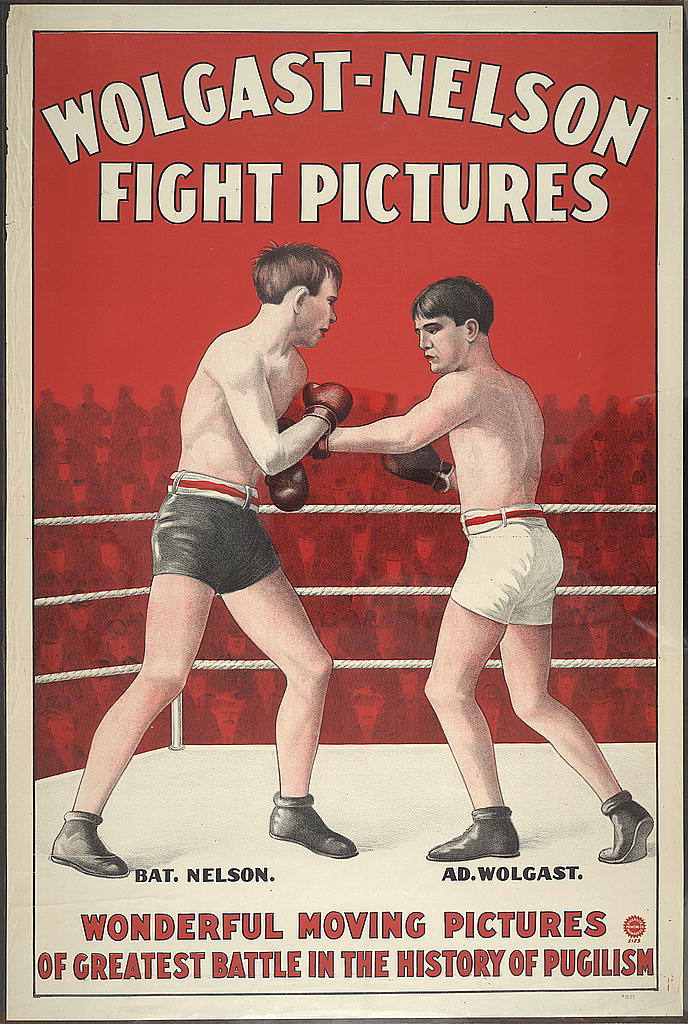

Feb. 22, 1910: Nelson vs Wolgast II

There have been few brawlers whose willingness to do whatever it took to win matched that of Oscar Nelson or Adolphus Wolgast. The careers of both Hall of Fame warriors consisted of one torturous marathon fight after another. Individually, their nigh-superhuman displays of endurance were responsible for herculean dramas that astonished fans. That these two bloodthirsty champions inhabited the lightweight division at the same time was either a godsend or a curse, depending on how much of a stomach one had for prehistoric savagery. Whenever a prizefight had the billing of Nelson vs Wolgast, a scene of inhuman mayhem was virtually inevitable.

