The Story Of The Cincinnati Cobra

Like anyone who identifies as something of a boxing diehard, I’m familiar with the name Ezzard Charles. However, if pressed I could not tell you much more than this: that Charles famously beat Joe Louis during the latter’s ill-advised comeback and that he is touted by many knowledgeable scholars of the game as, pound-for-pound, one of the greatest pugilists in boxing history.

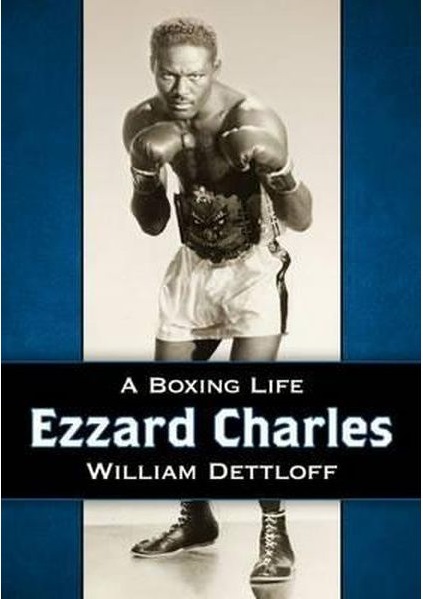

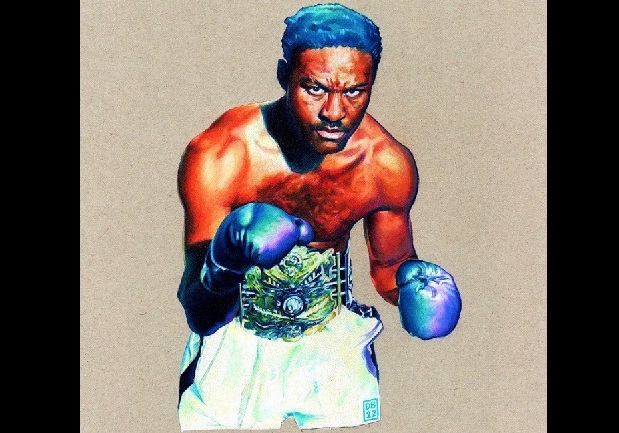

Or, I couldn’t have told you much more prior to reading William Dettloff’s excellent biography of the man, Ezzard Charles: A Boxing Life, the first publication of its kind, a shocking fact given Charles’ standing. Dettloff, a former senior writer at The Ring and now editor-in-chief of the e-magazine Ringside Seat, writes with clarity and authority about the great Cincinnati Cobra, beginning with his early years in Lawrenceville, Georgia.

It is to Dettloff’s credit that Charles’ upbringing is framed in the proper historical context: “The year Charles was born, there were sixty-three documented lynchings of blacks in the United States. Over the next ten years, forty-one African Americans were lynched right there in Georgia.”

Into this brutal milieu comes Ezzard, named – in lieu of payment – after the town doctor who delivered him. A hardscrabble life awaits: his father William departs when he is just five, not to be seen again for two decades, and after this the future heavyweight king is raised mostly by his wizened grand- and great-grandmothers in Cincinnati’s tough West End, in “a rundown, three-room frame house supported by bricks at the corners.”

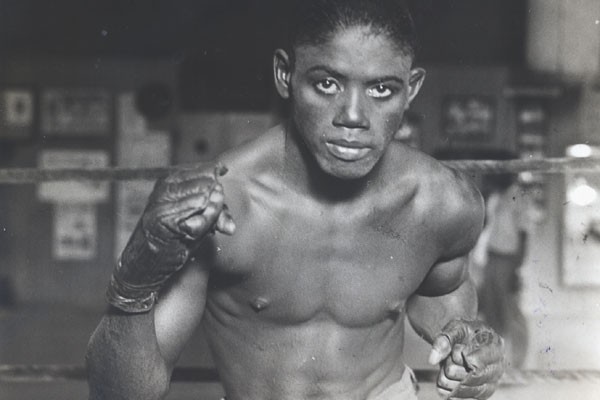

Given the dearth of material available on Charles, save for sepia-toned back issues of fight magazines and grainy contest footage, these early passages of the biography offer a wonderful insight into his formative years and what made him tick. We learn that Ezzard Charles was a timid kid, the prey of school bullies, God-fearing, yet a locally celebrated scrapper, participating in rudimentary backyard boxing matches from the age of eight.

