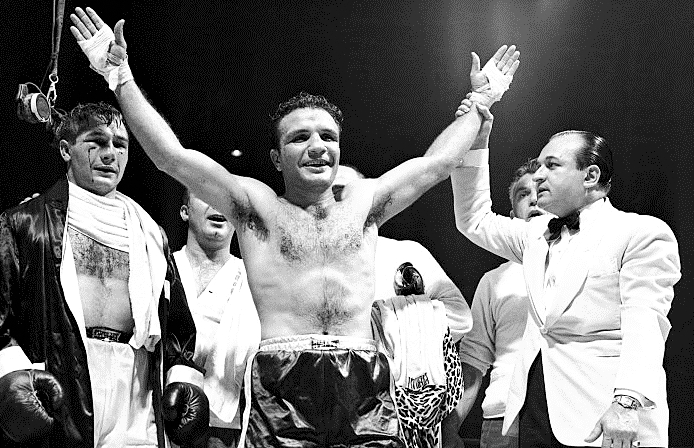

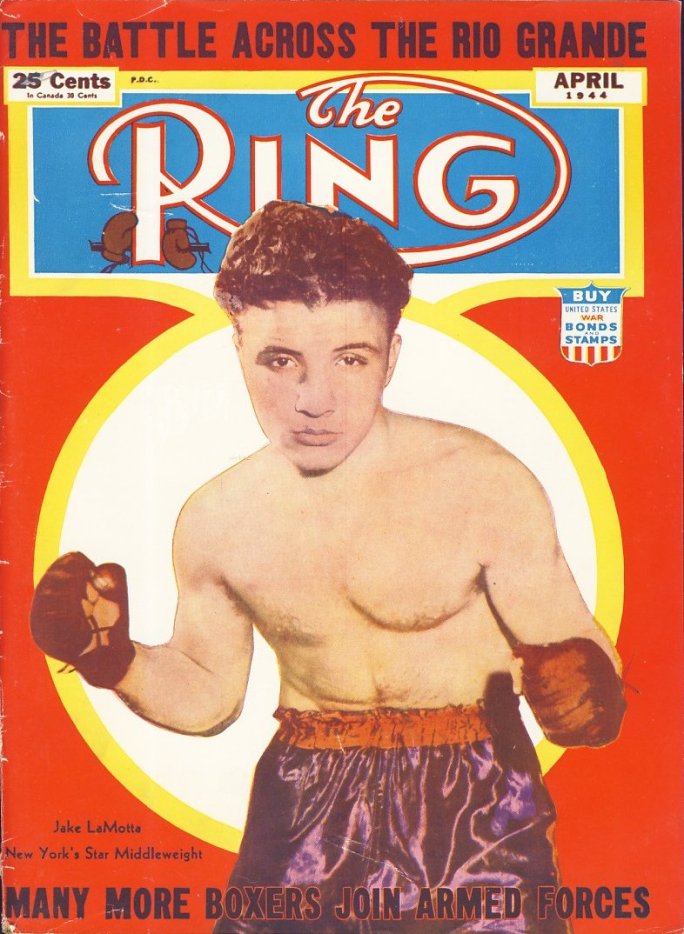

Jake LaMotta: 1922-2017

Jake LaMotta, who died yesterday from complications due to pneumonia, was boxing’s oldest living former champion and a direct link to the “Golden Age” of prizefighting, a time when boxing gyms and fight clubs proliferated in every major city, when every division boasted a plethora of warriors worthy of the Hall of Fame, and when the best fought the best, and on a frequent basis.

Of course, there was also the dark side: the influence of organized crime and the exclusion of boxers from title shots and big money because they were Black, or because they wouldn’t play ball with the mafia. LaMotta knew first-hand about such things. He only received a chance at the world middleweight title after he agreed to put some extra money in the pockets of hoodlums by taking a dive against Billy Fox.

LaMotta’s career is the stuff of legends and there is no doubt he belongs in any conversation about the greatest middleweights of all-time. He has his detractors who point out Jake’s tendency to seek out matches with welterweights, but no one can argue that Jake bested a long list of Hall of Fame fighters. It includes Marcel Cerdan, Fritzie Zivic, Tommy Bell, Holman Williams, George Costner, Bob Satterfield, Tony Janiro and, of course, the name to which LaMotta’s will forever be linked, Sugar Ray Robinson.

