The Napoleon Of The Prize Ring

Napoleon, war-master, was a terror to his foes,

A general of generals, as everybody knows;

And Jack McAuliffe, lightweight king, who many battles won,

Was tagged by his admirers: “The Ring Napoleon!”

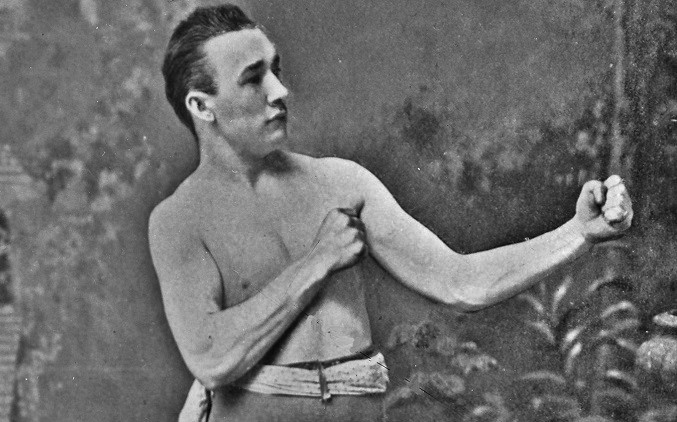

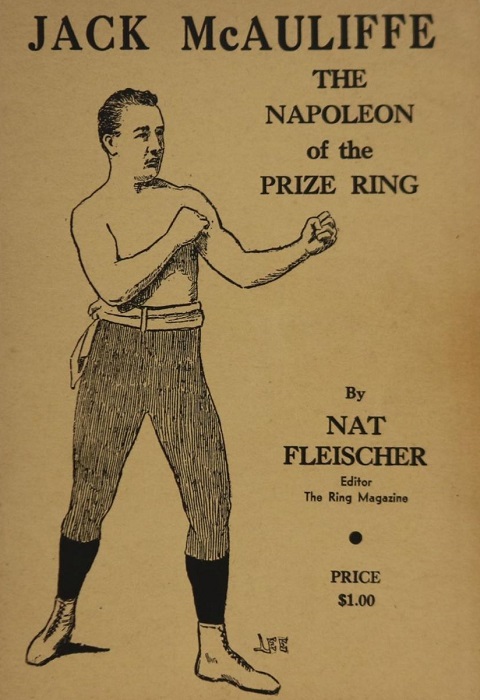

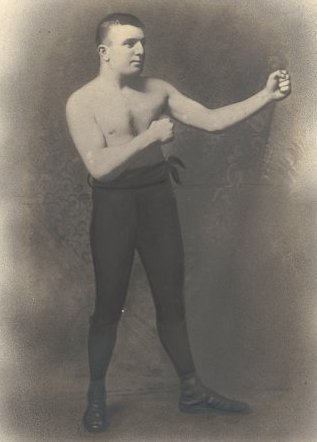

Nat Fleischer’s opening poem in his 1944 biography on Jack McAuliffe ends of course with a little caveat: unlike Bonaparte, McAuliffe never did “meet his Waterloo.” Not even after twelve years as a professional, seven of which were spent as lightweight champion, did Jack ever meet his match. Despite engaging in some of the most brutal affairs ever witnessed in the ring, McAuliffe became one of the first post-bareknuckle champions to retire undefeated.

Jack McAuliffe was born March 24th, 1866 in Cork, Ireland, a child of the Emerald Isle. He wouldn’t arrive on America’s shore until 1870, when his father, who had served in the US Army in the American Indian wars, finally had enough money to bring his family overseas to Bangor, Maine.

Not quite your exemplary student, McAuliffe was often at the receiving end of his teacher’s cane. He also found himself in many street fights with his peers, and Jack quickly developed a reputation for his scrappiness. In fact, McAuliffe eventually became one of the most revered fighters among the sailors that inhabited the city of Bangor and before he had turned 15-years-old he earned his first purse when he knocked out a much larger and older British sailor for a winner-take-all sum of eight dollars.

Not long after the McAuliffe family moved to the Williamsburg neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York, home to many Irish-American immigrants. As he had in Bangor, Jack made a name for himself with his fists, successfully deposing the neighborhood kingpin Paddy Garrity after some fierce confrontations. “I’ve had some professional glove fights in which I took less punishment than in some of those hot mixes with Paddy Garrity,” recalled McAuliffe, who shortly after that triumph struck one of his most important alliances, that being with neighbor and fellow Celt, Jack Dempsey, “The Nonpareil.”

