Plaster of Torrance (Part Two)

Plaster of Torrance: Unwrapping the Meaning of Antonio Margarito, Part Two. Excerpted from The Bittersweet Science.

There are times when boxing matches resemble more a bullfight than they do a sports contest, and that happens when only a deus ex machina will do in changing the outcome of such a match. Bullfights are all about the journey, and not the destination, as the inevitable outcome is that of a bull lying dead somewhere, even though there are many ways to arrive at that outcome. Likewise, after round seven, the ending of the fight between Miguel Cotto and Antonio Margarito, like its beginning, was already inked. The only mystery left was how bad a beating Margarito was going to put on Cotto. But it didn’t matter how certain the result of the fight became at that point, because you can’t take shortcuts in boxing. You can’t just jump to the end of a fight and skip everything that happens in between; to do that would be to miss everything that makes boxing boxing.

More than in any other sport, how and why one fighter wins and the other loses is of the utmost importance, and can have massive consequences for each one’s future. Of course, the in-between also has a significant impact on those who are watching the fights. How many who watched Cotto and Margarito fight struggled to repress a measure of horror at what they were watching? What does it say about us that we’re willing participants—and paying customers—in this sort of blood spectacle, in which someone as hurt and helpless as Cotto was for a large part of the contest had to endure so much bullying and physical punishment from a man who was obviously going to defeat him that night, all for reasons no more laudable than sport and business?

The question is not novel in any way, but that doesn’t take away from its sting. Fans of boxing have tried to deal with it for a long time, and all of us who enjoy the sport have learned that a corollary of our love for it is that we have to make peace with more than a few ugly truths. Each of us finds his own way of making this happen. For some the issue may have spiritual overtones; Norman Mailer called boxing “an old, primate religion of blood, a murderous and sensitive religion which mocks the effort of the understanding to approach it.”

If that seems like too much of a reach, maybe you’d like to consider Hemingway’s take on the morality of bullfighting and apply it to boxing: “I know only that what is moral is what you feel good after and what is immoral is what you feel bad after; judged by these moral standards, the bullfight is very moral to me because I feel very fine while it is going on and have a feeling of life and death and mortality and immortality, and after it is over I feel very sad but very fine.” If that also fails, I’m afraid we may have painted ourselves into a corner from which no rationalization can help us escape. Facing up to the facts, as Joyce Carol Oates does, is the only thing left to do: “all boxing fans know that boxing is sheerly madness, for all its occasional beauty; that knowledge is our common bond and sometimes our common shame.”

Shame, indeed, is a feeling most of those familiar with the rest of Margarito’s career remember vividly, especially those who cheered him on during his fight with Cotto.

***

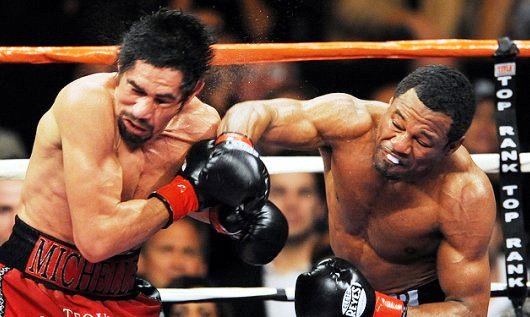

Six months after leaving Miguel Cotto a bloody mess in front of a two-thirds-full arena in Las Vegas, Antonio Margarito went to Los Angeles to fight Shane Mosley in front of a record-setting crowd at the Staples Center. The way Margarito defeated Cotto might have had a thing or two to do with his sudden boost in popularity. It’s safe to say that, in the aftermath of the Cotto win, Latino fans realized the Mexican’s style wasn’t a bad habit at all but was in fact the synthesis of Mexican boxing, something timeless and precious, to be cherished and celebrated, not something to get rid of. So the guy got hit a lot, big deal. As long as he dished it out worse than he got, he’d be fine. More importantly, it made for great drama, like watching a horse race with a slow starter that’s a great closer, that keeps you guessing as to whether he’ll turn it on in time to catch up and win. If the Cotto fight proved all this, the Mosley fight would corroborate it, and make him the best welterweight in the world at the same time. At least, that was what all those ticket buyers were thinking when they forked over their cash. As it turned out, they were wrong.

Two things happened to Margarito the night he faced Shane Mosley. The first was that his longtime trainer Javier Capetillo got caught trying to insert plaster of paris in his hand wraps before the fight. The second was that Mosley beat the crap out of him. The event turned out to be a far cry from the coronation implied by the four-to-one odds in favor of the Tijuanan. To see why, let’s look closer at both of those happenings, starting with the second.

