Ring 10: A Glimmer Of Light In A Dark And Lonely Sport

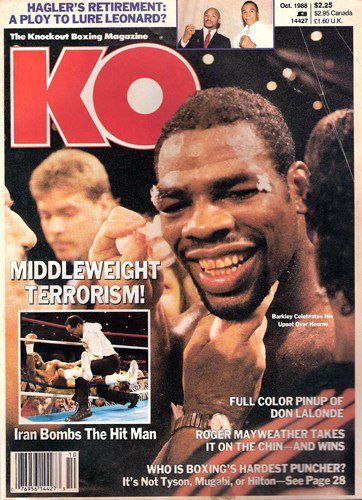

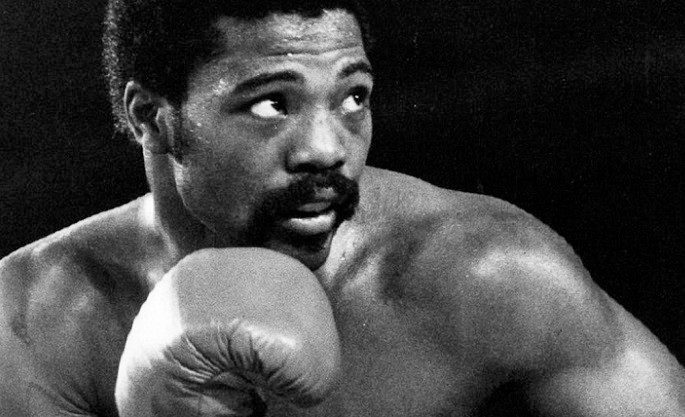

It’s been a long time now, almost three decades, since Iran Barkley became an overnight sensation, when the boxer known as “The Blade” stopped Thomas Hearns in three rounds and won the WBC middleweight title. He was 28-years-old and on that night in Las Vegas, he was on top of the world.

The next year, Barkley rumbled with Roberto Duran in a grueling 12-round battle that was the Fight Of The Year, but it ended in a split decision for the Panamanian legend. He later fought Michael Nunn in 1989 and Nigel Benn in 1990, suffering defeat in both title fights. But in 1992 he came back to stop Darrin Van Horn and then challenged Hearns at light heavyweight and became the only man to prevail twice against “The Motor City Cobra.”

One might think that after winning world titles and facing some of his era’s most popular fighters, Barkley could look forward to a comfortable after-boxing life. At the very least, one would expect his retirement years to be a level above the poverty of his youth when he lived in the squalid housing projects of the Bronx. But despite career earnings of roughly $5 million, soon enough Barkely found himself in a worse situation than ever before, homeless and sleeping in a New York subway station with nothing to his name but a bag of clothes and the title belt he won from Hearns. Friends eventually helped Iran out and paid for some hotel rooms, but needless to say, this was far from the situation Barkley had imagined for himself when he hung up his gloves.

It was a group of boxing industry veterans, organized as the Ring 10 Boxing Foundation of New York, who helped Barkley to eventually get back on his feet. They provided support, found him an apartment, and essentially gave him a new lease on life, restoring the dignity of a former boxing champion.

On a balmy October evening in New York, I met Iran Barkley for the first time. Wearing a black shirt and a gold chain around his neck, “The Blade” is still an imposing figure, although now he looks more like a heavyweight than a middleweight. He still commands attention; people turned as he entered the restaurant where we met. He is soft-spoken, and he shook my hand gently to introduce himself. “I’m Iran,” he said with a warm smile.

Barkley was there to attend a Ring 10 meeting. He and a few former boxers are Ring 10 board members and attend the organization’s monthly meetings in the Bronx. That night was the group’s first after their annual September fundraiser, the seventh such event since the group’s founding in 2010. One of the agenda items for the evening was to go through the financial records from the event. The board spent the first few minutes of the meeting dissecting a five hundred dollar discrepancy in the records kept by two different officers. For an organization that needs every dime it can get to fund its mission, five hundred bucks is kind of a big deal.

