Feb. 28, 1973: Napoles vs Lopez II

They call boxing the cruelest sport for a number of reasons, one of them being that no matter how talented or dedicated a boxer is, his success ultimately depends on whether he has the good luck to avoid his superior. There are as many examples of this as there are capable fighters who compete at the elite level of their difficult profession; in other words, countless.

To cite just a few: Lew Tendler was a vastly talented southpaw who more than held his own in perhaps the best lightweight division in history, but the man between him and a world title was the even more talented Benny Leonard. “Bad” Bennie Briscoe is considered one of the best ever at 160 pounds, but it was his misfortune to strive for the top of the middleweight mountain at the same time as Rodrigo Valdes, Emile Griffith, Carlos Monzon and Marvelous Marvin Hagler. Ken Norton might have reached the heavyweight pinnacle, but Muhammad Ali, George Foreman and Larry Holmes all got in the way.

Similarly, Ernie “Indian Red” Lopez had the stuff to be a world champ, but there was just one major problem; its name was José Napoles.

Any serious discussion of the truly great welterweight champions must include the legendary “Mantequilla,” as gifted a pugilist as boxing has ever seen. His nickname means “butter” in Spanish and this referred to the smoothness of his moves and his relaxed demeanour in the ring, but the moniker belies the fact Napoles possessed crushing power and ruthless finishing instincts.

Napoles learned his trade and began his career in Cuba, but he was forced to flee his native country when the Castro regime banned professional boxing. He settled in Mexico where the locals adopted him as one of their own. Through the 1960’s he campaigned as a lightweight and junior-welter, but his skills and power were such he had to move up to welterweight to get fights. He finally received a title shot in 1969 and would go on to win fourteen championship bouts before losses to Carlos Monzon and John Stracey prompted him to retire.

Ernie Lopez, along with fellow gifted contenders Hedgemon Lewis and Armando Muñíz, all tried and failed to dethrone Napoles. The three also shared the experience of giving Napoles tough battles the first time around, before being dominated in the subsequent rematch. (However, it must be noted that the first meeting between Muniz and Napoles was not merely a highly competitive fight. In that instance, Napoles was shamelessly defended by the referee who, instead of granting Muniz the TKO victory he deserved, blamed Napoles’ cuts on headbutts and awarded the fight to the champion.)

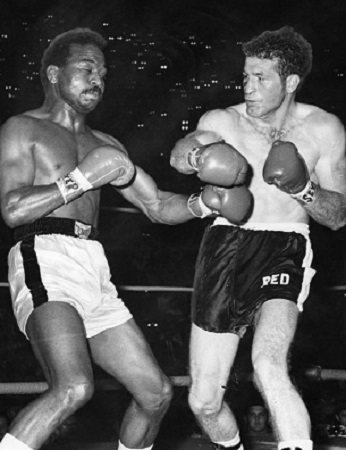

Lopez and Napoles first met in February of 1970. “Mantequilla” clearly won, scoring three knockdowns and forcing a stoppage in the final round, but Lopez gave a decent account of himself against a dominant champion. In the months that followed he stayed active and maintained his position as one of the top contenders, a rematch scheduled two years later. However, few gave Lopez a serious chance of reversing the outcome of their first bout. While he had hung tough with Napoles for almost fifteen full rounds, the deciding difference between the two men was obvious: raw power.

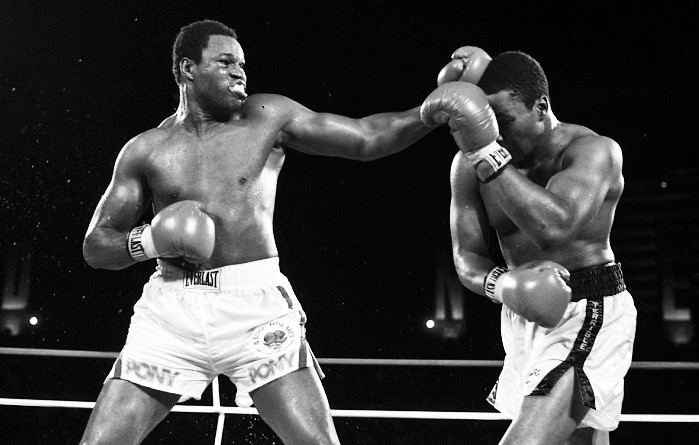

Napoles vs Lopez II was highly competitive over the first four rounds. Lopez boxed carefully, keeping his hands up and using his jab to good effect, opening up cuts in the second and third. Keeping the fight in the center of the ring, the challenger worked to maintain distance while landing solid right hands to Napoles’ body. In the fifth the action intensified with the Cuban exile getting in some solid counter left hooks. Lopez struck with a big right hand to the chin, but the punch only prompted Napoles to pick up the pace. He hurt Lopez with a pair of thunderous hooks and the battlers traded toe-to-toe until the end of the round.

In round six Lopez tried to reassert himself, but the patient Napoles slipped most of Ernie’s punches and started finding openings for his counter left again. Lopez fought gamely but simply lacked the power to gain the champion’s respect and a sharp hook put him on the defensive at the end of the round.

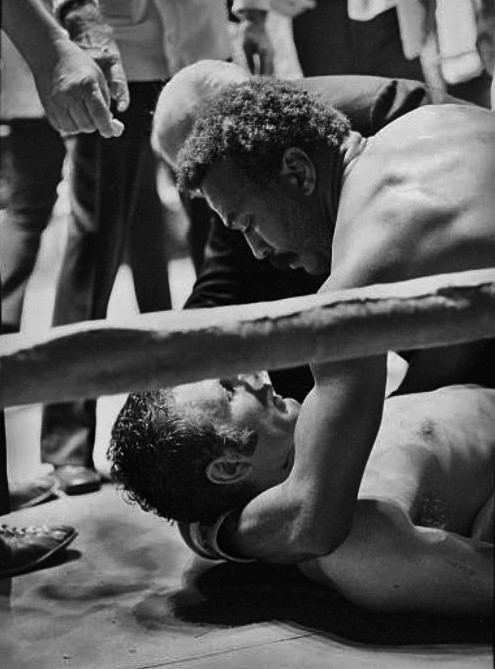

Napoles moved in for the kill in the seventh. Pressuring his opponent, he forced Lopez to trade, thus creating the opening he wanted for the left. The challenger tried to get home the big shot that would stop Napoles in his tracks, but instead a pair of crunching hooks hurt him badly. Backing his wounded quarry up, Napoles feinted another hook and then, in as vicious a knockout as you’ll ever see, countered Lopez’s right with a perfectly timed uppercut that put Lopez flat on his back. The challenger writhed in agony on the canvas as he was counted out and then stayed down for several minutes. At one point a concerned Napoles knelt near his fallen foe and cradled him saying, “Please wake up, please wake up.”

“I never saw power like that,” said the challenger’s veteran manager, Howie Steindler.

Lopez would not recover from the defeat. Following the bout he declared: “I’ll never fight that guy again . . . for any amount of money!” He lost to Muniz and Stracey before retiring, and not long after his marriage fell apart. Heartbroken, he abandoned his family and disappeared, living the life of a wanderer for over a decade before a private investigator found him in a homeless shelter in Texas. He died in 2009 from complications of dementia. He was 64.

“It was the losses to Napoles and the divorce that sent Ernie into a tailspin,” stated his brother, Danny Lopez, the former featherweight champion. “He was a hurt man.”

“He was a very good fighter,” said veteran L.A. boxing publicist Bill Caplan, “but Napoles was a great fighter.” — Robert Portis