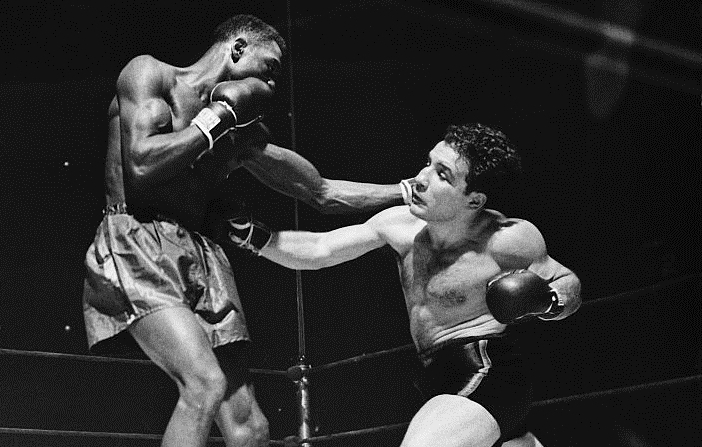

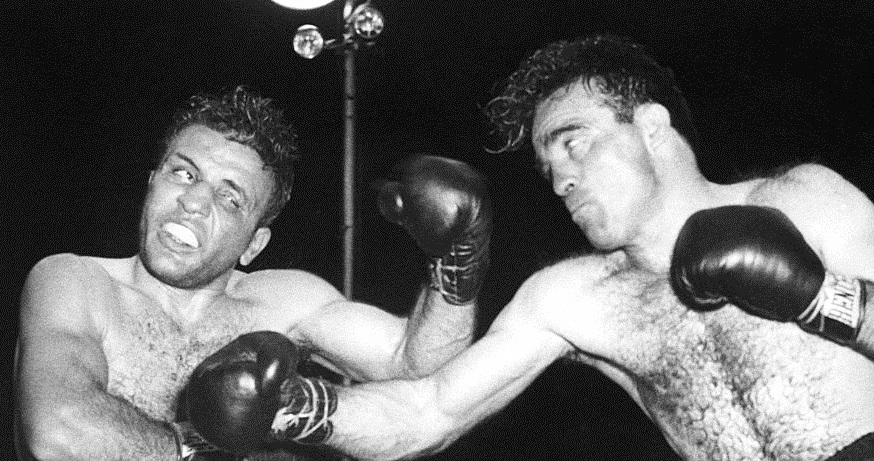

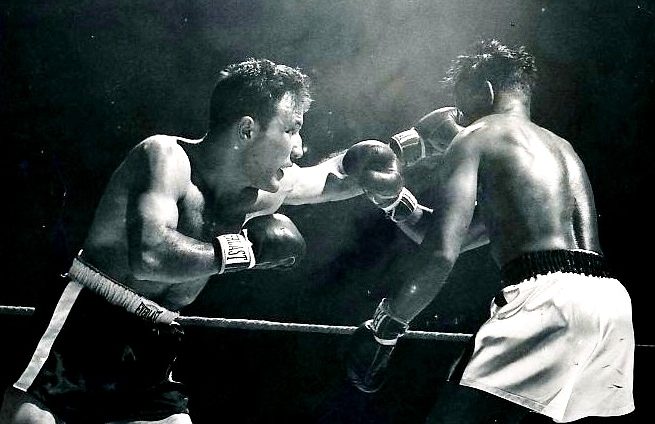

LaMotta is famed both for his aggressive, swarming style and his incredible durability. He stands as one of the all-time great “catchers,” a fighter who tests his opponent’s power and happily takes blows in order to land his own. But in addition to being an aggressive slugger, LaMotta could be crafty. He knew how to roll with punches and he was also skilled at “playing possum,” pretending to be hurt and thus duping his opponents into punching themselves out, or leaving openings which LaMotta could exploit.