The loss to Mosley has multiple possible explanations, and the real reason for it consists of a combination of them. Margarito’s go-to explanation is that he suffered greatly to make weight for the Mosley engagement, his outsized frame having finally outgrown the welterweight division. But it’s hard to imagine a scenario in which getting caught with an illegal substance on his wraps, whether or not he knew about it in advance, didn’t affect Margarito’s focus greatly during the fight. It also didn’t help his case at all that Mosley was in great shape that night—especially considering the fact he was thirty-six years old at the time—and had the perfect stylistic antidote to Margarito’s ruthless plodding. Mosley used his still considerable hand speed to get off first every time, landing strong, sharp punches in combinations before tying up and wrestling with Margarito. It’s worth noting that in his prime Mosley was a very strong puncher, fleet of foot and possessing enviable hand speed, but at his advanced age—with the diminished reflexes and physical attributes to match—standing up to a fearsome pressure fighter like Margarito would’ve represented a death wish.

On fight night, clinching after attacking proved as brilliant a tactic for Mosley as it had in the past for many other cagey veterans seeking to frustrate younger, more powerful opponents. It also represented a creative variant of Miguel Cotto’s game plan. Both Cotto and Mosley acknowledged, if reluctantly, that a toe-to-toe battle favored Margarito and so they both sought to outbox him. However, the two welterweights approached the same problem in different ways. Cotto attempted to outwork the Mexican and then get out of the line of fire—a game plan fully backed by Cotto’s confidence in his own abilities and in line with the boxing aesthetics honored by the most successful Puerto Rican boxers, among them Wilfred Benitez and Hector Camacho. Alternatively, Mosley outworked Margarito and then smothered his attack with clinches. Cotto’s approach yielded a furious debate with Margarito on the character of warfare, ultimately decided in favor of all-out battle over scattered, focused skirmishes; Mosley, for his part, turned his fight with Margarito into a droning monologue on the importance of efficiency, disallowing the Tijuanan the very capacity to rebut him. Naazim Richardson, a trainer known for helping former middleweight champion Bernard Hopkins extend his career to preternatural lengths by employing exactly that sort of trick, was the man behind Mosley’s plan. Round after round, Mosley went to work, never deviating from his well-laid agenda, capping off his performance with a highlight-reel knockout that ultimately laid waste to any hopes of a comeback rally that Margarito’s fans might still have held after nine terribly one-sided rounds.

The outcome shocked a large majority of observers, most of whom had no idea of what had happened in Margarito’s dressing room before the fight. While the broadcast team mentioned the incident on air right before the start of the contest, it could’ve easily been missed by those watching. Those present in the arena had no way at all of learning about the plaster found in the wraps of the fighter they had paid good money to cheer. But everyone caught up to it soon enough, through websites and newspapers, turning the humiliation into a delayed double whammy: Margarito lost the fight that night and then had his reputation ripped to shreds the next day.

Shane Mosley must have experienced a mixed bag of emotions after the fight as well, as his own career had already gone through an arc similar to Margarito’s. In 2003, Mosley, having already once defeated Oscar De La Hoya, scored a big win in their rematch in Vegas. That same year, as part of the federal investigation of the Bay Area Laboratory Co-operative (BALCO), the famed purveyor of anabolic steroids to professional athletes, Mosley admitted that in preparing for the second fight against De La Hoya he took steroids and other performance enhancers—some of them illegal but undetectable, others not even tested for at the time. Mosley, just like Margarito following the plaster incident, claimed ignorance of his wrongdoing, regretting only the blind trust he placed in his strength and conditioning coach, Darryl Hudson, who had introduced him to BALCO and its products. Just as Margarito’s biggest win—his entire career, actually—was tarnished by the discovery of plaster in his wraps before the Mosley fight, Mosley saw his own reputation and the validity of his second victory over De La Hoya undermined by the BALCO revelations. For both the man whose fists were compared to rocks and the man whose speed was deemed borderline unnatural, admiring metaphors turned into scandalously literal truths.

The plaster incident raised questions regarding Margarito’s career in general and about the fearsome display against Cotto in particular, as that was the performance that raised his profile and made his reputation as a stone killer. How could it be any other way? Margarito became the highest-ranked welterweight in the world based on the damage he caused his opponents with his fists and nothing else. He never showed the faintest notion of defense; his footwork was awkward at best; and even his punching technique was subpar. Margarito practiced the most physically taxing, most dangerous brand of fighting a boxer could practice, and everything the Mexican accomplished could be traced to three attributes alone: his apparently indestructible chin, his extraordinary punching output, and his fists’ ability to hurt people.

