The Darker Road Of Raging Bull

“And then I was hitting Pete as hard as I could and Vickie was screaming, and I was beating Vickie and then raping Viola, and I found myself crying, sobbing, and I didn’t know what the hell was happening. I thought I was going nuts, that I was losing my mind.”

Welcome to the world of Jake LaMotta.

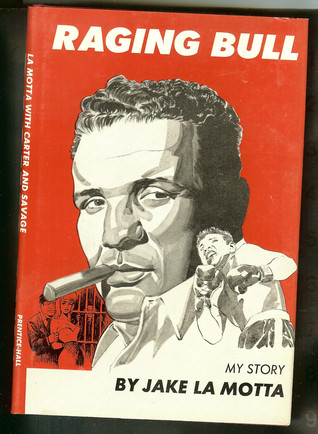

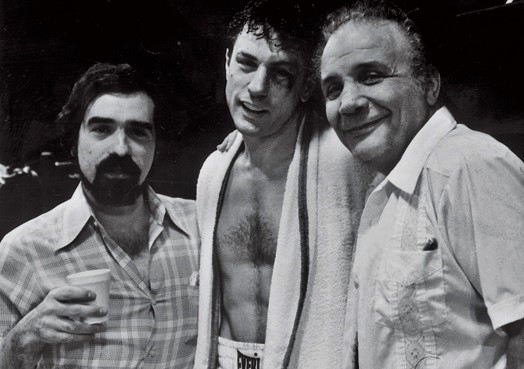

While Martin Scorsese’s 1980 film adaptation of LaMotta’s autobiography, Raging Bull, was critically acclaimed for its visceral depiction of one of the darkest individuals to ever enter the prize ring, there was no way Hollywood could depict all the shocking material in “The Bronx Bull’s” deeply disturbing memoir. Nor would Scorsese likely even want to recreate such a tale for the screen, with the middleweight champion’s many heinous acts simply too repulsive for most movie-goers. What viewers get instead, from a film that is rightfully regarded as a classic of American cinema, is a mere glimpse of all the lurid contents of LaMotta’s detailed account of a man plagued by inner rage and insecurity, a man whose self-destructive nature eventually drove everyone and everything from him and almost destroyed his life.