“We can’t lose,” comments Ring 10 founder Matt Farrago as the group goes over the numbers. “We may not win that much, but we can’t lose.”

While all board members agreed that the September 24th event was worthwhile and that they would like to do it again next year, some lamented the difficulty of getting big name boxers to attend. This year several of the invited guests backed out at the last minute, forcing Ring 10 to absorb the costs of unused hotel rooms and travel expenses. As non-profit organizations like Ring 10 have to compete with other charitable causes for people’s good will and generosity, the attendance of boxing celebrities is critical to attracting more people and securing more donations.

Ring 10’s challenges are symptomatic of the struggles of the largely disjointed Ring organizations in the United States. Ring chapters were formed across the country to provide assistance to retired boxers, but of course it’s difficult to carry out a benevolent mission when resources are scarce. Ring chapters are generally underfunded and have limited options, but there is a steady stream of ex-boxers who need their help.

“What does a pro football player who’s put ten years into the sport have when he retires?” asks Farrago. “He has money and financial advisers. He’s probably got an education because football players receive scholarships and go to university. Where does a fighter come from? The streets. What does he have when he retires? Not nearly as much to fall back on.”

A lack of education makes boxers susceptible to exploitation in a sport where it’s every man for himself. And after retirement, many pugilists eventually end up where they came from, with their bank accounts empty and their houses, cars, and even families, gone, leaving the boxer truly alone, with nothing and no one to fall back on.

For the most part, the former boxers who have retired to relatively comfortable lives and are able to take care of themselves are those with a college degree. Farrago himself earned a bachelor’s degree from the State University of New York even while pursuing a professional boxing career as a middleweight. At 56, he has long since retired but it is clear he still loves the sport and he has dedicated himself to executing Ring 10’s mission while working a demanding full-time sales job. His work at Ring 10 is a labor of love that is unlikely to bring him any monetary rewards in the foreseeable future.

Funding for the noble cause of helping retired and injured boxers is hard to come by and whatever amount Ring 10 raises goes primarily to ex-boxers who are in dire need. Ring organizations rely on fundraisers to secure the money they need, but compared to other sports, boxing no longer appeals to a broad audience and hence Ring 10’s events do not attract big crowds, or the crowds that have deep pockets. Meanwhile, corporate sponsorships are elusive.

“Boxing is a lonely sport,” says Bruce Silverglade, who owns the famed Gleason’s Gym in Brooklyn and was an awardee in the recent Ring 10 fundraiser. “When you go into that ring, you’re all alone and that’s what boxing is. You’re alone, and not just in the ring, but also outside the ring. There is no support system.”

Like most industry veterans, including Farrago, Silverglade believes another reason boxers are exploited and overlooked is because of the absence of a national regulatory body. Unlike other sports leagues in America, boxing has no pay levels, no pensions, not even medical coverage requirements. States impose their own rules, but if they do so stringently, this only drives promoters and fight cards to go elsewhere. Thus boxers must fend for themselves and make sure there is enough money left for when they walk away from the ring for good. But many are unable to do just that.

Silverglade believes the lack of support, not just for Ring organizations but for boxing in general, reflects the political and social reality in America. Boxers come from the lowest economic class and are social outliers. “The people involved in boxing don’t come from a big voting bloc, so government agencies don’t want to spend money on them. There’s no return.”

Despite the seeming popularity of boxing for fitness, pugilism itself does not really have mass appeal beyond the biggest fights. Indeed, many who take up boxing for exercise do not even watch a boxing match, much less know the current crop of boxers.

“People don’t like the sport of boxing,” Silverglade notes. “People think it’s just violence. They don’t understand the benefits of boxing. That’s a marketing problem.” This perception inhibits the organizations which help boxers from raising significant amounts of cash to make a long-term sustainable impact on the athletes.

Even local boxing clubs and well-intentioned programs such as Gleason’s Gym’s “Give A Kid A Dream” can’t find ongoing support. “It gets zero dollars,” Silverglade laments. “Everybody will give you lip service, will tell you how great it is, but nobody will open their wallets.”

