The Fight Fiction Of Robert E. Howard

In boxing, the past remains an ever present obsession. We display a reverence for history and the written word that borders on compulsion, poring through old newspapers, compiling lists of names and dates, catalogs of fights and fighters and clippings from old magazines. Even after a century of technological innovation — film, radio, television, and streaming — we still look to the writers, our scribes of the sweet science, for fresh insight into this ancient sport. We celebrate our bibliography from Homer and Virgil through to Byron and Whitman, from London and Hemingway to Mailer and Oates. There’s Nat Fleischer and Bert Sugar. There’s Egan and Liebling and Heinz, Talese, Plimpton, McIlvaney, and Hauser. On and on. But one name routinely goes missing from these lists: Robert E. Howard. One of the most popular pulp magazine writers of the 1920s and 30s, Howard’s accomplishments in boxing literature goes sadly unheralded. And we are the worse for the omission.

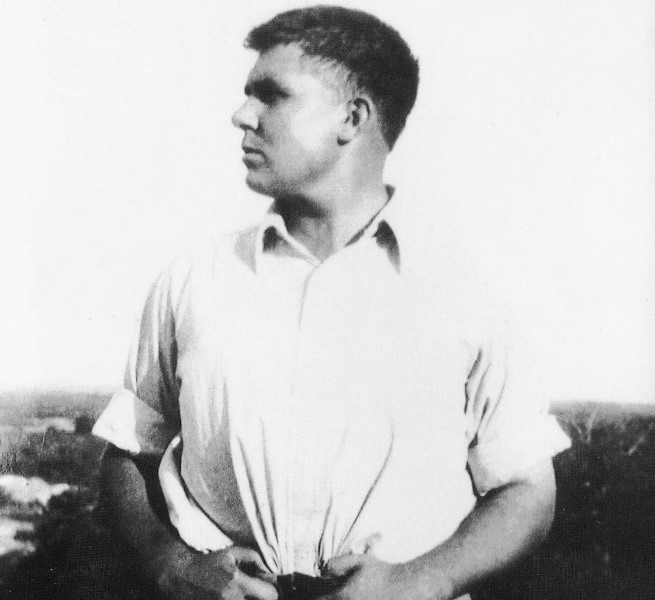

Born in Texas in 1906, Howard showed an early passion for stories. As a child he listened to older family members spin their Texas-sized yarns, instilling in him a love of storytelling. His world was broadened by the adventure tales of Jack London and Rudyard Kipling and he knew early that he wanted to be a writer, publishing his first stories while still in high school. During his teens, Howard also took up bodybuilding and boxing. He competed as an amateur boxer and remained an avid fan of the sport, continuing to spar throughout his adult life.

In 1925, Howard began publishing stories in pulp magazines such as the then-fledgling Weird Tales. Early stories involved werewolves and cavemen. Fueled by his interest in history and mythology, Howard began writing what would become known as the “sword and sorcery” subgenre of fiction. These stories spanned the globe and blended history with fantasy. He created heroes he could revisit and return to throughout multiple stories, including Kull the Conqueror, an Atlantean king; Solomon Kane, a Puritan swordsman; Bran Mok Morn, a Pict king, and Red Sonya of Rogatina.

In 1932, Robert E. Howard created his most enduring character: Conan the Barbarian, for whom Howard developed an entire fictional world, a land called Cimmeria, and even a fictional time, the Hyborian Age. This allowed Howard to indulge his love of history and myth while freeing him from the laborious and time-consuming research needed for historical fiction. He imbued the world of Conan with a sense of scope and scale practically unheard of in pulp stories, writing essays outlining Conan’s world, drawing up maps and creating gods, such as Crom. Conan has endured as a pop culture icon for almost a century through graphic novels, comic books, novelizations, and Hollywood adaptations. The character cemented sword and sorcery as a viable genre and influenced generations of fantasy writers, from Tolkien to George R. R. Martins.