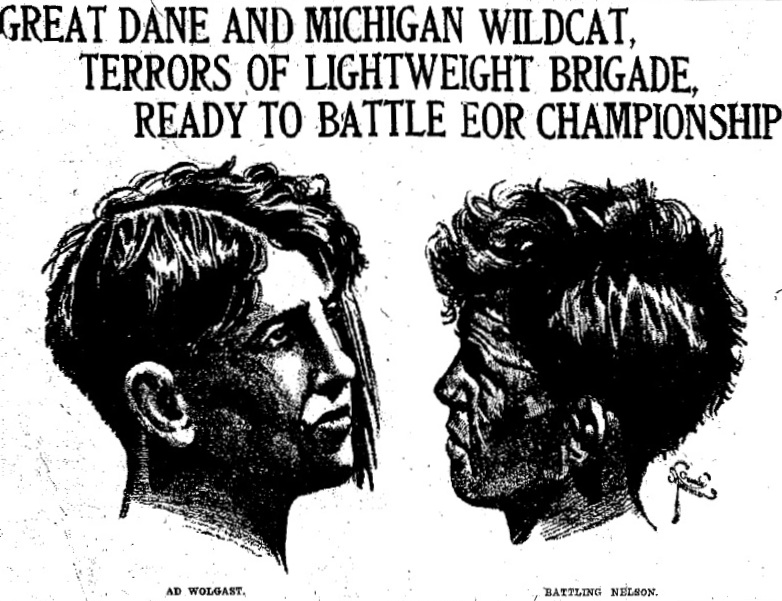

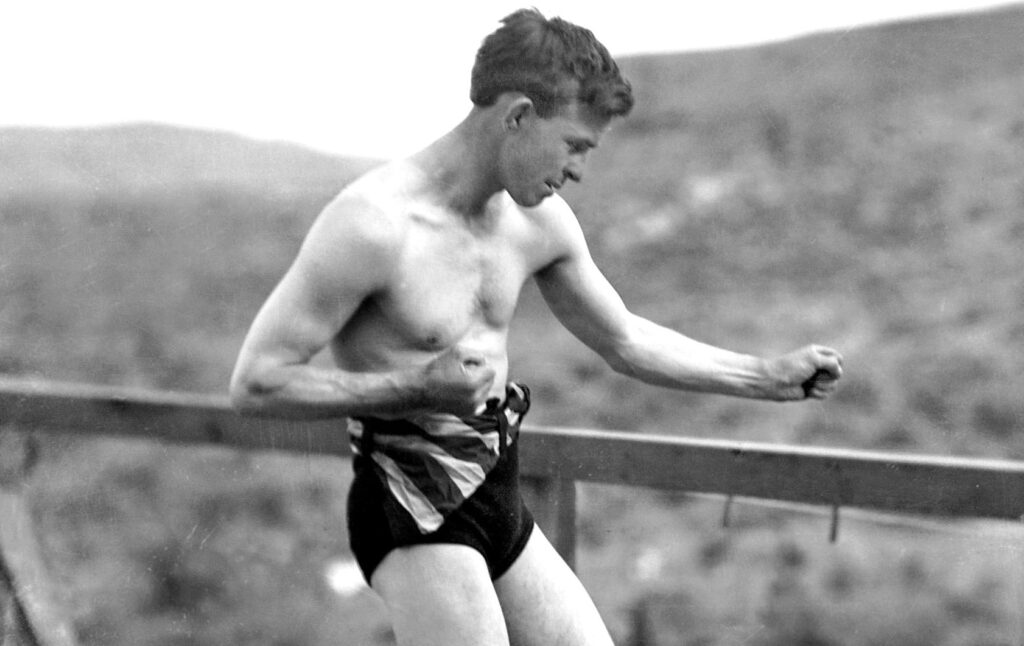

Born Oscar Nielsen in Copenhagen, Denmark in 1882, Nelson moved with his parents to Chicago, Illinois when very young and it was there that he first stepped through the ropes. He turned pro at 14 and by his early twenties had built a national reputation as “Battling Nelson,” one of the dirtiest and toughest customers boxing had ever known. The papers called him “The Durable Dane” and in one 1904 bout, legend has it, an opponent hit him so hard that he did a somersault, yet Nelson still fought on to win. He once won a fifteen round fight despite a broken arm. A merciless body puncher, his favorite target was the liver. A conspicuous cauliflower right ear testified to the hard wars he had seen over the years.

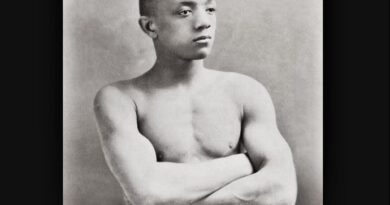

Nelson lost a hard-fought title challenge against Jimmy Britt in December 1904, but rebounded with a knockout in the rematch nine months later to secure the world championship. In a 1906 mega-promotion that drew a then-astonishing $100,000 gate, Nelson accepted a challenge from the ultra-skilled ex-champ Joe Gans. In a fight to the finish, Nelson rose from multiple knockdowns and eventually lost by disqualification in the forty-second round after nearly three hours of fighting under the Nevada sun. Again showing his resilience, Nelson got revenge in two more thrilling bouts with Gans, winning both by knockout to become a two-time world champ.