And if boxing programs that may one day produce the next world champion are getting no support, the chances of retired boxers getting it are even slimmer. Institutional sponsors are unlikely to see any return on investment from retired fighters, some of whom may not even be physically able to remember their sponsor’s name.

Because a national governing body is unlikely to be formed anytime soon and institutional support is not forthcoming, perhaps the solution lies within the industry itself. Payoffs for the top champions and boxing stars can be astronomical, with many millions earned for a single mega fight.

But for every Floyd Mayweather or Manny Pacquiao, there are thousands of lesser known boxers who will never see that level of financial success. Could the industry itself learn to better distribute the wealth to close the income gap?

“Mayweather made over $200 million from his fight with Pacquiao,” notes Silverglade. “So why not take just $1 million and give it to the undercard? If you make $199 million instead of $200 million, it’s not going to kill you.”

But boxing in America, which is controlled by just a handful of big players, is not built with altruism in mind. Silverglade notes that the industry does not care for even the most magnificent and successful boxer the moment he gets injured and stops fighting. “They don’t care,” says Silverglade. “They say, ‘Who’s next?’”

For this reason, boxers will continue to need organizations like Ring 10 because when there is no one else to turn to, this organization can provide some relief. Farrago says requests for assistance have grown, partly because of Ring 10’s online presence. Farrago diligently posts pictures of the group’s events and writes blog posts about its activities. To raise extra cash, Ring 10 sells t-shirts and beanies, and auctions off boxing memorabilia, such as the discarded hand wraps of famous fighters.

At any given time, the group helps 15 to 20 retired fighters across the United States, Farrago said. Assistance can be in the form of gift cards for groceries, or financial assistance for rent or medical costs. The group wants to do more, but resources are limited. To save money, Ring 10 operations are run out of Farrago’s home and no one receives a salary or allowance for their work in the organization. Everyone pays for their own dinner at the monthly board and members’ meetings.

Despite these constraints, however, Iran Barkley is just one of the ex-boxers Ring 10 has helped. Among the fighters who have received support is Wilfred Benitez, a champion and Hall of Famer who now lives in a shack in Puerto Rico and is being cared for by his sister. Similarly, Ring 10 sends monthly gift cards for groceries to former middleweight champion Gerald McClellan, who has been severely handicapped since his battle with Nigel Benn in 1995. And more recently Ring 10 provided assistance and collected donations on behalf of Magomed Abdusalamov, who was severely injured in his bout with Mike Perez in 2013.

Ring 10 also made sure it helped Howard Davis Jr. meet the cost of his chemotherapy and homeopathic treatments for lung cancer. In his final months in 2015, Davis was honored by Ring 10 with a replica of the four Golden Gloves pendants that were stolen from him years before. Davis passed away in December of that year but Farrago takes solace in the fact that Ring 10 helped him through the hardest fight of his life.

As the board meeting transitioned to the regular membership meeting, the discussion became more spirited since naturally there were more issues and unfinished business to attend to beyond the most recent fundraising event. Thankfully, the $500 bookkeeping discrepancy was resolved, but once one fire is put out, two or three more must be dealt with. In this way Ring 10 is a reflection of boxing as an industry. It is old-school and scrappy, reliant on the wit and grit of dedicated grass-roots volunteers, and survivors like Barkley.

But it’s a sad statement on boxing itself that the organization receives no ongoing financial aid from any of the sanctioning bodies or promotional companies which, it must be noted, profit handsomely from boxing and from the sacrifices of its injured athletes. Should it be so difficult for Ring 10 to secure financing from the sport it is trying to serve? Couldn’t some of boxing’s big players and more successful champions offer some help? Hopefully such support will transpire in the near future. But in the meantime, like the fighters it serves, Ring 10 is an organization with a big heart, one determined to keep going no matter what, and provide much needed assistance and dignity for boxing’s wounded warriors. — Sheila Oviedo

For more information on Ring 10, please visit: http://ring10ny.com/

Maybe when a fighter gets their boxing licence they could sign up to offer a percentage of their purse money to Ring 10.