The research which has clearly gone into this work is enjoyably evident, as when Dettloff informs us that young Ezzard’s zen for the sporting life was ignited after he encountered the great Kid Chocolate, in town to face Cleveland-based journeyman Johnny Farr:

“The week before the fight the promoter had one of his guys drive Chocolate through the West End to help build the gate. The car was huge and had the top down and Chocolate sat up high, waving to the neighbourhood kids. They turned down the block Charles and his family lived on, and stopped outside a candy store.

“The neighbourhood kids flocked to the car and Chocolate, known not only for his ring prowess but for an immense and elegant wardrobe, shone in an expensive, impeccably tailored suit despite the summer heat… And Ezzard Mack Charles, who was about as poor as any of the kids on the West End, [who] ran from fights in the street, looked like he was half starving to death, and never spoke unless he was spoken to, thought: ‘I’m gonna be a fighter and have clothes like that.'”

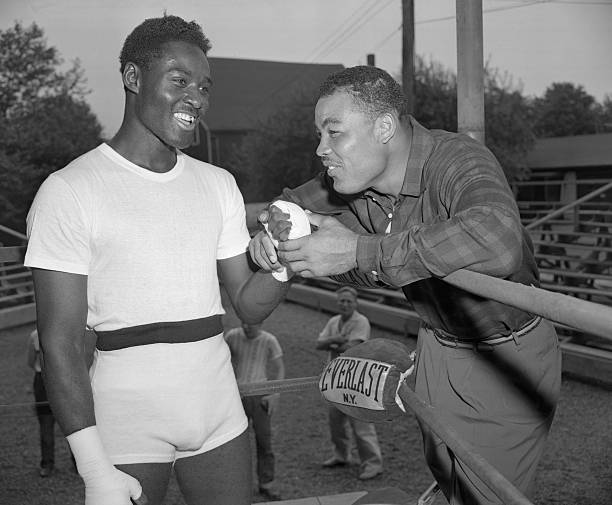

We learn about Ezzard’s idolizing of Joe Louis, and his amateur success in Ohio under the tutelage of “diminutive Welshman and World War I veteran” Bert Williams, who nurtures his “aggressive, fast-handed, fearless style,” and plenty more besides. Dettloff gives us snapshots of the boxing landscape in the ‘30s, ‘40s and ‘50s, an era when “crooks and gamblers had their fingers in the game… Gamblers, hustlers, drunks, whores, killers; they all felt at home in the fight business because they were among their own and because nobody was there to stop them.”

The book is an engaging portrait of a marvellous pugilist who wreaked havoc in the ring but beyond the ropes remained “humble, honourable, hard-working and all the other things you wanted your kid to be when you sent him off into the world.” In other words, a man apart from mobbed-up figures like Blinky Palermo and Frankie Carbo, prominent fixtures in the Golden, but shady, Age.

Fight footage on Charles is scarcer than we’d like, but Dettloff capably charts his rise through the ranks from the moment he turns pro in 1940, earning a modest purse of $5, and helps us visualise the ferocious action under the lights. A year after his debut, still just a teenager, Charles fights Ken Overlin, a veteran ranked by The Ring as the world’s second best middleweight. Dettloff describes it as a calculated risk: “Overlin had so much more experience than Charles that he was expected to win. If it turned out that way, and even if he gave Charles a thorough going-over, it wouldn’t ruin him because Overlin couldn’t break an egg. And if Charles managed to pull out a win? Well, that would be a hell of a notch in his belt…”

But it was Overlin who got the notch: “Everything that Charles had going for him – his youth, his strength, his speed, his hunger – wasn’t enough to overcome what Overlin had, which was experience … Overlin took his time, letting Charles make all the mistakes young fighters make, letting him burn out so that by the end he was wobbling all over the ring. And right there in Charles’ hometown, the judges gave Overlin the win, just as they should have.”