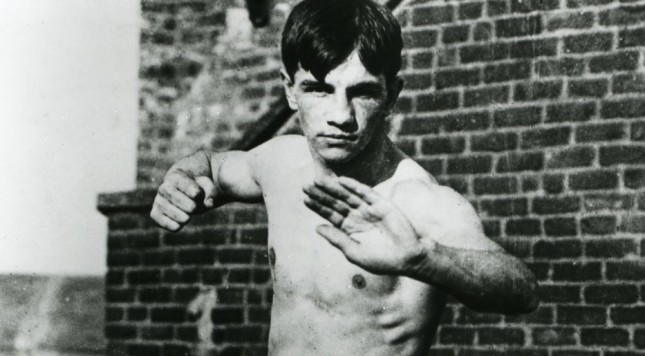

It seemed there was no man alive who could go tooth-and-nail with the ruthless Battling Nelson until Michigan’s Ad Wolgast emerged as a top featherweight contender while plying his trade in the talent-rich rings of California. He was five years younger and, at just under 5’5″, three inches shorter than Nelson. Otherwise, Nelson must have felt he was looking in a mirror when they met. Wolgast’s bravery and aggression seemed limitless as he tore into opponents with a fury the press could only compare with the champion and which inspired the moniker “The Michigan Wildcat.”

By the summer of 1909, 21-year-old Nelson had a record of 40–1–8, with 17 knockouts. He had also fought seven bouts in jurisdictions where official decisions were illegal and not rendered, including bouts against future Hall of Famers Owen Moran and Abe Attell. The sportswriters felt that he had lost to Moran but drew with Attell, who was the reigning featherweight champion at the time.

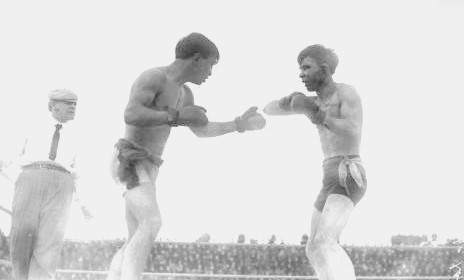

Naturally a featherweight, Wolgast added on a few pounds to challenge Nelson for the 135 pound title at the Naud Junction Pavilion in Los Angeles in 1909. This first encounter was scheduled for ten rounds, and since decisions were illegal in California, Ad could only win the title by knockout. It was the immovable object meeting the unstoppable force, neither man giving an inch. Wolgast, “beat the title holder, Bat Nelson, in ten rounds of as fierce a battle as any fight bug has seen in this city for months,” declared The Los Angeles Times, as both it and The Herald saw Wolgast the clear victor, but he could neither put the champion down nor knock him out, and a bloodied Nelson left the ring still holding the championship belt.

Obviously, a rematch was in order. Promoters in various cities vied for the fight and the rumored site of the match moved from Los Angeles to San Francisco to Alameda and finally to Richmond, California, which was conveniently close to both San Francisco and Alameda. Nelson’s title would once more be on the line, and this time the fighters would have forty-five scheduled rounds to try and secure the knockout. Some fifteen thousand attended the showdown, reportedly paying $37,750 to do so.

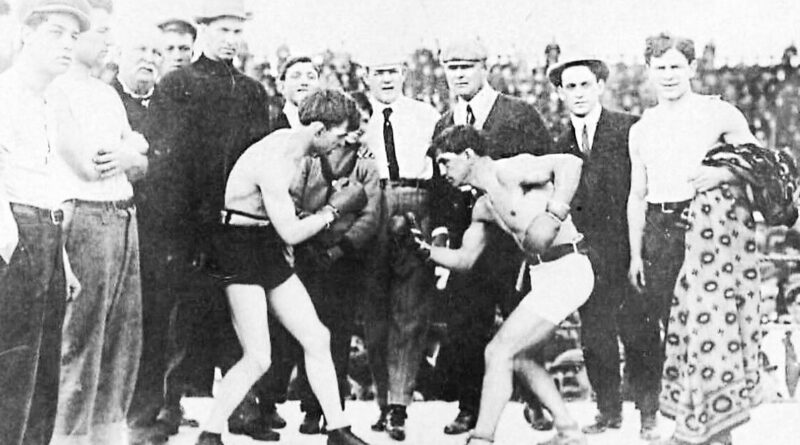

The champion kept his challenger waiting in the ring for fifteen minutes before he made his appearance. According to Alexander Johnston’s 1927 book Ten-and Out!, both despised the other after their first encounter, and “they glared at each other like two wildcats” from across the ring at the start of the rematch. In truth, Wolgast was in a jovial mood, cracking jokes with his cornermen. Johnston said that both men had agreed with the referee Eddie Smith that neither fighter could be penalized or disqualified for fouling in the match.