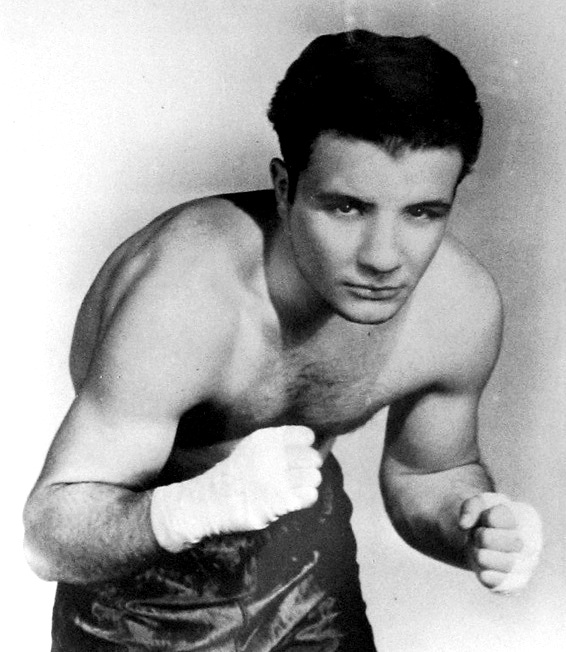

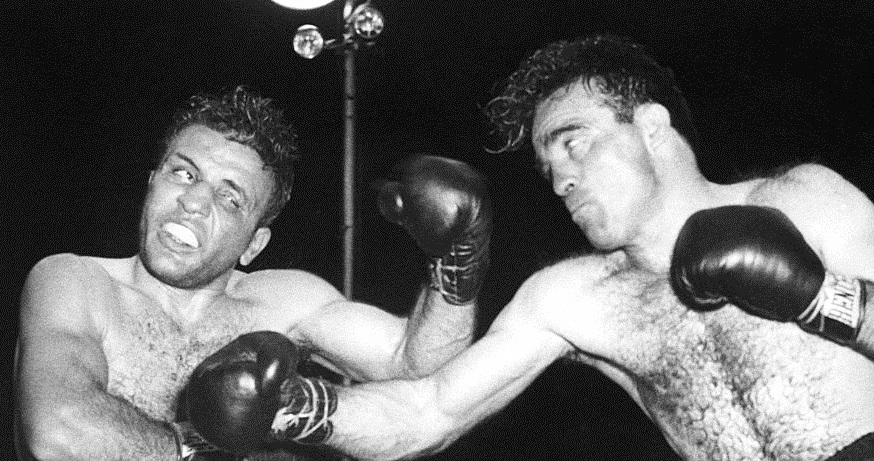

But it can’t be forgotten that Jake’s darkest attributes also allowed him to become the champion and ring legend he was. His thirst for violence and unhinged rage defined his whirlwind approach inside the squared circle, while his simmering self-hatred enabled him to withstand some of the most brutal punishment any fighter has ever had to endure. “I fought like I didn’t deserve to live,” said LaMotta in a 1970 interview with Peter Heller. “I took unnecessary punishment when I was fighting. I didn’t realize it but subconsciously I was trying to punish myself.”

While it does not justify his violent actions outside the ring, LaMotta’s autobiography gives you a look at the external forces that molded the monster: the extreme poverty, the abusive father, and the otherwise loveless nature of his upbringing. At one point Jake recollects running home crying from school after having been beaten up, his lunch money stolen by bullies. But instead of understanding and sympathy, LaMotta was greeted by a vicious slap across the face from his father who told young Jake if he came home crying in the future he could expect an even worse beating. Then his father handed him an icepick and told him: “Hit ’em first. And hit ’em hard.” In the years to come, whether it be with an icepick or his fists, violence would serve as Jake’s first and only way to control his surroundings.

Such was the beginning of a brutal, not to mention criminal, childhood and adolescence, marred by theft, assault, and nearly murder. LaMotta’s first unforgivable deed is described in chapter one of the memoir when he beats a neighborhood bookie by the name of Harry Gordon into a coma just to rob him of his earnings. “I wanted to kill him I was so mad that he was still up,” LaMotta recalls, “and I began to hit him again and again. And he finally collapsed.” Jake believed he had murdered Gordon and it wasn’t until after he finally won the world middleweight title from Marcel Cerdan, fully eleven years later, that he learned Gordon had in fact survived the assault.

Like LaMotta’s many other crimes and heinous acts, this attack manifested itself as one of many demons which tortured Jake throughout his life. His haunted and miserable existence was further compounded by the fact that he was virtually incapable of expressing his true thoughts and feelings with anyone, much less repent for the acts he believes made him an animal and beyond all redemption.

But while LaMotta was an unrepentant sinner, one of the most important figures in his life was Father Joseph, the priest who first introduced the 16-year-old Coxsackie Reform School juvenile to the ring. Joseph, who is not portrayed in the film, represents the nurturing father-figure Jake never had growing up, and the closest anyone ever got to remotely earning Jake’s trust. But despite numerous heartfelt efforts, even the priest is unable to penetrate the armor of LaMotta who, when confronted during his last day at Coxsackie about what is really troubling him, tells Father Joseph, “You don’t understand how it is. I can’t trust anybody, I never learned how.” Jake’s main defense mechanism was to trust no one. And given the environment he grew up in, it’s not at all surprising.

Another pivotal character not depicted in the film is Pete Savage, LaMotta’s closest friend since childhood, who co-wrote the autobiography. Pete largely occupies the role that Joey LaMotta takes in the movie, as it is Pete, not Joey, who staves off the mafia’s attempts to control Jake, who stands up for his wife, Vickie, and who ultimately is accosted by LaMotta due to Jake’s uncontrollable jealousy. Joey LaMotta’s actual role in his brother’s personal life is not nearly as pivotal as portrayed in the film; in the book he mainly consults Jake on matters pertaining to inside the ring rather than outside of it.