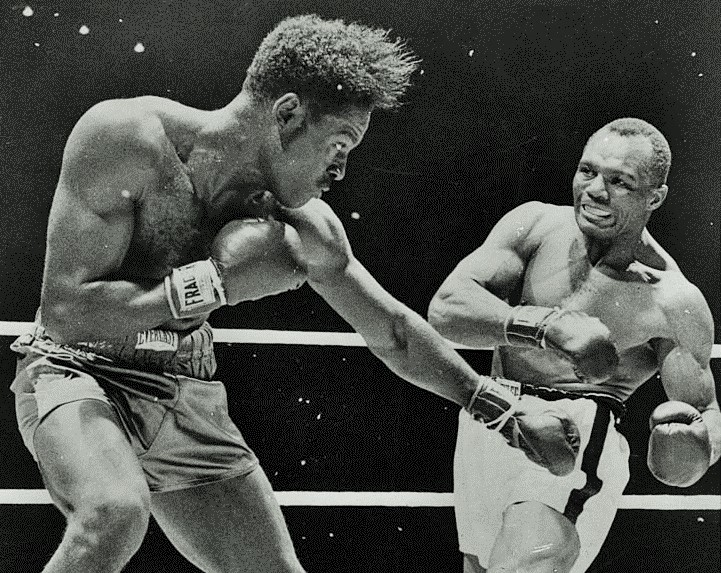

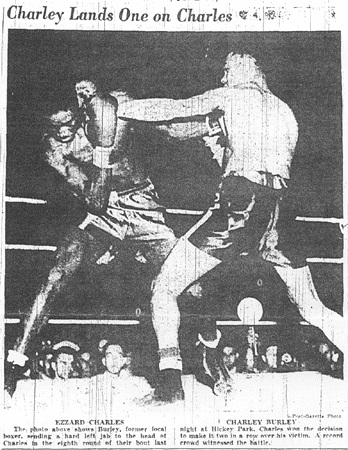

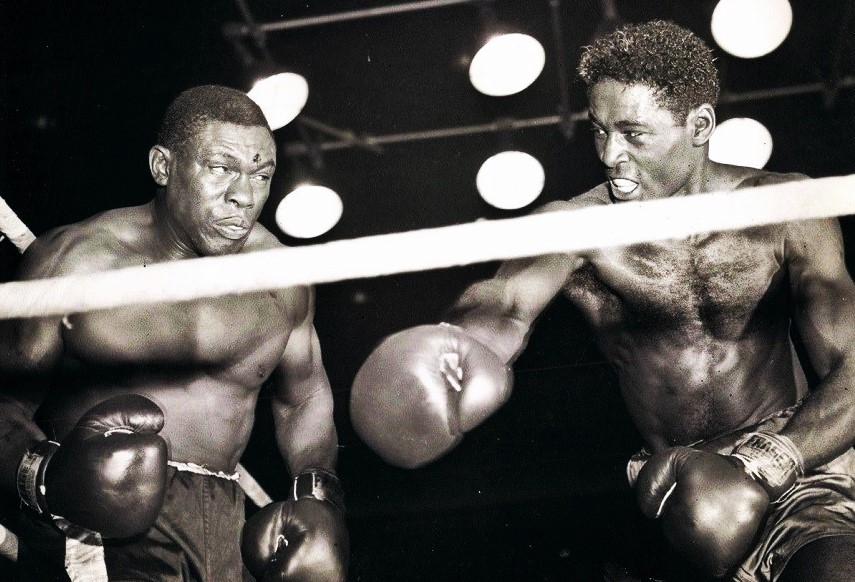

As we know, this early setback does little to deter the gifted Ezzard Charles, and his evolution as a boxer is well documented as he carves out a reputation as one of the best young prospects in America. In the following years he fights and beats a succession of formidable middleweights and light heavyweights, champions and ex-titlists, including Teddy Yarosz, Anton Cristofiridis, Charley Burley, Booker Beckwith, Mose Brown and Joey Maxim.

He also loses, to “slick and crafty” Kid Tunero, and to Jimmy Bivins and Lloyd Marshall, the latter two defeats later avenged. Dettloff makes sure we’re aware that in many cases Charles had to overcome significant size disadvantages to have his hand raised. Thanks to the author’s unfailing commitment to detail, the reader is left in no doubt about just how special this kid was in his prime.