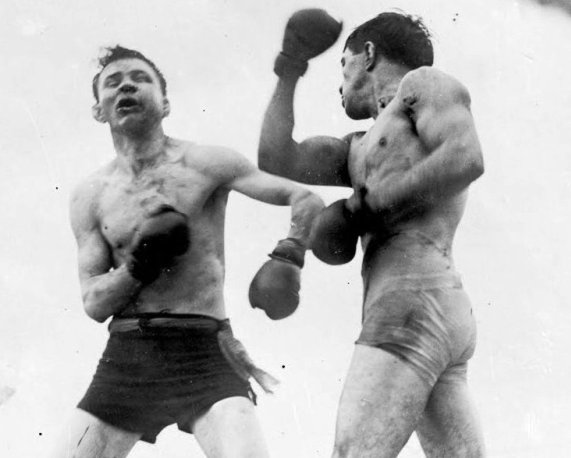

From the beginning, it was clear that Wolgast was adopting a cautious approach to the long fight, something his manager Tom Jones had advised. Despite being the noticeably shorter man, he focussed on jabs and combinations from the outside while the champion waded in with hooks to both the head and body, occasionally driving Wolgast to the ropes in the early rounds. In round two, Wolgast’s jabs drew first blood from Nelson’s mouth. Nelson returned the favor a round later, pounding blood out of Wolgast’s nose. Just before the bell ended round four, the challenger badly hurt the champion with a right to the gut, literally turning his body with the shot. By round five, the hard fighting turned dirty as the men exchanged repeated headbutts. “If he butts, I’ll butt,” Nelson shouted at the ref. “You’re both butting,” a frustrated Smith snapped back.

After five rounds, The Alameda Evening Times-Star had the fight even, with one round for Nelson, one for Wolgast, and three drawn rounds, and by the sixth, the torrid pace had both men already showing signs of fatigue. Nelson’s mouth hung open as he desperately sucked air, but he continued to deliver as good as he received. In the middle of round nine, two of his left hooks to the head staggered the challenger and dominated the rest of that frame. By the end of round ten, blood cascaded from Wolgast’s cauliflower ear, but The Times-Star had him up four rounds to two, with the rest even.

Despite the fatigue of both men, “More damage was done in the last thirty seconds of [round eleven] than during the entire ten rounds preceding,” with Wolgast badly battering Nelson. Rounds eleven and twelve both descended into butting contests. At one point, Nelson is said to have turned to Smith and shouted, “Don’t we have any rules at all?”

By now, Wolgast was ignoring his manager’s pleas to fight on the outside, and both men tore into each other “like tigers” in round twelve. Nelson’s face was grotesque, already looking worse than it had after forty-five rounds with Joe Gans years earlier. A head butt from him angered the crowd in round sixteen, and referee Eddie Smith warned Wolgast for butting twice in round eighteen. Nelson remained the aggressor in the fight, but his features were unrecognizable, and Wolgast seemed to be taking control. After round twenty, The Times-Star had it seven rounds for Wolgast, four for Nelson, and the rest even.

Just when it seemed Nelson was completely gassed, he staggered the challenger with a hard right in round twenty-two, then crowded him to the ropes and got home another right to the chin that dropped Wolgast “as if he had been hit with an axe.” Nelson waved confidently to his corner to signal he knew the fight was over. Then he turned around and was astonished to see Wolgast somehow rising to his feet.

Wisely covering up, Wolgast resumed his original evasive tactics, frustrating Nelson, who desperately tried for the knockout. The fighters had placed a side wager before the match, Nelson betting he could knock his challenger out by round twenty-five. He pushed hard to win the money in that frame, but Wolgast was in full retreat, focused on winning the bet for himself, which he did. In fact, it was Ad who staggered the champion with three successive rights in the middle of the round. The fans who had also bet on Wolgast to last the twenty-five rounds howled with delight as the bell tolled to end the round.

As the battle wore on, no one could blame the fighters for the occasional lull in the action, and both men began missing more often. Nelson attempted a taunting smile in round twenty-six, but all it showed was the bloody mess his mouth had become. Besides, of the two, Wolgast was now obviously the more active fighter. After thirty rounds, the paper had scored fourteen rounds for Wolgast, six for Nelson, and ten drawn rounds.