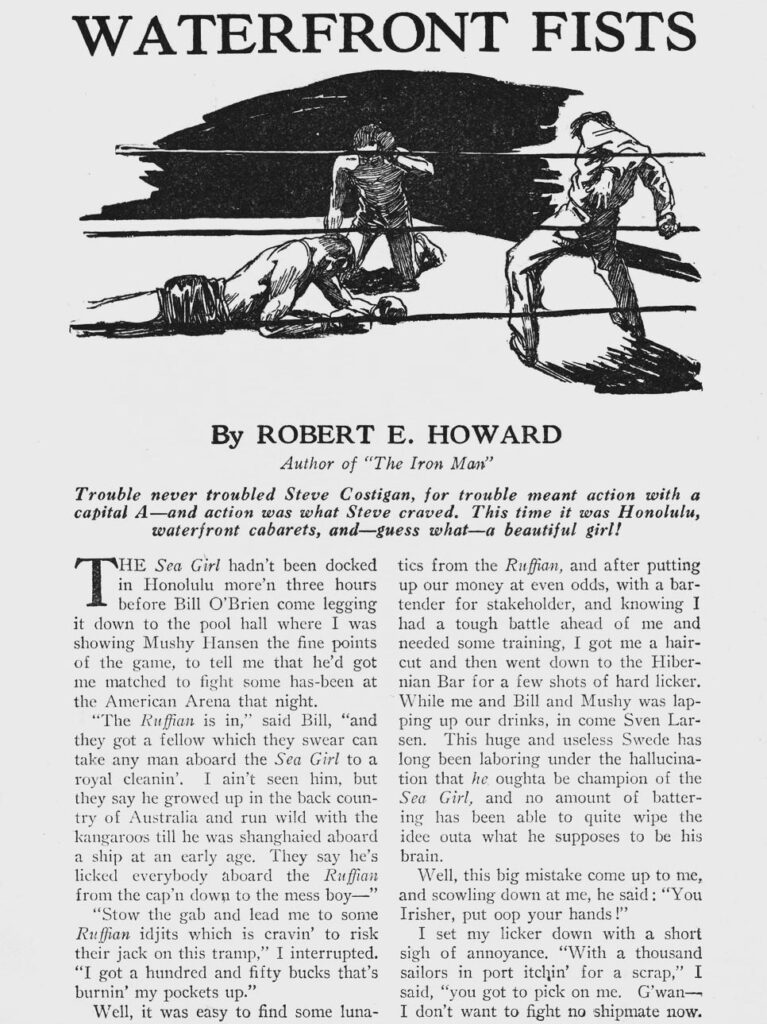

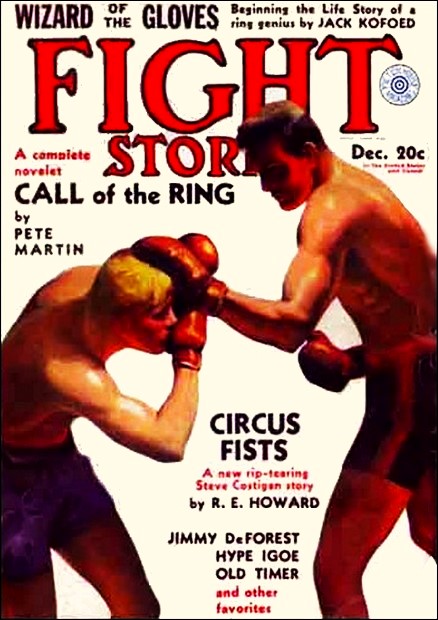

But while Conan would become Howard’s most enduring character, he wasn’t Howard’s most prolific. Instead, as fight fans will be interested to know, that honor goes to a wholly different Howard creation, a pugilist, Sailor Steve Costigan. Modeled partially on Howard, Costigan is a good-natured, Texas-born man with black Irish features who sails on the merchant ship The Sea Girl, “the fightenest ship on the seven seas.” Landing mostly in Asian ports, Costigan inevitably gets into brawl after bloody brawl. The first Sailor Steve Costigan story was published in 1929 and was a smash hit, pun intended, and Howard would write nearly forty Sailor Steve Costigan stories over the next five years. The success of these tales earned Howard, then only 23, enough income to stick to writing full time. Costigan’s episodic adventures would serve as a model for the later Conan stories, and the financial stability afforded by the Costigan yarns allowed Howard time to take on the more involved Conan project. Without the popularity of Sailor Steve Costigan, there would be no Conan the Barbarian.