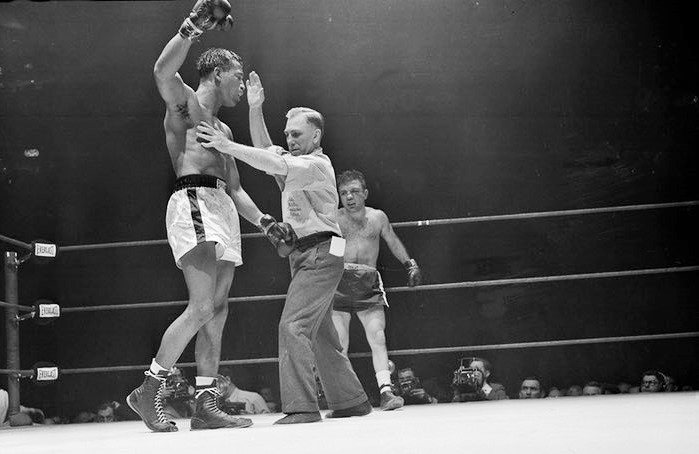

A key difference between Pete in real life and Joey in Scorsese’s Oscar-winning classic is that Pete does not yield to the mob’s insatiable demands. It’s no secret that the mafia held the keys to the popular “Bronx Bull” getting an overdue shot at the middleweight title, but in the end it was Jake alone who finally agreed to take a dive against Billy Fox in exchange for a title shot. It was Jake who, despite his hatred for the mob, decided he would take whatever means was necessary to win the championship of the world. This, after all, was the one, true passion that LaMotta sought out from an early age. “There was only one thing I wanted out of life,” states Jake in his memoir. “That was to be the champ. I was going to be the champ no matter how.”

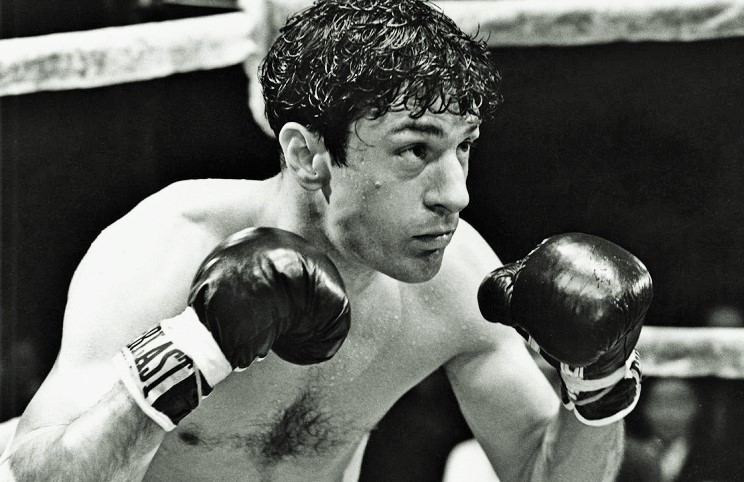

Similar to the film, Raging Bull the book describes how Jake’s demons eventually catch up to him. In perhaps Robert DeNiro’s most iconic three minutes on screen, and the scene that almost certainly earned him the Academy Award for Best Actor in 1980, an overweight, spiritless, and bare-fisted LaMotta pounds a wall in his jail cell with every bit of ferocity he once exhibited in the ring. This pinnacle moment, as in the movie, marks the climax of the book. It was the moment of LaMotta’s spiritual awakening, and while it in no way condones his vicious actions of the past, it is the turning point, the only reason Jake went on to find some peace in life.

“I’ve done a lot of bad things in life, Joey,” DeNiro tells Joe Pesci in the film as the LaMotta brothers sit in the dressing room after another loss to Sugar Ray Robinson. “Maybe it’s coming back to me.”

It’s a subtle line in the movie, easily overlooked, but it carries great weight in the pages of LaMotta’s autobiography. The tale the former champion tells is that of a deeply disturbed individual who lacks the ability to repent for his sins. But this unrepentant nature took its toll on LaMotta’s spirit, and the retribution Jake endured inside the ring is nothing compared to the demons that haunted him outside of it.

Raging Bull the book gives all the sordid and graphic details the film simply cannot provide in a deeply engrossing depiction of one of boxing’s most celebrated icons. The effect on the reader might well be pure repulsion for the vile and brutal nature of Jake’s actions: the rape, the violence, the misogyny. But for those who choose to delve deeper into LaMotta’s twisted psyche and, dare I say, attempt to empathize with his inner torment, Raging Bull will drag you down one of the darker roads to retribution that you likely have ever experienced.

It’s a story whose central theme is memorably summed up in the biblical quote from Scorsese’s final title card of the film: “Once I was blind and now I can see.” But where the movie mostly focuses on LaMotta the bull, the book also vivdly depicts LaMotta the prey, the man whose pain and rage eventually stripped him of everything he feared losing: his family, his mind, and his dignity. As great as Scorcese’s film is, Jake LaMotta’s torturous and tumultuous road towards self-acceptance could never be better captured than in his autobiography, Raging Bull. — Alden Chodash

A spirited, well-written review of both book and movie. Great work by this fine young writer, Alden Chodash.