The business entanglements are also covered: Charles severs ties with Williams and is guided largely by firebrand Pittsburgh promoter Jake Mintz, as well as a management collective comprising an accountant, a restaurant proprietor, and Max Elkus, owner of a clothing store Charles had worked in after school. In fact, “Charles felt so indebted to the Elkus family that even after he was making a lot of noise a pro, he’d go back to the store when they were busy over the holidays and get behind the counter.”

Following successive defeats to Bivins and Marshall in early ’43, Uncle Sam comes calling and Dettloff gives us the details regarding Ezzard’s enlistment and basic training in Texas, and how he “refuses to use his meager celebrity as a top-rated prizefighter to get special treatment while in the military.”

All the same, his buddies push him into sparring with the great Joe Louis, who is touring bases in the area and conducting boxing exhibitions. Perhaps it is this experience which convinces Ezzard to resume his boxing career after service concludes, service which includes a stint with a truck battalion in Oran, North Africa, and sees Charles promoted to corporal before being busted back to private. Charles also winds up boxing for the Army in inter-allied tournaments throughout Europe, enjoying predictable success.

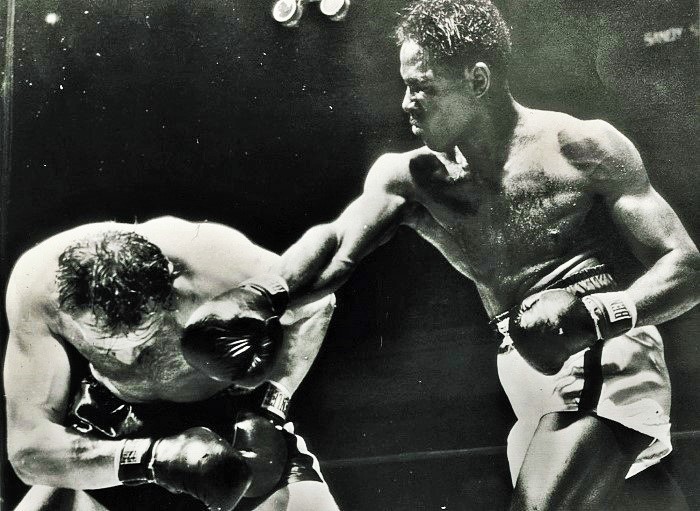

Discharged in January 1946, the career of “The Cincinnati Cobra” then motors on in high gear and reading about his bouts with the legendary Archie Moore in particular is a great pleasure. “Everything that Charles had been before the Bivins fight he was again: fast, powerful, hungry and indefatigable … Moore, as good as he was, and as cagey and strong as he was, never stood a chance.”

Between 1943 and 1951, a truly stacked era, Charles loses just once, an unpopular split decision to veteran heavyweight and lethal puncher Elmer Ray, a defeat which he avenges by knockout a year later. Incidentally, these opponents – Ray, Bivins, Burley et al – are not glossed over but given a proper backstory, Dettloff making them come alive on the page and increasing our appreciation for Charles’ achievement in vanquishing them.

Of Elmer Ray, the author writes: “He was born into a family of six girls and three boys to a potato-and-cabbage farmer near Hastings, Florida. The family didn’t own a Bible in which to record the birth dates of each of their kids, which was the custom in those parts, so they kept a record by making notches on the trunk of an oak tree that sat on their property. Some time after their ninth child was born, a fire burned down part of the tree and seared off the notches. After that, everyone’s age was more or less a guess.”

The political finagling to arrange title shots in those days is similarly well sketched, and if you think Don King was reptilian, reading the sections which cover the immediate aftermath of Joe Louis’ championship reign is truly eye-opening. I learned much about ‘Uncle Mike’ Jacobs, Louis’ chief powerbroker, as well as figures from the National Boxing Association and International Boxing Commission, organisations which ruled the boxing roost at that time.

