Punching From The Shadows

In labeling Punching from the Shadows a memoir, Glen Sharp might be selling short his autobiographical work. More than a memoir, Sharp presents in his book a thorough and engrossing examination of his relationship with boxing. This he does via a detailed blow-by-blow account of the contest between a clearly rational mind–his own–and boxing, a discipline which, as Norman Mailer once put it, mocks the effort of the understanding to approach it.

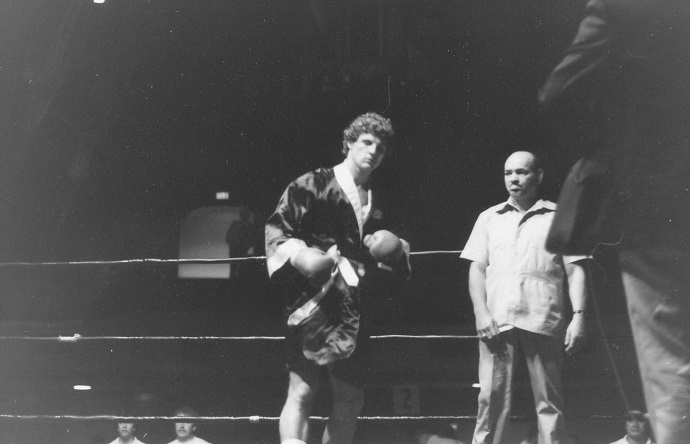

As a trained economist, Sharp molded his mind into a calculating one, and as such is surely aware of the potential problems of drawing conclusions from an inappropriately small sample size. However, the pointed insights that make up the bulk of Punching from the Shadows not only excuse this shortcoming, but actually make a strong case for Sharp’s conclusions. If his final record of one win against two defeats — accrued over a matter of months in 1982–seems paltry, Sharp’s recounting of his short foray into prizefighting is vivid, fun, and piercing, making the most of his ring experience, which, while limited, shaped the rest of his life in a deep and undeniable way.

Perhaps more important is the fact that Sharp comes across as entirely genuine in his desire to discover what made him pursue boxing in the first place, and to understand how much of his failure as a prizefighter was due to his own choices, how much to his limitations, and how much to just plain bad luck. His clear-headed assessment leaves no room for self-pity, but what makes it a worthwhile read is that it’s delivered in the form of an apologia for boxing not only as sport, but as an aesthetic pursuit as valid as any of the arts. “Boxing is not pure violence,” writes Sharp, “[but] the dramatic, at times even elegant, artistic rendering of violence.”

If the unexamined life is not worth living, surely such examination is only as valid as the degree to which it is pursued with humility and honesty. Sharp is acutely aware that nothing but the truth will do if he is to arrive at a satisfying explanation for his relationship with prizefighting. “I hope… you find me to be a pretty good storyteller, because I sure wasn’t much of a fighter,” he writes in the preface, in a phrase that first strikes one as little more than a self-deprecating jab, but which in hindsight is a perfect representation of his book: truthful, unambiguous, self-querying. Moreover, it evidences Sharp’s belief that we can only know who we are by honestly telling our own story: not one that pleases or comforts us, but one that satisfies our craving for understanding.

Sharp’s relationship with prizefighting began after a hurried amateur career that saw him turn pro to avoid having to get a “real job.” To his great surprise, things went pretty well in the beginning: “I didn’t deserve what was happening. I had not taken boxing as seriously as I should have as an amateur, and just a month or so after I had decided to apply myself, I was going to be trained by a former world champion and have a manager to operate the business end of my career.”

When the pieces fall into place so easily, success seems predetermined, almost unavoidable. However, as Sharp would soon discover, there are no shortcuts to cover the gap separating a novice from a world-class talent. In this regard his apprenticeship began in earnest when he started sparring with Yaqui Lopez, one of the best light heavyweights to never win a world title. Of his first sparring session, Sharp writes: “I had never seen so many right hands in all my life. If I threw a jab, Yaqui would throw a right hand over it. If I tried to hook, he threw a right hand inside of it. If I threw a right hand myself, he would block it or slip it and counter with a right hand of his own. I ate so many right hands that first day I didn’t need dinner when I got home at night.”

