And during that fifteen year stretch, Attell built a legacy as one of the greatest featherweights to ever step through the ropes.

Just nine months after Attell’s career commenced he faced the man who had inspired him to become a fighter, taking on the great “Little Chocolate” in Denver in only his 16th pro bout. The relative novice held Dixon to a draw and a rematch two months after yielded the same result. But a week later Attell, who was still four months shy of his eighteenth birthday, battled Dixon a third time and won by fifteen round decision to claim the world featherweight title.

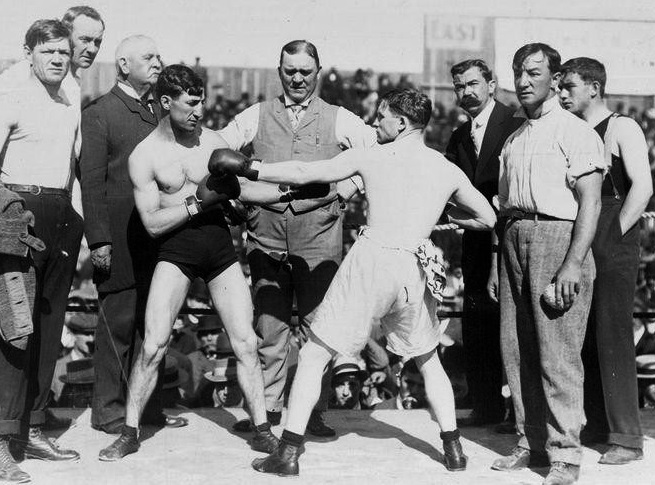

However, in the early twentieth century it was not uncommon for several fighters to simultaneously claim to be the rightful champion in a given division. It was not until 1906, when Attell squared off with Jimmy Walsh, that the undisputed world featherweight championship was at stake. But in the interim Attell had been very active, as top pros always were in those days. Between his win over Dixon and his showdown with Walsh, Abe had answered the bell more than forty times, in the process facing such formidable battlers as Aurelio Herrera, Tommy Sullivan, and Battling Nelson.

Thus Attell wasn’t about to let his chance at total featherweight supremacy slip away as, according to The Los Angeles Times, he “played with [Walsh] as a cat would a mouse [and] when he got through with the milling at the conclusion of the fifteenth round, he did not have a mark on him and was good for many more rounds.”

While the exact number of title defenses registered during Abe’s lengthy reign as featherweight king varies depending on the source, what can never be questioned is the fact he was a fighting champion and always willing to test his elite skills against the fiercest competitors available. In his prime, “The Little Champ” defeated a host of truly excellent pugilists, including all-time greats Pete Herman, Owen Moran, Tommy Sullivan, and Johnny Kilbane.

But Attell was not content with conquering all the available competition in his weight class. In search of more daunting challenges, he regularly moved up to lightweight to take on the top contenders there, including Ad Wolgast, Battling Nelson, Jim Driscoll, and Freddie Welsh, all of whom are enshrined in the Hall of Fame. That he was willing to prove himself against the best, regardless of weight, demonstrates Attell’s fearlessness and why he is rightfully recognized as one of the finest ringmen of all-time.

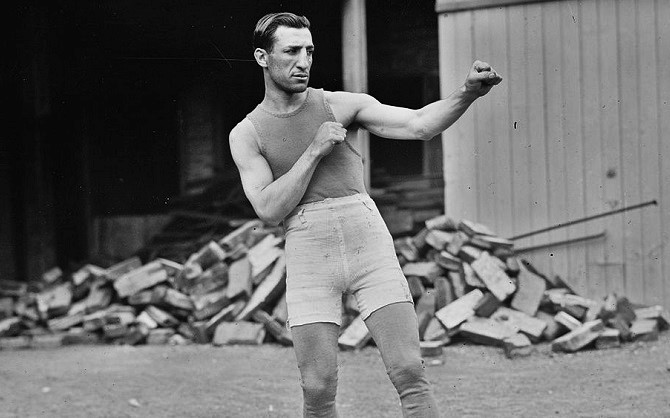

As famed fight scribe Lester Bromberg wrote: “Attell’s natural weight was 117 [but] he gloried in being small. There were instances when he gave away as much as twenty pounds. But he liked being ‘The Little Champ’ … to him there was added honor to it.”

Legendary boxing promoter Tex Rickard stated that Abe Attell was the greatest boxer he had ever seen. Author Allen Bodner asserts Attell is second only to the legendary Benny Leonard in the pantheon of great Jewish boxers. No serious list of the all-time best featherweights can omit his name and most put him in the top five, shoulder-to-shoulder with fellow immortals Willie Pep and Henry Armstrong.

However, by 1912 the frenetic pace of Abe’s career had caught up to him and he lost his world title by decision in a rematch with Kilbane. A report from the Los Angeles Herald states that “Attell did not put up his usual classy exhibition and failed to show within 50 percent of the same great boxer who so frequently drew with Owen Moran and defeated Ad Wolgast and other great fighters.”

Notably, during round sixteen of this bout, the referee had to wipe an unknown substance from Attell’s body. Kilbane insisted it was chloroform intended to make him groggy; Attell refuted the accusation, insisting the substance was cocoa butter. Regardless of the veracity of Kilbane’s accusation, this was far from the only time Attell was suspected of bending the rules. The fact is, the tale of “The Little Hebrew” cannot be complete without mentioning his shady side.

At one point, the New York State Athletic Commission even banned Attell from competing for six months because he had barely put forth an offensive effort against one Valentine Braunheim, aka “Knockout Brown,” in January of 1912. Attell’s reputation preceded him and his reluctance to fight convinced all that the fix was in. Abe insisted that his performance was affected by an injury to his thumb for which cocaine had been injected, but years later he admitted not always giving forth his best effort for the purposes of securing a bigger payday in a prospective rematch.

But of course the most nefarious scheme in which Attell was allegedly involved came after his career had ended in 1917. As a member of gangster Arnold Rothstein’s entourage, Abe was accused of helping to facilitate one of the biggest scandals in sports history, the famous “Black Sox Scandal” of 1919 when eight players on the Chicago White Sox allegedly threw the World Series against the Cincinnati Reds. Attell was never brought to trial as he managed to convince a New York jury that it was all a case of mistaken identity and that he was not the same Abe Attell that the Chicago Grand Jury was after. But even if he was never convicted, the mere association adds another black mark to Attell’s reputation.

Eventually Abe put the scandal behind him and settled down, opening a popular tavern in New York’s East Side. And he never strayed too far from his sport of choice, often attending fight cards at Madison Square Garden. Abe would spend his final years in a nursing home before passing away at age 85 in 1970.

Despite all of Attell’s antics and the accusations that followed his career, nothing can overshadow his undeniable ring greatness and accomplishments. Abe Attell, a true ring legend, built a boxing legacy that will forever stand the test of time, having competed in over 150 pro bouts. Not bad for a poor Jewish kid who used to sell papers on the corner just to get by. — Jamie Rebner

Great read Jamie.

Thanks Ray, glad you enjoyed it!