That Sad, Empty Feeling

It’s stating the obvious to note that boxing is the most brutal and unforgiving of all sports, but knowing this did not mitigate the sadness of seeing a once-splendid athletic talent and proud champion humbled in a fight that should never have happened. 2015 will be remembered for a number of significant events, but the image of Roy Jones Jr. flat on his face courtesy of a series of power punches from cruiserweight Enzo Maccarinelli will be among the most indelible from this past year. Deflating? Dispiriting? Disturbing? Of course. Shocking? Sadly, not at all.

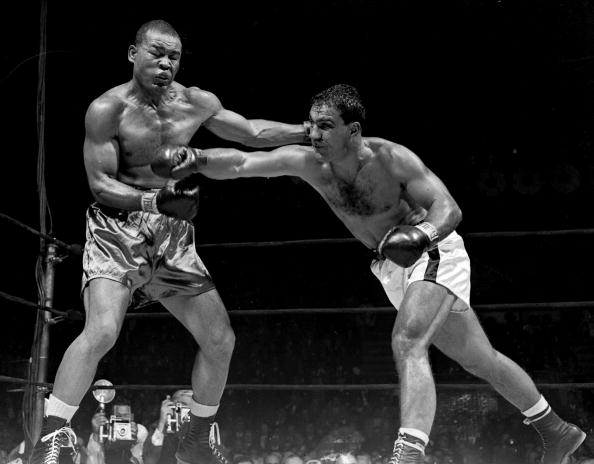

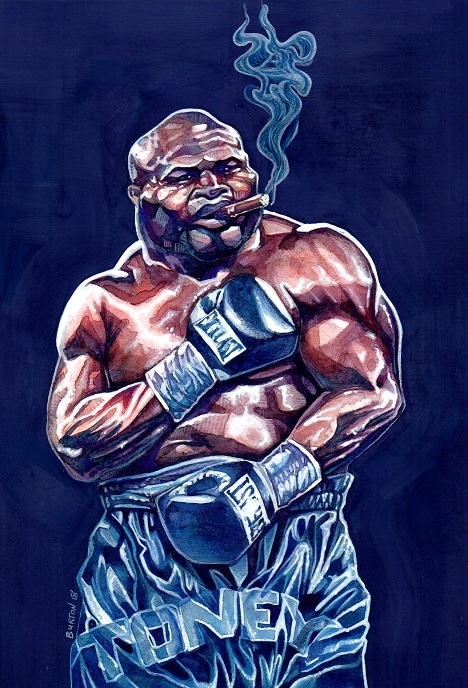

No doubt many who witnessed this debacle of a boxing match in Moscow had flashbacks to when Jones was young and vibrant and still gifted with the reflexes of a wildcat. At the height of his career, when he overwhelmed with ease legit champions such as Bernard Hopkins, James Toney, Virgil Hill and Mike McCallum, his boundless stamina and astonishing quickness were a sight to behold. But Jones, like the rest of us, is only human. His athletic gifts eroded by time, the end of his prime was marked by shocking defeats to Antonio Tarver and Glen Johnson. But that was more than a decade ago.

One can only speculate on Jones’ financial situation and whether money is the main motivation in his refusal to retire. If it is, that’s a terrible shame, as Jones had to know he was nearing the end when he collected sizable paydays against Joe Calzaghe and Felix Trinidad. Then came three losses in a row, one of them a first round stoppage to unheralded Danny Green, another a brutal knockout defeat to Denis Lebedev in 2011. At that point all sensible observers assumed retirement had finally come; how bizarre to realize he had won eight in a row against feeble opposition before falling to Maccarinelli. We can only hope that this is, finally, the end.

In a riveting in-depth profile by Brin-Jonathan Butler, that revealed both the horrific extent of the abuse Roy Jones Jr. endured at the hands of his father, and the fact his knees are so shot he is unable to do roadwork, the former champion states that history, and a desire to fulfill God’s plan, are his motivations, not money. If true, this puts him in select company; the vast majority of boxers who hang around for too long are motivated by a need for cash, even if they had made millions during their glory years.

Joe Louis, the man some regard as the greatest heavyweight boxer of all time, is perhaps the most poignant example. At the age of 35, and after having donated much of his ring earnings to help his country during World War II, “Joltin’ Joe” announced his retirement in 1948 after winning his rematch with Jersey Joe Walcott. He then discovered he owed the government vast sums in unpaid taxes.

Louis tried to regain the championship from new titlist Ezzard Charles in 1950, but it was too late: time had robbed him of his sharpness, had shackled those once deadly fists in heavy chains. After the fight, a hurting and exhausted Louis required help getting dressed and none other than Sugar Ray Robinson slipped Joe’s shoes onto his weary feet. He was led out of Yankee Stadium by friends, his final statement to the press a promise to never box again. Two months later he was back in the ring. Money woes forced him to keep fighting before Rocky Marciano finally knocked him out the following year.

If helping an aged Louis get dressed after a humbling defeat made an impression on Sugar Ray, it was not of the lasting kind. But he was ringside for Joe’s loss to Marciano and that night told legendary scribe Barney Nagler, “That’s never going to happen to me.” He was wrong. Robinson retired numerous times, only to keep coming back. His last fight was a sad ten round loss to Joey Archer when he was 44-years-old and all the magic was long gone. Jones, it should be noted, is 47.