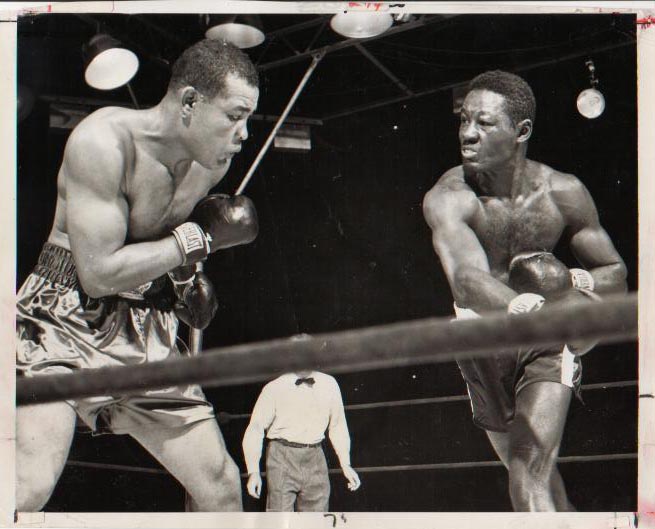

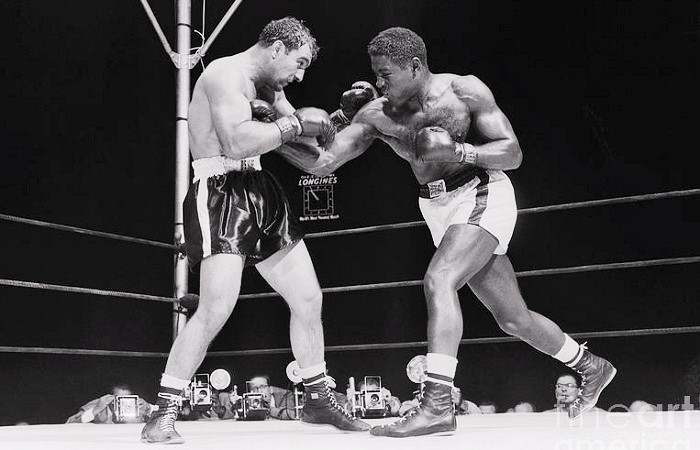

But Ezzard Charles is so damn good that, despite being avoided to an almost comical degree by light heavyweight champ Gus Lesnevich, he winds up making waves as a heavyweight, capturing the world title left vacant after Joe Louis retired by taking a 15 round decision over Jersey Joe Walcott in 1949, repaying Lesnevich in his maiden defence, and then going on to defeat his old idol, Louis. This streak of success is all the more surprising in light of Charles’ tragic win over 20-year-old Sam Baroudi in 1948, following which Baroudi died after suffering a harrowing beating at Ezzard’s hands.

Although heavyweight was mostly a happy hunting ground for the preternaturally gifted Charles, he was an unpopular figure among fans who remained loyal to the great Joe Louis. Dettloff captures the tragedy of an audience booing and catcalling one of the sport’s greatest practitioners as he slips through the ropes, his perceived inability, or unwillingness, to register conclusive knockouts a constant mark against his name.

“Fight crowds,” writes Dettloff, “liked blood and guts and gory displays of violence.” Louis had given them crushing knockouts and awesome displays of raw power; Charles was a pugilist of a different stripe.

It all adds up to a fascinating boxing biography, one of the most exhaustively researched I’ve come across. And one which illuminates the essence of the sport while sympathetically documenting the life of one of its cleverest exports, with searing passages describing the lure of the Fancy.

“Chances were they’d wind up broke, mumbly and punchy like all the rest, but what of it? What else were these slum kids going to do? Work themselves to death in a factory? Shine shoes on a box in Times Square? At least the fight game would get their filthy immigrant blood flowing for a while.

“If they were any good they’d hear a crowd cheer for them, they’d get a few dames that were hotter and looser than what they’d get otherwise, and maybe they’d get their name in the paper once or twice. That was better than most of the bums in the neighbourhood. Plus they’d get to know the singular joy of cracking a man on the jaw with a perfect left hook.”

Ezzard Charles knew that joy well, and thanks to this satisfying biography we now know a good deal more about the man and the all-time great fighter that he was. Any devotee of “The Sweet Science” should add this volume to their Required Reading list, without delay. — Ronnie McCluskey

Great review, thanks.

I have a bracelet given to a boy, last name Charles when he was born in Cincinnati. My mother delivered the boy perhaps in the 1950’s or 1960’s. I would like him to have it. Please let me know how to contact someone regarding this. Thank you.

Ezzard Charles is my great-uncle his sister name was Audrey Katherine Charles .