Scribe Of “The Fancy”

Great stories always involve great characters, so it makes sense that so many fiction writers have taken boxers as their subjects. Few sports make such drastic demands on the individual as boxing, which is why great fights have such strong narratives. Boxing is ready-made for short stories and novels.

But most scribes who have written about the fight game have been outsiders, fans and pundits, not boxers themselves. Jack London, who wrote the classic pugilistic story “A Piece Of Steak,” was an amateur fighter and as a journalist covered some of the biggest bouts of his day, including the famous Jack Johnson vs James J. Jeffries bout in 1910, but he made his fortune as a wordsmith. Joyce Carol Oates, perhaps the most unexpected and eloquent fight fanatic in contemporary letters, never claims to be more than a keen observer of The Sweet Science. Ernest Hemingway and Norman Mailer did their share of gym workouts and sparring, but could not claim to actually be part of the boxing world.

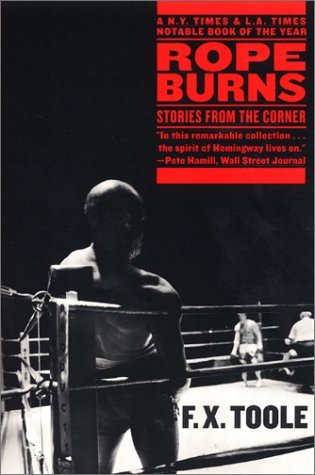

But there is an exception, a renowned writer who was in fact active in the sport: F. X. Toole. Most people are familiar with Toole through Clint Eastwood’s film Million Dollar Baby, which is based on two stories from Toole’s debut short story collection, Rope Burns. While Toole may not have the fame of the writers mentioned above, his fiction is required reading for serious fight fans, not only because of its literary quality but because of the insider information he offers which few other writers can access.

But there is an exception, a renowned writer who was in fact active in the sport: F. X. Toole. Most people are familiar with Toole through Clint Eastwood’s film Million Dollar Baby, which is based on two stories from Toole’s debut short story collection, Rope Burns. While Toole may not have the fame of the writers mentioned above, his fiction is required reading for serious fight fans, not only because of its literary quality but because of the insider information he offers which few other writers can access.

F. X. Toole, the pen name of Jerry Boyd, was late to the fight game. He didn’t start training in a boxing gym until he was 46 years old, and while he never fought professionally, he went on to make a living for himself as a trainer and a cut man. Previously he’d worked a myriad of jobs, including a turn as a matador. But like so many others, after he discovered boxing, that became his life, his identity.

But unlike so many others, he also wrote. For decades, while he worked corners and trained fighters, he never told his friends in boxing about his writing because he failed to get any of it published. But when Toole was 69 his first story appeared, which led to his first book-length collection and eventually a novel which was published after his death. He is the boxing insider who also became a literary hit.

Toole’s work and time in the sport shows in all his stories and it’s the physical details that demonstrate this. For example, from his novel Pound for Pound: “It was there in the stink and spit that he learned to grow the nails on his thumbs and forefingers longer than on his other fingers, to better snag and remove adhesive tape from his hand wraps after sparring.”

No one who had not lived the fight game could include something like this and lend such authentic texture to his writing. Another example from Pound for Pound:

“Dan had seen it before. You never knew when the cotton mouth or the empty ass would hit you. Fighters with twenty-five fights would sometimes have to take a scare pee after they’d been gloved and were already making their way to the ring. When it happened, Dan would pull a quick U-turn at ringside and run the boy back to the dressing room. He’d have to pull the boy’s shorts and cup down, then aim his shriveled dick so he wouldn’t piss on his shoes.”

While fear before a fight is intuitive, the details of how a trainer deals with it can come only from a writer who has seen young boxers experience it. And the slang Toole uses, such as “empty ass,” is the vocabulary of those initiated into the fight game.

Toole’s stories are packed with details like these, with the fabric of a fighter’s life that remains invisible to those of us who see only what transpires from the opening bell to the referee raising the winner’s arm. And to his credit, Toole doesn’t romanticize his insider knowledge. He is honest about the hardships, the pain, the consequences, and also the glory, when, and if, it comes.

But what Toole is most honest about is race. It must be remembered that boxing, like other sports, has an unfortunate history of racism, but the modern game has a strong streak of egalitarianism which the casual fight fan may not see. In Toole’s stories, different races mix and mingle because in boxing one is far less defined by skin color or ethnicity than he is by his wits and skills inside the ropes. Being a member of “the fancy,” as Toole calls the boxing community, can at times transcend racial tensions and prejudice. From the story “Rope Burns”:

“The South was still de facto Jim Crow territory in the late sixties when Mac and Cannonball traveled to places like Houston or even DC. Whites would put up a stink sometimes, but they’d shut up once they knew they were messing with members of the fancy. Many would even settle down to praise Joe Louis, Henry Armstrong, and Sugar Ray, for whom they had great respect and of whom they were genuine fans.”

Toole addresses the less savory side as well. In “Fighting in Philly,” a story set in my home town which has both a rich boxing history and a sometimes difficult racial past, the main character, a cornerman, muses on the tendency of white fans to want a white champion:

“He knew how badly white people wanted a white heavyweight champ, how much they’d pay. He wished they’d had a white boy, too. He would be able to help his own kids that way, help them get a leg up …”

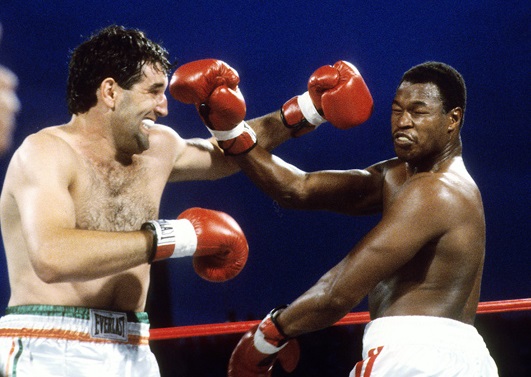

This passage brings up memories of historic fights such as Larry Holmes vs Gerry Cooney, when America tried to will a “Great White Hope” to victory in the glamour division. But within a page of that same tale, Toole turns to the more fair-minded side of race in boxing in a moment when a boxer returns to his former training team, “his black daddy and his white grandpa.”

More often than not in Toole’s stories, race is brought up in an affectionate way. Jokes are good-natured because characters respect each other. There are many scenes where a character of one race immerses himself in the culture of others. This is especially prominent given that much of Toole’s writing is set in Southern California, where black fighters eat burritos after tournaments and Latinos hang out in pubs and celebrate wins with their Irish trainers. His characters aren’t saints, but they frequently overcome a particular hurdle too many people still stumble over, and it is the culture of boxing that allows them to do so.

Toole’s short stories stand out from his novel. They are polished and precise. Since they don’t glorify the sport or apotheosize fighters, they read more like the work of Raymond Carver than Hemingway. Pound for Pound, Toole’s only novel, is worth reading, though it is a deeply flawed work published after the author’s death. Toole’s heart gave out before he could complete the manuscript and his agent worked on 900 pages of material to shape it into a novel. As a result, Pound for Pound lacks focus and scenes read as bloated with minor characters getting too much time on the page. But it’s still clearly the work of a writer who knew every aspect of the fight game, and for that reason it is worth reading.

F. X. Toole’s literary life was a short one, but he put decades of boxing knowledge into rich characters and perfectly controlled prose. Reading him makes one feel a part of “the fancy” for a few hundred pages, and there are few better compliments to pay a boxing writer than that. — Joshua Isard