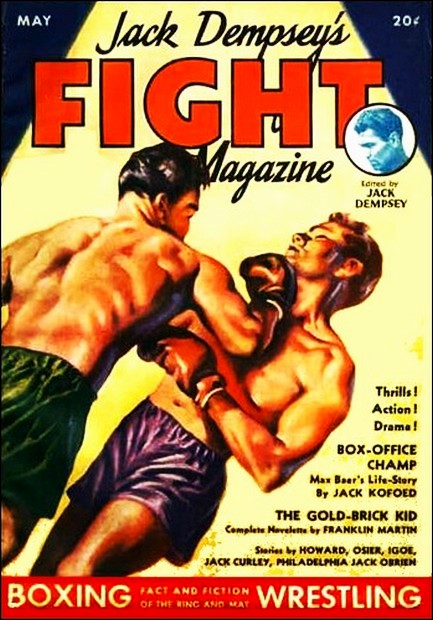

Given the precarious nature of the then-fledgling pulp markets, the publication history of Robert E. Howard’s Costigan stories would be somewhat convoluted. They first appeared in the pulp magazine Fight Stories, and soon branched out to its sister magazine, Action Stories. Costigan also appeared in the short-lived publication Jack Dempsey’s Fight Magazine. At one point, looking to expand the market for Costigan stories, Howard changed the character’s name to avoid conflict between rival publications. A boxing story about “Dennis Dorgan” – a sailor who just happens to be exactly the same in size, appearance, and temperament as Costigan – appeared in Magic Carpet Magazine in 1934. Howard wrote nearly a dozen Dennis Dorgan stories, but the magazine shuttered their doors before they could publish any more.

Howard came to boxing at an interesting point in history. The sport had been legalized in the United States but its outlaw past was still a recent memory. Boxing literature from around that time was Naturalist in style, realistic and a little grim. Jack London’s “A Piece of Steak” (1909), Ring Lardner’s “Champion” (1916), and Hemingway’s “Fifty Grand” (1927) portrayed the newly-established sport as corrupt and isolating. By contrast, Howard’s stories are lively and unconstrained, full of bravado and masculine vigor. They recall boxing’s outlaw zeal. It’s no surprise Howard found such success writing for the pulps. Society was becoming mechanized with a newly-formed “middle class” which no longer worked with their hands and masculinity was adopting crisis and anxiety as the new norm. Pulp magazines, with their exotic and scandalous stories of men relieved of that middle-class morality – sailors, cowboys, detectives, and pagan warriors – provided just enough sugar to coat that bitter pill.

The Costigan stories are fun and fast, lurid and absorbing tales of crime and violence. The action sometimes veers into slapstick, with wild battles that get less and less probable, with Costigan as likely to get into a barroom brawl as he was to enter the ring. Despite all the broken knuckles and cauliflowered ears, the tone remains light and breezy, with almost as much humor as there is action. One can easily imagine Depression-era readers basking in the fellow-feeling of these tall tales. Here’s how Howard begins “The Pit of the Serpent,” in which Cositgan fights a sailor named Bat Slade:

The minute I stepped ashore from the Sea Girl, I had a hunch that there would be trouble. This hunch was caused by seeing some of the crew of the Dauntless. The men on the Dauntless have disliked the Sea Girl’s crew ever since our skipper took their captain to a cleaning on the wharfs of Zanzibar—them being narrow-minded that way. They claimed that the old man had a knuckle-duster on his right, which is ridiculous and a dirty lie. He had it on his left.

Told from Costigan’s point of view, the stories are dripping with slang and vernacular and suffused with Costigan’s good-natured and down-home values, giving them a quality distinct from the unapologetically “hard-boiled” crime stories that filled the pulps. Degeneracy and corruption surrounds Costigan on the wharfs and waterfront dives he frequents, but it never seems to stain him. At least, not as he tells the story. But we understand that Sailor Steve Costigan is an unreliable narrator; he brags about his successes in hyperbolic terms while downplaying his indiscretions, like how much he’d had to drink or how much responsibility he bears for the fights he starts. With easy charm and likable humor, Costigan embodies that special strain of human nature that allows us to overlook our own faults, our guilt, and our culpability in the failures we ascribe to others.

After a while I found myself in a dance hall, and while it is kind of hazy just how I got there, I assure you I had not no great amount of liquor under my belt—some beer, a few whiskeys, a little brandy, and maybe a slug of wine for a chaser like. No, I was the perfect chevalier in all my actions, as was proven when I found myself dancing with the prettiest girl I have yet to see in Manila or elsewhere. She had red lips and black hair, and oh, what a face!

The seaports visited by Steve Costigan are diverse and Howard peppers his stories with accents and dialects and crisp dialogue. Rarely is a line of speech merely “said.” It gets whimpered or muttered or snarled or bellowed. He also relied on adjectives to convey tone and emotion. A fighter might grin savagely between punches while ringside a dame coos gently and her husband glares disapprovingly. If one is looking for a fault in the writing, the dialogue is sometimes a tad expositional, like a Bond villain needlessly explaining his schemes. Howard also leaned on dialogue to describe action, provide background information, and explain a character’s intentions. For Sailor Steve Costigan, there is practically no such thing as inner monologue; he is a man of action who tends to think out loud. Or, as is more often the case, he thinks with his fists.

“Hey you,” I accosted him politely, “where is that lousy first mate of yours?”

“Try and find out, you boneheaded mick,” he answered rudely. “What d’ya think uh that?”