Dempsey was four years older than McAuliffe and in an interview with Fleischer the latter gave credit to Dempsey for teaching him all he knew about ringcraft. They worked together in an improvised gym in the Fourteenth Ward of New York City, and McAuliffe would follow his friend and mentor into the professional game soon enough. But first, McAuliffe took a year to get some seasoning in the amateur game.

As Fleischer notes in his biography, amateur boxing in the early 1880s was something very different from our conceptions of it today. There was little regulation or supervision of any kind and the matches, which often involved an unlimited number of rounds, were contested for pride more than anything else. While these fights may have observed the Marquis of Queensberry rules, in all other regards they were a cheap bloodletting for the fans.

In 1884 McAuliffe entered an amateur tournament staged by the future manager of John L. Sullivan, Billy Madden. He was drastically out-sized by the other combatants as the tournament weight limit was 140 pounds while McAuliffe weighed roughly 112. Nevertheless, after a series of hard-fought bouts Jack emerged as the winner of the competition and for the next year he dominated in amateur tournaments before turning pro under the tutelage of Madden and Dempsey.

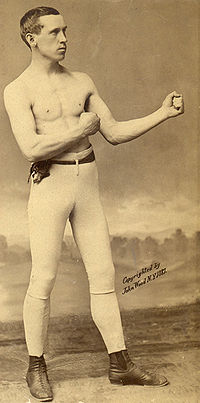

Despite the Nonpareil’s efforts to hand off to his pal the lightweight crown he had relinquished upon his move up to middleweight, this was a time when titles had to be won in the ring (sorry, Devin Haney). As a result, Madden had McAuliffe embark on the kind of “taking all comers” pugilistic tour that would prove to be John L. Sullivan’s ticket to success when the “Boston Strong Boy” could “lick any sonofabitch in the house.”

In McAuliffe’s case, one of those “sonofabitches” was Bull McCarthy, a longshoreman from Philadelphia who had built a high reputation for himself in his dockside scraps. McAuliffe vs McCarthy proved a highly volatile situation, as the venue was packed with stevedores who had bet heavily on McCarthy.

But when McAuliffe knocked McCarthy out cold, it was not the longshoremen who made a fuss, but McCarthy’s father, who got up and screamed, “Ye will hurt my boy, ye spalpeen!” The distraught father then flung a chair onto the stage where the fight had taken place, striking McAuliffe and causing him to collapse alongside his fallen opponent just as the curtain came down and the crowd went wild. Despite their lost wages, the longshoremen got their entertainment for the evening, and luckily for McAuliffe and Madden, Jack was not badly injured by the chair. Such was the fight game back in 1886.

Another notable stop on this “Tour de Brutes” involved a rematch with Jack Hooper which took place outdoors and during weather that was so cold that the two pugilists were fighting not only to win, but to avoid hypothermia. Jack finally knocked Hooper out in round seventeen, perhaps saving the two from serious illness. “It was a miracle that any of us survived!” said McAuliffe who was nearly frost-bitten from the freezing cold.

Despite McAuliffe’s success on the tour, his manager Billy Madden was more preoccupied with his young British heavyweight protégé, Charlie Mitchell, a circumstance to which Jack grew impatient. Madden simply didn’t have enough time to invest in McAuliffe, and as a result, Jack became his own manager. (Fleischer notes in his book how by the 1930’s and 40’s managers could oversee the careers of several boxers at a time. One wonders what he would think of today’s massive fight stables.)

Now a free agent, McAuliffe challenged Billy Frazier, the Harvard University boxing coach who was regarded as one of the best lightweights in the country. Upon arriving in Boston, McAuliffe played a few mind games on Frazier and his backer, Patsy Sheppard, feigning that he was too fearful to get in the ring against the Harvard instructor. Sheppard and Frazier took the bait, each giving Jack $10 to stay the course and take part in a fight scheduled for three days later. Jack scored a knockout in round twenty-one to secure recognition as the lightweight champion of America.

Less than three months later, McAuliffe fought for the “world” lightweight title against revered Canadian lightweight champion, Harry Gilmore, in what was regarded at the time as one of the most exciting encounters ever witnessed. The bout was confined to a Lawrence, Massachusetts blacksmith shop that housed a ring enclosed on three sides by ropes and on the fourth by a brick wall. As one might expect, that wall proved a hazard with McAuliffe’s thumb being broken and Gilmore possibly suffering a fractured skull, but that didn’t prevent the spectators from enjoying a ferocious battle ending with a knockout for the American in round twenty-eight.