It remains up for debate—and it’s probably a moot point now—how much of Mosley’s success the night he faced Margarito was due to Richardson’s fight plan and how much of it was due to his opponent being distracted by his imperiled reputation. Whether Margarito knew all along about the plaster in his wraps or only found out about it at the same time the officers of the California State Athletic Commission (CSAC) did, the discovery of the plaster had to affect his performance against Mosley. Not much will dent a fighter’s self-confidence as badly as knowing his trainer feels he has to cheat—and if his trainer had done it without telling him, Margo had to realize that perhaps he had unwittingly been made to cheat on past occasions. Maybe he wasn’t the puncher he thought he was. Regardless of how much he knew before the discovery, Margarito’s mind would’ve been juggling the torpedoing of his reputation and the legal ramifications of what had just happened, perhaps even the prospect of doing jail time, at the very moment an extremely focused Mosley aimed and fired right cross after right cross squarely at his chin and then wrapped him up in a clinch before he could respond.

The revelation that a trainer inserted plaster of paris in his fighter’s wraps, no matter the pugilist’s fighting style, would never go unnoticed or dismissed as irrelevant. But the fact that Margarito was the fighter whose fists almost tore Sebastian Lujan’s ear right off his head, the one whose fists turned Cotto’s face into a morbid museum piece and left him a helpless victim in Las Vegas, made it all seem much, much worse. If the incident was a willful attempt at cheating, it made Margarito a double cheater, as inserting hardened plaster in his wraps would mean he not only competed on a grossly uneven playing field, but also that he tricked everyone into thinking he was a lot more fearsome than he really was. After Margarito left the ring of the Staples Center in disgrace, and after the legal proceedings were over and the trial by media had taken place, it was Javier Capetillo who took the fall for the plaster debacle. He declared it was all a mistake, that some other fighter he trained possibly threw the plastered wraps in his bag, and then he, Capetillo, mistakenly grabbed those altered wraps and inadvertently used them to wrap both of Margarito’s fists before Mosley’s trainer and the CSAC officers identified them and forced him to remove them. As far as Capetillo was concerned, it was all an honest and terrible mistake. Margarito, for his part, maintained he had no knowledge of anything illegal being hidden in his hand wraps, for the Mosley fight or for any other of his fights. He also proclaimed that he trusted his trainer fully, so much so that he didn’t even look at what Javier wrapped around his knuckles before his fights. Those inclined to believe Margarito and Capetillo can surely find comfort in declarations obtained by the media from celebrity trainers—Freddie Roach, Emanuel Steward, Don Turner—shortly after the plaster incident stating they could, plausibly and hypothetically, get away with hiding an illegal substance between the wraps of their fighters without them becoming aware of it. Even Naazim Richardson, who first raised the issue of Margarito’s wraps in the Mexican’s dressing room that night in Los Angeles, admits that a trainer could get away with it if he wanted to.

Whether it was just a mistake or bald-faced cheating, the legal consequences for Margarito and Capetillo were concrete, although too mild in the eyes of many. Javier Capetillo—who had been in corners and trained fighters in the United States for years—was no longer allowed to work any bout that took place on American soil. As for Margarito, his fighting license was revoked for a year. If he wanted to box in the United States after the ban was lifted, he would have to apply for a new license.

Margarito cut off all ties—at least publicly—with Capetillo, the man who had trained him for over ten years and to this day considers himself a father figure in Margarito’s life. Anything else to be said about the case is, unfortunately, pure speculation. There’s no way to prove whether what Capetillo was caught trying to do was intentional or not, just as there’s no way to prove whether Margarito knew about what Capetillo did—mistakenly or not—the night of the Mosley fight. It’s even more difficult to prove whether Margarito had plaster hidden between his hand wraps for any of his previous fights. In several interviews he’s given since, Capetillo has always denied any intention of cheating for the Mosley fight, for the Cotto fight, or for any other Margarito fight he worked. He has also always maintained his stance that Margarito should be exonerated of any blame, that what happened in Los Angeles was entirely his own fault.