“Chew on this awhile,” I growled, clouting him heartily in the mush, and for a few seconds a merry time was had by all. But pretty quick I smashed a right hook under his heart that took all the fight out of him, along with his wind.

During those same years, in more “literary” circles, the young Ernest Hemingway was advancing his “iceberg” theory of literature, that a story could be strengthened by what it omits. Like an iceberg, seven-eighths of a story could remain unspoken, submerged below the surface. But with Howard, those figures are reversed. These aren’t sensitive character studies full of subtlety and nuance and omission, but rough-and-tumble, no holds barred fight fiction. Everything’s on the surface: a new port, a new girl, a new fight. Resolution arrives with the dawn, when it’s time for Costigan to ship off yet again.

We met in the center of the ring like a thunder-clap, and his first lick split my left cauliflower, and my first clout laid his jaw open to the bone. After that it was slaughter and massacre.

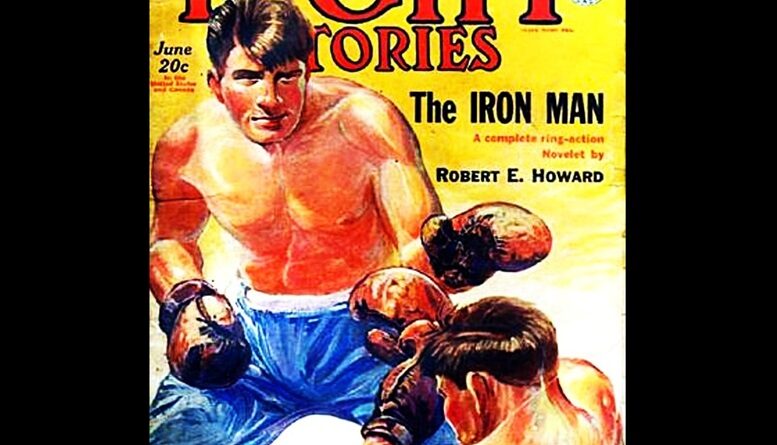

Howard did write a few boxing stories without Sailor Steve Costigan, and they are fairly standard but with wild titles appropriate for the pulps, such as “Crowd Horror,” actually a love story involving a fighter named Slade Costigan, and “The Apparition in the Prize Ring,” a surprisingly sensible yarn about a Black fighter, Ace Jessel, who idolizes the bare-knuckle fighter Tom Molyneaux. Another non-Costigan story, “The Iron Man,” shows Howard flexing his literary muscle with a longer “novelet” about “Iron” Mike Brennon.

A cannon-ball for a left and a thunderbolt for a right! A granite jaw, and chilled steel body! The ferocity of a tiger, and the greatest fighting heart that ever beat in an iron-ribbed breast! That was Mike Brennon, heavyweight contender.

As he did with his sword and sorcery stories, Howard blends fact and fiction, invoking real fighters and real fights. Joe Grim, Tom Sharkey, Joe Goddard, Battling Nelson, and Joe Choynski – “men who relied on their ruggedness to carry them through” – are mentioned alongside fictional fighters from Howard’s previous stories, such as Sailor Slade and Steve Costigan. Interestingly, Costigan gets described as a fighter “who never rated better than a second-class man, but who gave some first-raters terrific battles.”

Most of the boxing stories published during Howard’s lifetime appeared between 1929 and 1931, though a few would continue to be published in the years following. Howard was a man bursting with stories and after Costigan he moved on to Conan and later he tried his hand at other genres. He struggled with mysteries, tried writing racy stories for a publication called Spicy-Adventure Magazine, and found success writing westerns, where he created a likable hero, Breckinridge Elkins, who was strong, funny, and not particularly bright, not unlike Sailor Steve Costigan.

Howard’s life came to a tragic end when he was only thirty years old. In 1936, apparently distraught over his mother’s failing health, Howard walked to his car, sat down, and shot himself in the head. He left a brief suicide note in his typewriter, two lines from English poet Viola Garvin:

All fled, all done, so lift me on the pyre;

The feast is over and the lamps expire.

Robert E. Howard carved out a living as a full-time writer for seven years, an impressive feat at any time, and he managed it during the Great Depression no less. He packed more writing into that brief span than many authors manage over the course of decades. Widely read in his lifetime, Howard’s prominence has waxed and waned in the decades since, as devotees collect rare editions and scholars debate the merits of his work. But while Robert E. Howard may be forever remembered for Conan the Barbarian, boxing fans would do well to also remember Conan’s precursor, the heavyweight champion of The Sea Girl, Sailor Steve Costigan, that fictional fighter “well known in all ports as a tough man with the gloves, and the terror of all first mates and buckos afloat.” –Andrew Rihn