When he returned to his corner after round thirty, Nelson was told to switch tactics and back off of his challenger. “The Durable Dane” did nothing of the sort, and both men fought the next round mostly on the inside, Wolgast landing an illegal backhand blow in the mix. By the thirty-first round, some felt Nelson had seen enough and cries of “Stop it!” were cascading down from the stands.

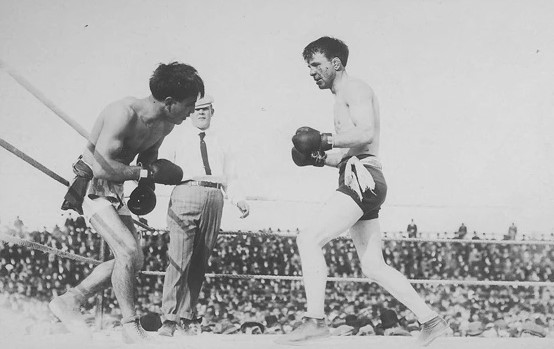

The rounds ticked by and the fighters now frequently fell into clinches. Wolgast still came up with the occasional combination, while an exhausted and mangled Nelson was mostly missing. Toward the end of the thirty-fourth round, Nelson did the unthinkable: he took his first backward step under a Wolgast attack. To the writer for The San Francisco Examiner, he now looked “dead on his feet” and by the end of round thirty-five his face, shoulders, and chest were smeared with his own blood, while Wolgast looked still sharp as he boxed on the outside against his aging, bloodied foe, who slowly plodded after him.

In round thirty-nine, Wolgast could smell victory imminent. Unleashing everything he could muster from his fatigued arms, he sent the champion reeling from pillar to post. Despite three solid minutes of pounding to his head, Nelson refused to go down. After he wobbled to his corner, referee Smith pleaded with him to quit. “No,” replied the proud champion, “I’ll fight it out.”

Legend has it that, at the start of round forty, Battling Nelson was so badly blinded by his own gore that he rose from his stool, accidentally got turned around, and faced the wrong direction, having no idea where his opponent was, and this forced the referee to stop the action. This is not true. The ringside accounts say that Nelson came straight at Wolgast during the round, but received such terrible punishment that Smith was forced to stop the fight. As “The Michigan Wildcat” teed off on him, Nelson’s hands hung helplessly at his sides. When Smith intervened, Nelson tried to fight on and did not relent in going after Wolgast until the police forced him.

“The fallen champion was a pitiable spectacle, wrote The Times-Star. “His face was pummeled beyond recognition. His nose was horribly cut. The left side of his face resembled a huge boil. His cauliflower ear was cut into ribbons and his mouth was swollen to the size of a calf’s liver.” By comparison, Wolgast was relatively unmarked, aside from some minor swelling and scrapes, but he had endured head-butts, a knockdown, and two-and-a-half hours of brutal fighting with a relentless champion.

“I fought a careful battle,” Wolgast told the paper afterward. Only a battle-hardened slugger like him would call what just occurred ‘careful.’ “I was fresh at the finish and could have fought many more rounds,” he continued.

Nelson, too, said he could have continued on for the forty-five-round distance had he been allowed. “Wolgast’s blows were not hurting me,” he insisted. But referee Smith explained his reasoning to reporters, saying, “I did not want to take any chances, as there might have been a tragedy if the fight had gone further.” Smith said the great Nelson was clearly beyond his prime, and he was. He never again fought for a championship but remained in boxing for seven more years before finally hanging up the gloves.

Ad Wolgast was an exciting new champion, but his brutal fighting style and the frequency with which he fought burned him out quickly. He defended his belt seven times in less than three years before losing it in the second of two classic slugfests with Willie Ritchie. Down on the floor from a hard right, Wolgast reached up to land two low blows straight into Ritchie’s groin, forcing the ref to award the fight to the challenger. By twenty-five years of age, Ad Wolgast was already washed up; he just didn’t know it. He fought on until 1920, by which time he was already a physical and mental wreck.

Nelson and Wolgast fought for a third time in 1913, a no-decision bout in Milwaukee. The papers said Wolgast won, but it mattered little. Both men were badly faded and both would die pitied and penniless, Nelson in 1954 and Wolgast a year later. Wolgast in particular was a sad victim of the sport, spending the last three decades of his life suffering from dementia, and what we now recognize as CTE, his condition incurred from years of toil and punishment in his brutal profession. –Kenneth Bridgham