Capetillo has never deviated from that story. We can’t tell, of course, whether he’s just sticking to the most plausible cover or genuinely contrite about an honest-to-God mistake. But if Capetillo inserting plaster into Margarito’s wraps was done on purpose, and if Margarito had knowledge of this, it’s at the very least interesting that Capetillo would keep defending Margarito and keep averring that he thinks of the fighter as his son even after Margarito and the rest of his team not only allowed Capetillo to become the sole scapegoat—something that had a direct bearing on his ability to make a living—but effectively cut him off completely, severing all financial, professional, and emotional bonds that existed between them both. Under these circumstances, Capetillo would have little incentive to keep defending Margarito, and yet he continuously does so every time the issue comes up. Of course, a sense of honor can work in mysterious ways, and Capetillo could also be an intentional cheater who feels guilty enough to believe he has to take the fall for his misdeeds.

***

Every member of the madly dysfunctional family that is boxing—every fan, every member of the media, every blogger, every suit, everyone with skin in the game and many without—has his own opinion about Margarito’s plaster debacle. They all have carefully and selectively built their own case for or against Margarito’s innocence, collecting tidbits of information here and there, focusing on some apparently insignificant details while dismissing others, all of this based on individual preferences and biases. But the ultimate truth about the biggest questions regarding Antonio Margarito—Was there plaster in his hand wraps for any of his fights? Did Capetillo ever cheat for his fighter, and did Margarito know about it?—will in all probability never be known, and is in all likelihood irrelevant at this point, at least from the point of view of anyone who’s interested in The Truth.

When Antonio Margarito says he was born in Mexico even if a hospital in Torrance begs to differ, maybe he’s just seeking immunity from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s dictum that there are no second acts in American lives. Just as the reputation of his fighting style made a major comeback following his overpowering of Cotto, Margarito himself, with no shortage of help from promoters, athletic commission officers, and network executives, staged a comeback that rendered irrelevant, even laughable, any attempt of finding The Truth regarding what happened that night in Los Angeles.

Throughout his year as a boxing pariah, Margarito never lost the desire to box again, and to do so on the grandest stages the sport could offer. Once his year was up, his promoter, Bob Arum, latched on to that desire, and on to Margarito’s notoriety, to stage two huge bouts. The first was a money-grabber in Dallas against Arum’s most prized asset, Manny Pacquiao. The marketing buildup promoting the fight presented a remarkably different Margarito from the one who was forced to walk away from the spotlight following the Mosley affair. Gone was his clean-cut image. Fans were instead served images of his heavily tattooed torso, a devilish goatee, and a mullet that made it look as if Margarito had indeed spent a year in jail. His demeanor had changed too: in interviews taped to promote his bout with Pacquiao he alternated between playfulness and remorse, also apologetically addressing the issues of the events in Los Angeles and his parting ways with Capetillo. If Margarito was to be rehabilitated as a good guy who had gotten mixed up in an unfortunate wrongdoing, he would have to offer at least a semblance of regret to HBO’s cameras.

But that wouldn’t be necessary if he was going to wear the black hat. After Margarito lost a unanimous decision by wide margins on all cards to Pacquiao, his second big comeback fight was a rematch against none other than Miguel Cotto, in New York City. The promotion for it included a staged face-off between the two fighters, with Cotto brandishing a tablet showing a picture of Margarito celebrating his victory over him, being carried around on someone’s shoulders in the ring in Las Vegas. Then Cotto zoomed in on the picture, confronting Margarito with a close up of his ungloved but still wrapped right fist, which showed a peculiar tear that would be very difficult to explain without the presence of some foreign, hardened material hidden somewhere in the wraps. Margarito dismissed it nonchalantly, pretending not to understand Cotto’s allegations (even though both were speaking Spanish) and ending the segment by stating, “I’ll beat you up again!” It made for riveting television, something straight out of the WWE, and showed in its final form Margarito’s newly adopted persona as ring villain. The mullet, the tattoos, the facial hair, the insolent attitude—they all amounted to a new character, one far removed from the humble, soft-spoken Margarito who beat Cotto and lost to Mosley. Margarito had finally realized that neither modesty nor self-effacement were valuable in the business of boxing, so he remodeled himself as a justifiably remorseless douche: if he had done nothing wrong—as he always maintained—then there was nothing to apologize about. The rest of his felonious persona was only to help sell tickets.

