July 15, 1931: Chocolate vs Bass

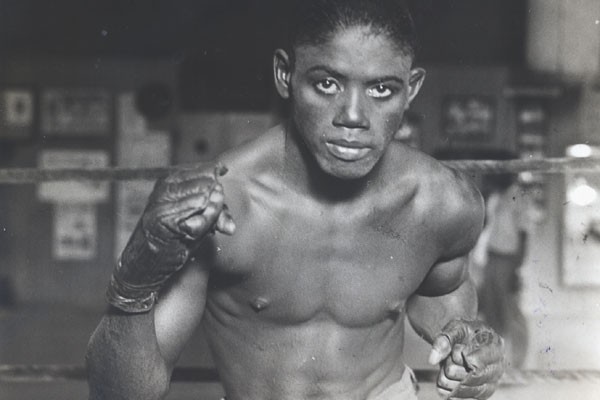

Throughout boxing history, world titles have assumed various levels of worth, some about as valuable as your proverbial wooden nickel. It’s a process unlikely to ever stop, as different sanctioning bodies and incarnations of championships are always being created and destroyed, but if naught else the belts do signify some kind of achievement and often function as a means to an end. And indeed a world title belt not universally recognized triggered a wave of patriotism and euphoria in Cuba on behalf of Eligio Sardiñas, aka the great “Kid Chocolate,” the island nation’s first world champion.

A 160-0 amateur record, as reported by Chocolate’s manager Luis “Pincho” Gutierrez, was likely fudged, but no one could deny “The Keed” seemed destined for stardom. The former newsboy brought his entertaining ring style to New York in 1928, along with his stablemate Black Bill, and after only ten fights, Kid Chocolate caught on as a major attraction. He stayed that way as he went on a 61-3-1 tear, putting himself in line for a chance to face Benny Bass, holder of the National Boxing Association’s super featherweight title, a championship acknowledged by some, but not all.

The losses on Chocolate’s ledger came at the hands of Jack “Kid” Berg, Fidel LaBarba and Bat Battalino, and were all forgivable, if not disputed. Still, the Cuban’s popularity caught up with him, as noted by Kansas City editor Edward Cochrane: “About a year ago [Chocolate] was rated by the leading fistic experts of two continents as the best featherweight in the world despite the fact that he did not hold the title. Then he went the way of all boxers. He decided he could do Broadway at night and retain his fighting form but he found that he could not.”

A title shot loss against New York’s featherweight champion Battalino perhaps reflected the cost of such high living. The Kid then moved up to super featherweight, a division still struggling for legitimacy a decade after its semi-formal inception.

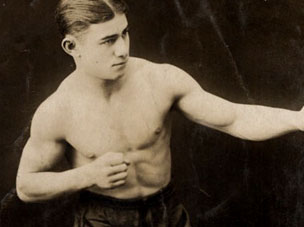

Bass was no unknown himself, though despite his history of being warned and even disqualified for low blows, Bass was more soft spoken than The Kid. But his record of 105-15-3 proved his toughness and experience, even if he had trouble winning the important ones. Losing to Tony Canzoneri was understandable, but Pete Nebo, Eddie Shea and Mike Dundee were all beatable opponents. Unfortunately, Bass often underperformed, starting with losing a spot on the 1920 U.S. Olympic team in the semi-finals of the Amateur Athletic Union games. (He was sent packing by William Cohan, who would then be defeated by Frankie Genaro, the eventual gold medalist.)

After having picked up a vacant featherweight belt, which he then lost to Canzoneri, Bass won the NBA junior lightweight title with a two round destruction of Tod Morgan in 1929. But then the New York State Athletic Commission moved to abolish all junior or supplemental weight classes and ceased to recognize Bass as a champion at 130. It was another hit to a division largely considered superfluous.

All through 1930 and the first half of 1931, Bass could not consistently prevail over good fighters, but due to the screwy rule in some jurisdictions stating that champions needed to be stopped to lose a belt, he managed to hold on to his NBA title and his defense against the Cuban was set for Shibe Park in Philadelphia.

