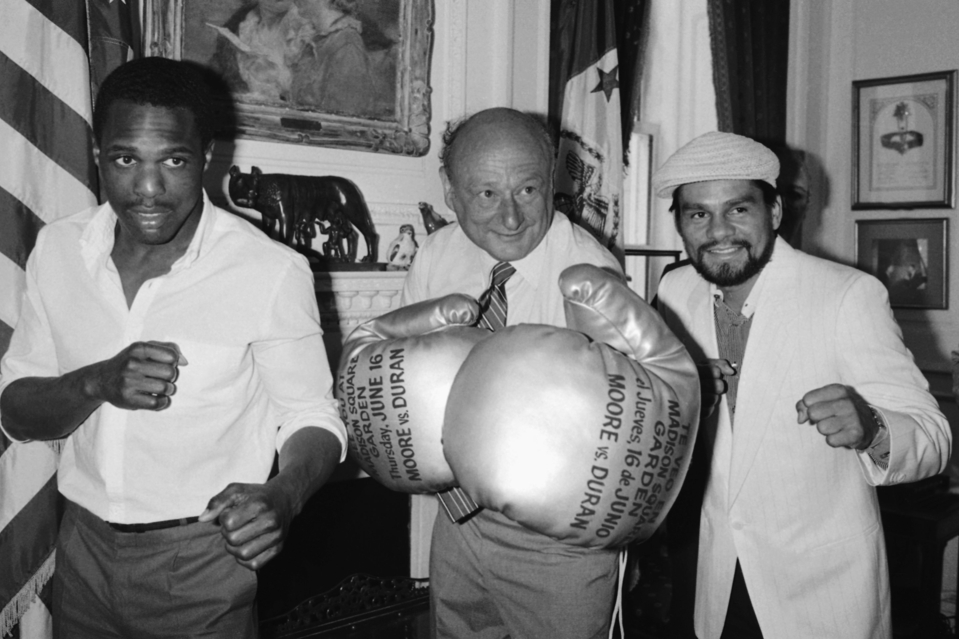

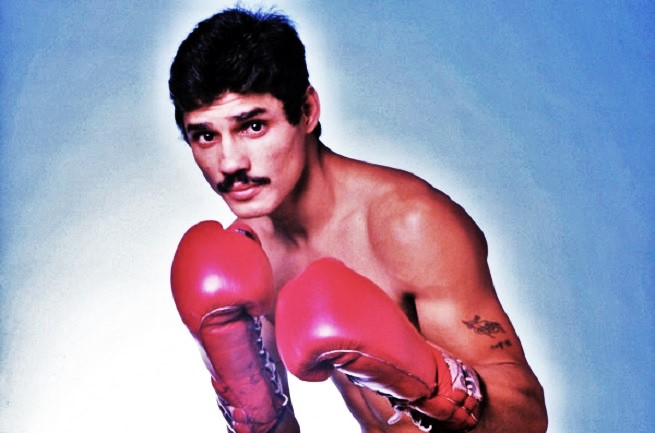

June 16, 1983: Duran vs Moore

In 1980, the career of Roberto Duran, a fighter widely regarded as a latter-day great, reached both its zenith and its nadir. Having abandoned a lightweight division he had dominated for more than seven years, and having proved himself one of the top contenders at welterweight with his one-sided win over Carlos Palomino, Duran journeyed to Montreal to challenge the American superstar, Sugar Ray Leonard. In one of the biggest fights of all time, the Panamanian surprised the experts who thought Leonard too young and too fast for the veteran former champ, as he won a close but unanimous decision after a thrilling fifteen round war. Already a hero to millions of Latin-Americans, Roberto was now unquestionably the best boxer in the world, and the ultimate flesh and blood symbol of Latin macho pride.

Then, in the rematch that took place less than six months later in New Orleans, Duran hit rock bottom after doing the unthinkable: he quit. It may be difficult now to appreciate how shocking this was at the time. Regrettably, quitting has become much more acceptable. But in 1980 it was something a serious competitor simply did not do, especially a champion as ferocious and proud as Duran. “No mas,” Duran said to the referee after abruptly raising his hands and turning his back in the eighth round of a fight quite different from the one that had taken place in Montreal.