The young LaMotta grew up in the Bronx in New York City and had his share of run-ins with the police for petty crime before he got serious about his ring career. He was encouraged by his father to box and he turned pro in 1941 at the age of 19, fighting 23 times in his first full year of action. He quickly became a popular performer and was viewed as one of the most promising prospects around, as well as a hot ticket. His rivalry with fellow up-and-comer Ray Robinson began in October of 1942 and the following year he gave the great Sugar Ray his first defeat.

LaMotta maintained a hectic pace, competing no fewer than a dozen times per year, amassing a huge number of rounds against some of the best fighters in the game, but, to his increasing frustration, getting no closer to a chance at the world title. In 1946, despite the fact he was arguably the most deserving contender in the middleweight division, champion Tony Zale instead engaged in a remarkable three fight series with Rocky Graziano and LaMotta was effectively frozen out of the title picture. After regaining the title from Graziano, Zale again took a pass on Jake to instead fight France’s Marcel Cerdan, who stopped “The Man Of Steel” in 12 rounds.

In November of 1947 LaMotta suffered an upset defeat to Billy Fox which immediately came under suspicion; LaMotta’s claim at the time was that he was nursing a training injury. But then seven months later he challenged Cerdan for the middleweight championship of the world. In the first round Jake opened up with a two-fisted attack and when Cerdan attempted to clinch LaMotta threw him to the floor. The fall injured Cerdan’s left shoulder and he was reduced to slugging it out with only one good hand which led to Cerdan’s corner stopping the fight after round nine. Four months later Cerdan was killed when the plane bringing him back to America for the rematch crashed in the Azores.

The highlight of LaMotta’s reign as champion was his dramatic battle with Laurent Dauthuille in September of 1950. Well behind on points, he staged a desperate rally in the final round to knock out the challenger with just 13 seconds left in the match. By this point LaMotta was starting to slow down and in his very next bout he lost his world title when Robinson stopped him in the famous “St. Valentine’s Massacre,” a match for which Jake was a solid 3-to-1 underdog. Robinson dealt LaMotta a horrific battering but, famously, “The Bronx Bull” could boast that in six battles with the great Sugar Ray he had never once visited the canvas. The Billy Fox match aside, this was the first time that Jake LaMotta had failed to go the distance.

After that, Jake’s career wound down. He had engaged in close to 90 rough and tumble battles in ten years and the wear and tear was starting to show. He appeared to be finished after he was decked for the first time in his career by light heavyweight Danny Nardico and stopped in seven rounds. He came back in 1954 to do battle three more times before retiring for good. His record stands at 83-19-4 with 30 knockouts.

Following his retirement, LaMotta owned and managed bars and nightclubs and tried his hand at acting. An underaged girl was found to be taking on paying clients in one of his establishments, leading to a six-month prison sentence for abetting prostitution in 1958. Previous to that, LaMotta also attracted attention when he testified at a U.S. Senate subcommittee investigating the influence of organized crime in professional boxing. It was then that Jake confessed what some had suspected, that he had taken a dive against Fox in exchange for the guarantee of a title shot.

In 1970 LaMotta published his memoir, Raging Bull: My Story. The book described his criminal exploits as a youngster, his time in prison, his turbulent personal life, and his boxing career. It also detailed his ultimately unsuccessful struggles to avoid dealing with the mafia in his quest for a chance at the world title. The book attracted the attention of Robert De Niro and Martin Scorcese who would adapt it and turn it into the 1980 Oscar-winning movie Raging Bull. In 2007 The American Film Institute ranked it behind only Citizen Kane, The Godfather and Casablanca on its list of the all-time greatest films.

The success of the movie, as well as LaMotta’s own exuberant personality and countless public appearances, sustained his status as a larger-than-life figure and a sports celebrity. And while his career is largely defined by his amazing six fight rivalry with Sugar Ray Robinson, his life outside the ring only bolstered his image as one of boxing’s “bad boys” from an era when boxing itself was an even rougher and meaner business than it is today. Jake LaMotta is a legitimate ring legend and as long as there are fight cards and boxing gyms and prizefighters, “The Bronx Bull” will never be forgotten.

— Robert Portis