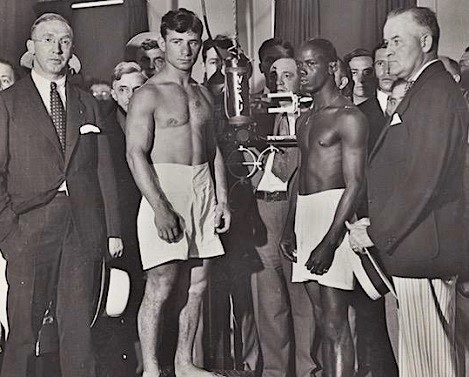

In training, Bass pitched hay at his Berlin, N.J. farm between gym sessions, while Chocolate worked at the headquarters of George Godfrey just outside of Philadelphia. The Kid even wrestled with Godfrey, who outweighed him by 100 pounds or more, after sessions with his usual sparring partner, Nick Florio. The irony of Kid Chocolate grappling with a fighter named after George “Old Chocolate” Godfrey aside, the exercise probably did little to enhance his boxing skills. It did, however, keep The Kid in great shape, as he came into the match weighing well below the super featherweight limit.

Following an intense opening round, Bass returned to his corner complaining that the vision in his left eye was quickly diminishing. He would later state he had been thumbed, and in round two the same eye opened up, spilling copious amounts of blood. From then on, The Kid set himself to annex the belt on cuts, as he mercilessly pecked away at the bad eye. A United News report out of Pittsburgh read, “Bass was bewildered by Chocolate’s boxing skill and frequently swung all the way around in attempts to hit his opponent. On other occasions he wound up with his back to the Cuban.”

The champion’s usually trusty left hook was easily dodged or taken on Chocolate’s gloves, though Bass sometimes found The Kid’s body, where he was said to be weak. But the difference in speed and sharpness was a killer, and through rounds five and six the challenger dished out welts and whips galore. Bass was fading quickly and The Kid sensed a world title within his grasp. The end came in round seven.

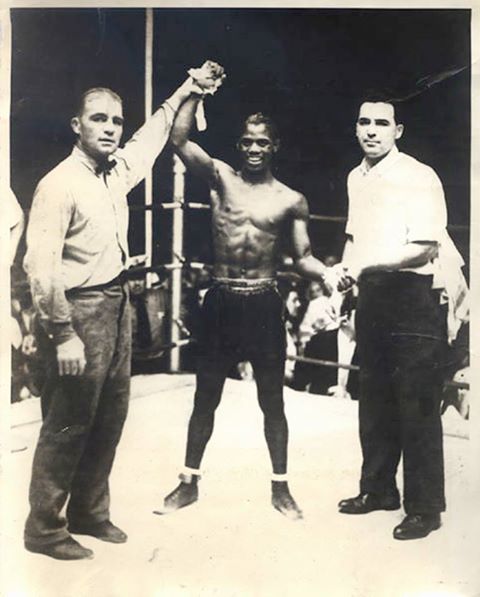

“[Bass] was in a battered condition when Referee Leo Houck ordered the bout stopped,” reported The New York Times. “His left eye was closed and bleeding badly, while he also had a split under his chin. On the other hand, Chocolate appeared virtually unharmed as the battle ended. To celebrate winning the title the Cuban danced for joy in his corner as the crowd set up a roar of acclaim.”

The Kid had every right to celebrate. After all, blindness had already retired Black Bill, Cuba’s other championship hope, and with the victory Kid Chocolate became Cuba’s first world titlist and an overnight national hero. — Patrick Connor

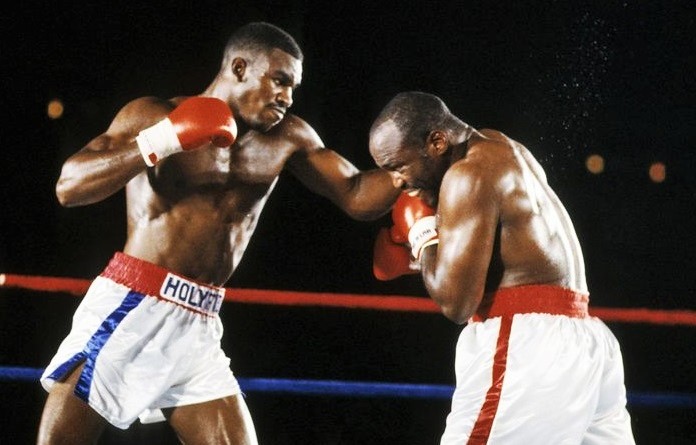

Who is the Fighter in the video with Kid Chocolate? I’m Benny Bass’s Great Grandson.