Muhammad Ali still had plenty in his bank account when he returned to the ring at the age of 38, but to keep living the high life with his entourage and family, some extra millions were required. The case of “The Greatest” is unique in that there in fact was huge demand for his return. Despite it being obvious to any serious observer that Ali’s once astonishing skills were no more, he remained the biggest draw in the game and received a record high payday when he challenged Larry Holmes for the title in 1980. But even after being battered by his former sparring partner for ten pathetically one-sided rounds, Ali refused to quit. Instead he suffered a final defeat to contender Trevor Berbick the following year, that match taking place in the Bahamas because no athletic commission in America would grant Ali a license to fight.

That parallels the recent Jones fiasco in that Roy’s match with Maccarinelli, which might have faced opposition from any responsible athletic commission in the U.S., took place in Russia, the same country that allowed a 62-year-old Mickey Rourke to fight. The fact Jones recently became a Russian citizen perhaps paves the way for future matches in that country, despite last month’s knockout defeat. Let’s hope that’s not the case.

Ali was 39 when he finally called it quits, far too late to avoid the ravages of Parkinson’s Syndrome. But back then it was considered strange and supremely unhealthy for any boxer to compete much past the age of 35. Now boxing has its own unofficial “Seniors’ Tour,” with numerous fighters continuing to battle well into their 40’s.

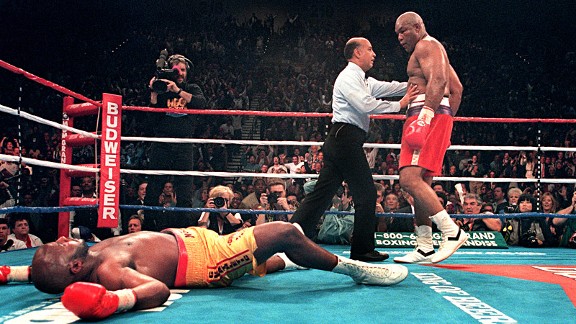

No doubt George Foreman has much to do with that. He returned to boxing in 1987 at the age of 39, after a decade-long layoff, and absolutely no one took his comeback seriously. But there he was four years later, challenging Evander Holyfield for the world title and earning a huge $12.5 million dollar payday. And there he was again in 1994, knocking out Michael Moorer with one right-handed clout to become champion again.

Ever since it’s been even more difficult to discourage aging champions from entering the ring. After all, Foreman suffered losses to Holyfield and Tommy Morrison before he reached the summit against Moorer at the age of 45. And now we have Bernard Hopkins winning titles at 48 and threatening to compete past the half-decade mark. Perhaps Hopkins’ success, notwithstanding his one-sided defeat to Sergey Kovalev last year, is part of Roy’s stubborn refusal to finally walk away.

Thus, the list of ex-champs who keep going despite faded reflexes and creaky joints seems to only get longer. Holyfield himself proved to be one of the most stubborn, refusing to officially call it quits until he was 52-years-old. Then we had the sad spectacle of Erik Morales taking beatings from the much younger Danny Garcia. Defying all common sense, Shane Mosley continues to fight, having won a match last month in Panama. And believe it or not, a 47-year-old James Toney will be shuffling his way to a boxing ring later this month in Ottawa and all involved should be ashamed of themselves.

Missing in all this is that old-fashioned thing we used to call dignity. What made seeing Jones on the canvas after absorbing Maccarinelli’s crude bombs upsetting wasn’t just one’s concerns about the older man’s health, but the ugly spectacle of a once proud and supremely talented boxer looking inept and overwhelmed against a man who, in his prime, Roy would have dominated with ease. What Jones, Hopkins, and all the other aging warriors appear unable to appreciate is that there’s nothing noble in stubbornly lacing up the gloves and battling on in a young man’s game.

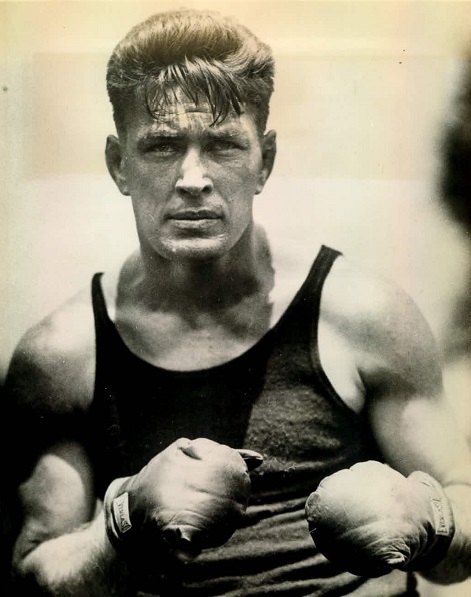

How much more admirable it is when a champion retains a degree of modesty and bows out while still at, or near, the top, and leaves the fighting to younger fists. Take former heavyweight champion James J. Braddock, “The Cinderella Man,” who finished his career at 33 with a thrilling decision win in front of a sold-out crowd over top contender Tommy Farr. Or how about Gene Tunney, who in 1928 walked away from boxing while still the heavyweight champion of the world and at only 31 years of age. Or, to take a more recent example, undefeated super-middleweight champion Joe Calzaghe, who retired at 36 while still in possession of his world title belts. Of course the latest and, should he in fact stay retired, the ultimate exemplar considering all the money he made, is Floyd Mayweather Jr.

All four champions could have kept fighting, could have collected big paydays. Instead, they took stock and decided, “Enough.” How we all wish Roy Jones Jr. had made the same wise decision sometime prior to this past month, and thus spared himself a sordid defeat far away in Russia. And spared the rest of us, when we saw him lying in a heap at Enzo Maccarinelli’s feet, that sad, empty feeling. — Robert Portis

Brilliant article mate.

Indeed, what ever happened to dignity in this modern world of ours?