And sell it did. Over forty thousand tickets were bought for the Pacquiao fight in Dallas’s enormous Cowboys Stadium. The rematch with Cotto packed New York’s Madison Square Garden. Margarito earned more for the second fight with Cotto—over $2.5 million—than he did in what was supposed to be his coronation bout against Mosley. Not bad for a guy whose reputation had been in ruins only a short time before. Everyone seemed to come out a winner from Margarito’s comeback. The Tijuanan squeezed a couple of juicy paychecks from his name and his newly crafted image while giving Miguel Cotto a chance at lucrative revenge, fans someone to root against, and the promoters and networks a chance to cash in. Moreover, Margarito played to perfection the role that had been handed him: not only did his malevolent reincarnation touch fans and the media in the right spots, this evil Margo also lost both big fights. And not only did he lose, he lost big. Pacquiao busted up his right eye so badly, breaking the orbital bone, that all Cotto had to do was throw some water at it for Margarito’s eye to swell shut. Cotto went instead with a never-ending string of left hooks, which also got the job done.

Looking at all the money produced by Margarito’s comeback for HBO and for Bob Arum’s Top Rank, in retrospect it looks silly to suggest it never should have taken place. But with such an obvious financial imperative at play, it became a safe bet that there was little call for further investigation into Margarito’s and Capetillo’s behavior in Margo’s previous fights. Nobody who mattered in the fight world needed to know The Truth about what happened to Lujan, Cintron, and Cotto at the hands of Margarito, not when promoters and networks could forge their own version of the truth, package it, and sell it for mass consumption. Still, if nothing else, two hard-hitting facts emerged from the Tijuana Tornado’s comeback: 1) Antonio Margarito lost the two high-profile fights he had after Javier Capetillo was caught trying to insert plaster in his wraps; 2) Margarito lost the two high-profile fights he had after cutting his ties with Capetillo. Is there any way to make sense of the relationship between them?

Seen from a distance professional boxing is a deceptively simple spectacle: two men beating on each other until cunning, physical prowess, or a combination thereof produces a winner. But complexity increases as we zoom in, as the business side—nothing more than a manifestation of human nature—interferes in all sorts of ways with what most fans would rather believe is a purely athletic competition. Many who watch boxing never move past their romantic notion of the sport, constantly framing what they see in terms of platonic concepts such as courage, valor, honor, and pride. Yet those same notions are hammered into irrelevance by forces significantly more pressing to the fighters and the suits promoting and managing them, namely, money, power, and influence. Narratives we attach to fights and fighters differ from one viewer to the next depending on how much they care to learn about what they’re watching, and—as both Cotto-Margarito and Margarito-Mosley abundantly demonstrated—the narratives can also change over time contingent on information that surfaces after the fact. The sport offers no truths, but only informed beliefs to subscribe to; each being valid to some extent, but each also flawed in its own ways. The Truth is there’s no purity in boxing; there are no absolutes to rely on. Enlightenment is to be found in the ring only on occasion and fleetingly; outside it, there’s only the insouciance of a Socratic paradox: not all we see is real, and we’ll never see it all.

Joyce Carol Oates is right when she says boxing can offer us beauty in the ring, and the first fight between Cotto and Margarito—at least when we saw it live—certainly proved this. But if Margarito’s comeback proved anything else, it’s that she’s wrong in calling boxing “sheerly madness,” just as Norman Mailer was wrong about calling it a religion, and just as Ernest Hemingway would’ve been wrong to declare it moral because of how fine and alive it can make us feel. If boxing is anything more than a sport, it is business: rational in its pursuit of profit, passionless in dealing with its own consequences, and amoral in pursuing its goals. Margarito’s becoming a boxer at age 15 was entirely a business decision; his comeback in spite of all the disturbing circumstances and open questions surrounding it, questions that also threatened to undermine the validity of what those who love boxing think they see when two boxers go to war in the ring, was just business as usual. — Rafael Garcia

Great article, very well written.

The only point I disagree with is the idea “Capetillo would have little incentive to keep defending Margarito”… Capetillo is still maintaining that it’s an accident & thus Margarito can’t have known about it. If Capetillo were at this point to say it wasn’t a mistake & Margarito knew about it, then at best Capetillo could be sued by Cotto (or even sued by Margarito for defamation) and at worst he could go to jail.

Whatever the truth, there is plenty of incentive for Capetillo to stick to what he has said all along.

Cotto knows damn well he lost to Margarito fair and square in their first fight. Keith Kizer, who headed the NSAC when this bout took place, is on record saying that Margarito’s hand wraps and gloves weren’t doctored against Miguel Cotto.

This is the report from “badlefthook“ :

“Diaz(Margarito’s co-manager) believes representatives of the Nevada State Athletic Commission took custody of Margarito’s hand wraps after the Cotto fight. But Keith Kizer, executive officer of that commission, said Margarito never turned over his hand wraps to Nevada authorities, and wasn’t asked to.”