It was a shocking moment, as shocking then as Mike Tyson biting Evander Holyfield’s ear sixteen years later, and the depth of Duran’s disgrace after his baffling capitulation was in the same league as Tyson’s. He was fined by the athletic commission, scorned by the media, and in his home nation of Panama his family found itself literally under siege from angry citizens who felt betrayed by their national hero. Amidst all the noise and condemnation, the disgraced former champ offered a single feeble excuse, insisting stomach cramps had forced him to give up both his title and his dignity.

Duran announced his retirement immediately following his surrender, but then changed his mind in a matter of days. He called for a third bout with Leonard, but everyone agreed this was out of the question. When Sugar Ray ventured into the super welterweight division, winning a second world title from Ayub Kalule, Duran followed. But after a pair of unimpressive decision wins over contenders Nino Gonzalez and Luigi Minchillo, he was soundly beaten by Wilfred Benitez, and then, in a huge upset, humiliated by the unknown Kirkland Laing.

Surely, this was the end. Duran looked positively inept against Laing, a relative novice who, just a year previous, would not have belonged in the same ring as the famous Manos de Piedra. Duran’s manager, his promoter, his long-time associates, all of them now abandoned “El Cholo,” and all urged him to retire for good before he got hurt, while in Panama he was now the object of ridicule and mockery. Humiliated and alone, Roberto Duran wondered if his detractors were right.

But his wife, Felicidad, knew this couldn’t be the end. “If you had any pride,” she told her husband, “you would demonstrate to Panama and the whole world that you are not finished.”

And so began the unlikely comeback. The first step was an inconsequential win over an unknown, Jimmy Batten. Duran looked old and slow in taking another decision victory as the experts shook their heads and sighed, lamenting the sad fate awaiting yet another shot fighter who just couldn’t walk away.

In fact, it would be Duran’s last decision win for some time. In the ensuing weeks, he began to seriously reapply himself to training and conditioning and slowly the spring returned to his legs and the snap to his punches. The next step was a bout with former world champion and heavy hitter Pipino Cuevas. Just three short years previous, a clash between these two Latin warriors would have been monumental, but both had since been humbled. The only question now was who had more left. The answer was Duran, who suddenly looked more spry than he had since Montreal, chasing Cuevas about the ring and knocking him down and out in the fourth round.

“Was Duran that good,” asked Davey Moore after watching the fight, “or was Cuevas that bad?” Moore, who held a world title strap in the 154 pound division, would soon find out.

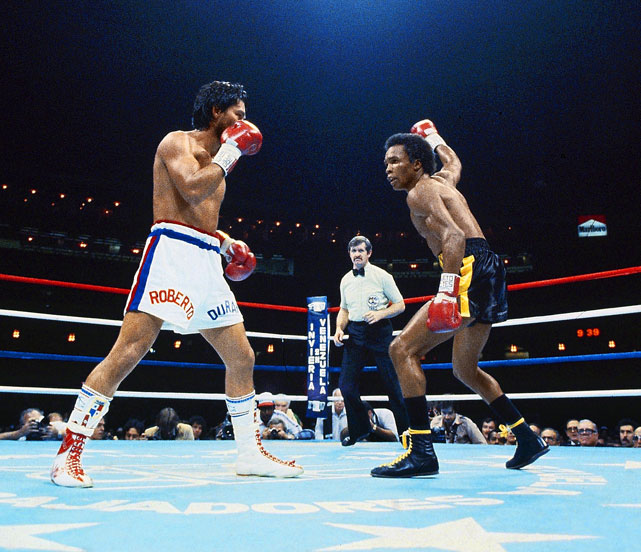

Duran vs Moore happened five months later, on Roberto’s birthday and in Madison Square Garden, the same site where Roberto had won his first world title from Ken Buchanan eleven years before. Younger, bigger and stronger, Moore was the betting favorite, but the fans who flocked to the Garden sensed it was finally Duran’s time for redemption. Moore, a New Yorker, found himself booed in his home city as the largely Latin crowd waved their homemade banners and shook the walls of the venerable arena with thunderous chants of “Doo-ran! Doo-ran!” It was a festive night, a huge Latin party, a homecoming for a once revered warrior who had been lost for too long.