While by this time most regarded McAuliffe as the world champion, there was one notable pugilist who objected to that notion, a bricklayer from Birmingham, England by the name of Jem Carney. Carney was the British lightweight titlist and highly feared on both sides of the Atlantic and he got his chance to prove himself the true world champion on November 16th, 1887. Despite the match garnering international attention, McAuliffe and Carney squared off in a dimly lit Massachusetts barn in order to avoid interference from local law enforcement. The result was a battle for the ages.

McAuliffe and Carney duked it out for seventy-four tumultuous and foul-filled rounds, the battle lasting some five hours, before the ring was overrun by a wild mob, forcing referee Frank Stevenson to rule the contest a draw. There were reports claiming that McAuliffe was being outclassed by Carney throughout, but this was hotly disputed by those present, including ringside reporter A.D. Phillips whom Fleischer later interviewed. What was not disputed was that McAuliffe was fading badly against the ever-pressing Brit by the time the match finally ended.

“From a scientific standpoint, Carney was outclassed, but he seemed to have it on McAuliffe in punishing power,” said Phillips, who recalled many details from the five hour scrap. However, by the sixtieth round, Phillips recounts that it was all downhill for McAuliffe, who was nearly knocked out in both the 70th and 74th rounds before the bout was stopped.

Those sponsoring the event were worried the raucous, weapon-bearing mob would attract the attention of the police, which led to the bout being called before McAuliffe could be knocked out. There was plenty of controversy on both sides, with Carney’s backers claiming the referee robbed their man of the fight to support American betting interests, and McAuliffe’s backers claiming Carney’s fouls, including the illegal use of his knees, should have resulted in his disqualification. Despite 74 rounds of grueling combat, a universally recognized lightweight champion was not crowned, and McAuliffe and Carney would never meet in the ring again.

McAuliffe enjoyed success for the next four years, with perhaps his toughest rival being Billy “The Streator Cyclone” Myer. Their first match was another unsatisfying draw, but the two would fight again on perhaps one of the best fight cards in boxing history, the first match of a three day carnival of champions that also featured John L. Sullivan vs James J. Corbett for the heavyweight championship, and George Dixon vs Jack Skelly for the bantamweight title. History would be made at the New Orleans Olympic Club when Corbett lifted the world title with a knockout of Sullivan, but McAuliffe also turned in one of his best performances.

Unlike their first affair, Myer took the fight to the champion straight away. The first four rounds featured tremendous back-and-forth action as the two exchanged knockdowns, with McAuliffe decking Myer in the second round, and both hitting the deck in a tumultuous round four. McAuliffe persevered and got the knockout victory in the fifteenth round, to which he celebrated to the tune of a half-dozen beers in his corner with one of his seconds, the great Joe Choynski.

“I think I earned that drink, Joe,” said McAuliffe in exultation. McAuliffe was also the chief second for John L. Sullivan in his title defense against Corbett two days later and he ordered his close friend Dick Roche to place his entire $10,000 purse on his man to retain the title, some three hundred thousand smackers in today’s money. Fortunately for the champion, Roche wisely held off on placing that wager and later returned McAuliffe’s purse.

“You see, after you passed me the dough, I got to thinking, and went to have a chat with Corbett’s handler, Billy Delaney,” Roche told McAuliffe. “After I heard Billy’s speil, I was convinced that Sullivan was going to lose.”

The knockout over Myer was not only the pinnacle of McAuliffe’s career, but also the beginning of his decline. In his last significant bout in August 1894, McAuliffe, who was regarded as one of the most scientific boxers of his era, received a ten round boxing lesson from defensive wizard Young Griffo, who made the once-great McAuliffe miss early and often. McAuliffe received what most present regarded as a gift decision, but while many in the crowd booed the outcome, they soon enough acknowledged the legendary career of Jack McAuliffe, as he was now to retire unbeaten.

Unlike other great champions who stuck in the fight game for far too long, McAuliffe knew when to call it quits. A stubborn gambler who lost most of his earnings after his career had ended, McAuliffe refused to step out of retirement to make a buck, even when promised ten thousand dollars to face British champion Dick Burge. “I know how much I have slipped,” said McAuliffe. “I’m not going in a ring to be licked by Burge or anyone else and have my friends lose money on me. I’ve quit with a clean record.”

And with that, McAuliffe holds the rare distinction of being one of the few champions to retire unbeaten. McAuliffe was kneed, pivot punched, forced to box in freezing weather, and engaged in some of the most violent and grueling contests in ring history, but in every circumstance he was crafty and gutsy enough to find a way to circumvent defeat. For his achievements and artistry inside the ring, Jack McAuliffe stands not only as a pioneer of boxing technique but also as the proper starting point for the lightweight lineage. — Alden Chodash