The experience showed Sharp his exact spot in the pecking order, but if anything, meeting Yaqui cemented his desire to fight. Getting to know Yaqui outside the ring also showed him precisely what it takes to become a decent boxer, never mind a world title challenger: “Yaqui appreciated boxing for the act itself. I had always loved boxing despite how much work was required, but Yaqui loved boxing because of the work.”

This is what led Sharp to realise that to become really good at something demands total dedication: “Attraction without commitment is not love; it is only desire. I had a desire to box, but I did not love boxing enough to give myself to it.” But if Sharp’s commitment to boxing might not have been as total as Yaqui’s, that doesn’t mean he wasn’t learning as much as he could. During his short career, Sharp flirted with no less than three fighting styles, each with its own idiosyncrasies, advantages, and disadvantages, struggling to adapt them to his own propensities and physical attributes.

His first trainer, Hall of Fame middleweight champion Carl “Bobo” Olson, compelled him to adopt the Benton (or “Philly”) shell. Sharp later realized the Burnett shell was a better fit, even if he still reverted occasionally to the chaotic offensive style that got him through his amateur career, a style which relied heavily on his powerful left hook.

“Not thinking of oneself as being heroic is a safe way to live, but it does not necessarily make for the best stories we can tell about ourselves,” Sharp writes, but even more significant is his conclusion that heroism is not to be equated with carelessness. Upon facing the reality of regular beatings by Lopez, Sharp began a quest to find his best self in the ring, something which would require him to focus on defense at least as much as he did on offense, even if it meant negating a part of him that he once thought of as essential. The shift was successful to an extent, with Sharp even scoring a knockdown towards the end of his sparring relationship with Yaqui. This progress in sparring represented a significant step forward in Sharp’s mission to regard himself with conviction as a prizefighter, despite the fact his meager earnings said otherwise, despite the rational part of his mind disagreeing with his chosen profession, and despite his father’s quiet disapproval of his trade.

“When Terry Malloy said ‘I coulda been a contender, I coulda been somebody,’ he is talking about being someone to himself,” Sharp observes, recalling the famous character from On The Waterfront, and thus defining his boxing excursion as a journey of self-realisation. Unfortunately for him, Olson’s stubborn recommendation of the Benton shell, Sharp’s sense of guilt and confusion at not getting much success out of it, and his attempt to mix in other elements into his fighting style all conspired against him in his third professional fight, the one he was most confident of winning:

“…with all the adrenaline in my blood system, the situation was much more tense, and my brain locked up I was not able to think as clearly as I could while not under pressure. I could sense the precarious position I had placed my head in. Having programmed myself to fight defensively but having that authority questioned by my natural desire for a more physical fight, I was stuck in no man’s land, with no ability to understand why.”

In less than three rounds, Sharp experienced the complete effacement of any validation he had struggled so hard to earn in the gym. The blow was so devastating that it moved him to retire from the sport, even if Lopez tried to talk him out of it:

“[Yaqui] pleaded with me not to stop. He told me I was going to make some money. He turned away from me as I said to him that my lack of aggressiveness would always be a hindrance to my boxing. He did not want to look at me as I lied to him, he did not want to witness me lying to myself. He did not want to see me as not only too cowardly to keep fighting, but too cowardly to even admit why I was running away. That hurt worse than any time he ever hit me.”

Sharp went on to get a “real job” and live a relatively comfortable life, and when the siren call of boxing tempted him again, life found a way of impeding a return to the ring. But the insights Sharp gained about the sport and about himself would nurture his intellect for ever after. Eventually he found literature, and fell in love with it just as he had with boxing; he became a writer, and took the final step in his journey of self-discovery by documenting his fighting career and what he had learned from it. So no, Sharp didn’t become a world-class fighter; in fact, at no point in his life did he make a living as a prizefighter. Fortunately, he did become a very good storyteller; Punching from the Shadows is proof of that. –Rafael Garcia