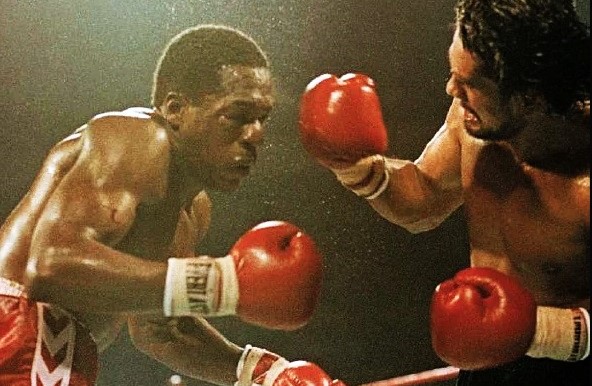

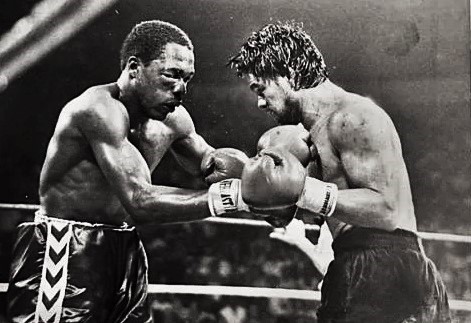

The fight itself was vintage Duran. Quicker, more aggressive, the Panamanian took charge from the opening round, dictating the terms and putting Moore on the defensive. Seldom had he looked better. His jab was crisp, his body punches so powerful they doubled Moore over. The smaller man, he used deft upper body movement and clever feints to get inside the champion’s longer reach and unleash powerful combinations.

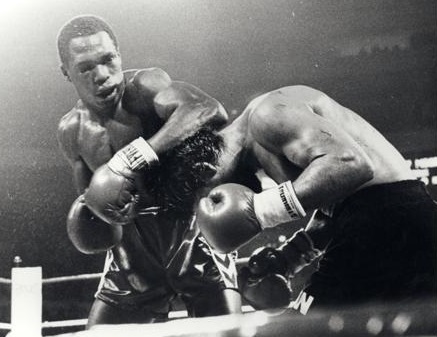

Near the end of the first round Duran’s thumb connected with Moore’s right eye and by the fourth it was swollen shut. Bleeding as well from the nose and lip, Moore fought back with courage but every time he threw a combination or forced Duran to give ground, Roberto answered back with fury, ripping heavy shots to the ribs, slashing Moore’s head and face with sharp jabs and right hands.

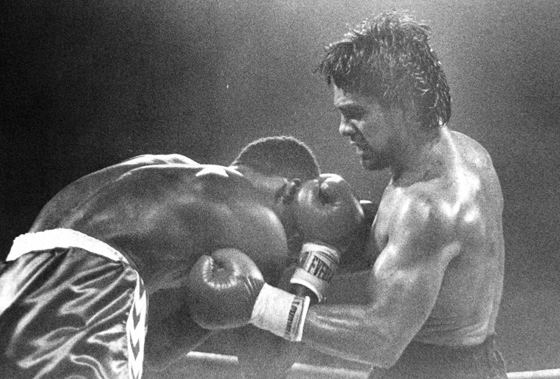

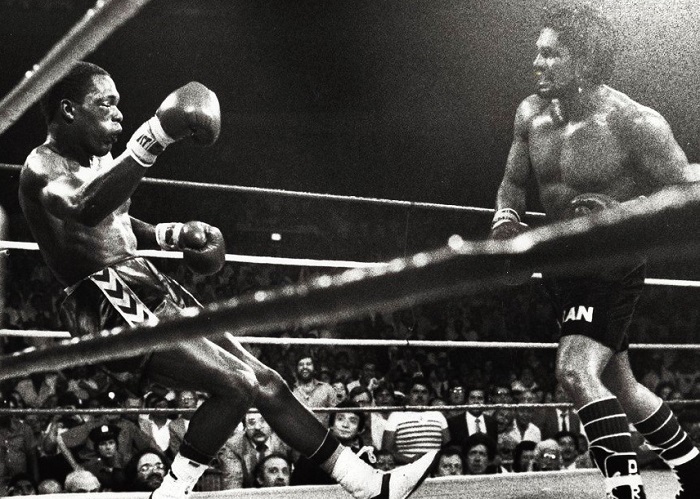

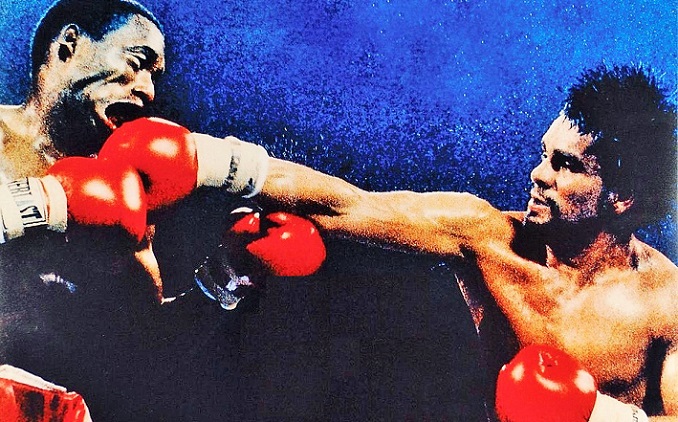

By the seventh, the outcome was obvious. Moore had little left and Duran was taking him apart. The sellout crowd rose to its feet and roared as the former champion, a contemptuous sneer on his face, landed one vicious combination after another, snapping Moore’s head from side to side and buckling his knees. Then, as if to reward the crowd’s enthusiasm, Roberto connected with a huge overhand right at round’s end that sent Moore crashing to the floor. Bravely the champion rose and staggered to his corner at the bell, the contest clearly decided, but instead of bringing the one-sided battering to an end, Moore’s people sent him out to absorb more punishment in round eight.

The referee, evidently a sadist, calmly watched as a merciless Duran pounded Moore from one side of the ring to the other, while various ringsiders shouted and pleaded for the fight to be stopped. Only after a white towel of surrender sailed into the ring from Moore’s corner, and several spectators threatened to storm through the ropes, did the referee finally signal a conclusion.

What followed was an extraordinary scene of collective absolution. The crowd erupted with joy, burst into a spontaneous rendition of “Happy Birthday,” and then continued to roar in an ovation lasting several minutes as the new champion, weeping, finally forgiven, stood on the ring apron and saluted them back. Roberto Duran had won his third divisional title, but much more importantly, he had restored his good name. The disgrace of ‘No mas’ was finally in the past. And now Marvelous Marvin Hagler waited in the wings.

— Michael Carbert

Would Duran have won without the thumb and low blows?

I guess we’ll never know.

Duran is not like Chavez who needed to ask the referees to step in and help him win.

It’s not a tickling match…

Watch the first round carefully, George. Duran threw a left jab and Moore tried to slip it. Moore put his eye right in the path of Duran’s thumb. Low blows? Duran is a body puncher; some blows will go low. I didn’t see any especially low. Did you? What round please? Duran was rough but he wouldn’t go dirty unless provoked.

When Roberto was hitting on all cylinders he was unbeatable as evidenced in this fight. I didn’t See any low blows only a boxing clinic by Roberto. Moore’s corner were incompetent letting their man take needless punishment. People judge Duran harshly after no mas, Roberto carried Panama on his back since 1972, the victory in Montreal went to his head and he got caught up in the party life of celebrity then paid dearly after 2 years of dissipation. Amazing comeback!!!