The Champion Writer

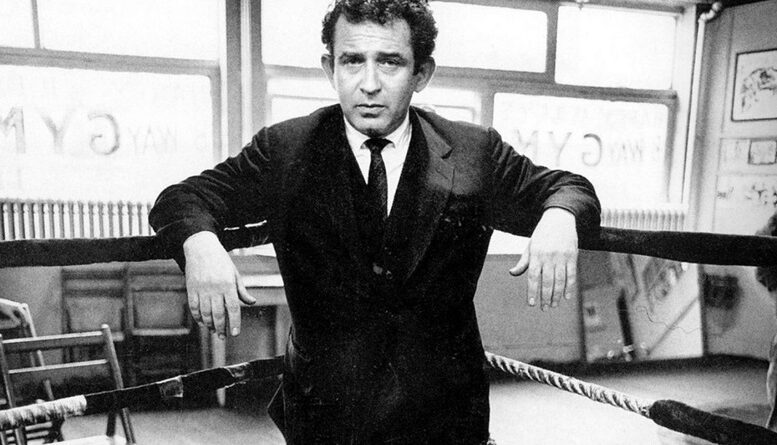

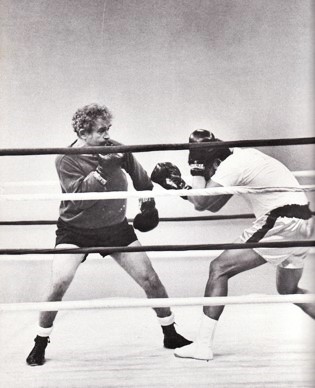

It’s been over a century since the birth of the novelist, public intellectual, part-time pugilist and full-time pundit the world knew as Norman Mailer. A towering figure in American post-war letters, Mailer wrote numerous best-selling novels, won the Pulitzer prize twice, and helped found The Village Voice. Chuck Klosterman, who never met him, called Mailer “a deeply fascinating, impossibly singular, sporadically terrifying personality.” James Baldwin, who knew Mailer well, described him as “confident, boastful, exuberant, and loving, striding through the Paris nights like a gladiator.” Mailer was part of a literary lineage extending from Byron and Hemingway: the author as would-be pugilist. Few writers have had their public personas so intrinsically linked to the sport of boxing as Norman Mailer. And fewer still have worked as tirelessly as he did to nurture that link.

Boxing meshed perfectly with Mailer’s view of the world. He regarded every intellectual engagement as a contest where the participants would emerge as either triumphant winner or embarrassed loser, as he sought to prove himself the most masculine, the strongest, the greatest — in short, The Champ. “Boxing obsessed him,” wrote The New York Times after his death in 2007, “and inspired some of his best writing. Any time he met a critic or a reviewer, even a friendly one, he would put up his fists and drop into a crouch.”

Indeed, Mailer consciously and publicly identified himself and his writing, both of which he took quite seriously, in pugilistic terms. Near the end of his life, he released The Spooky Art, a collection of his thoughts on the writing life, and it is littered with references to boxing. Studying writing in college courses was like fighting in the amateurs: “Being a young writer in such a course can bruise the psyche as much as being a novice in the Golden Gloves can hurt your head.” Bad reviews felt like getting knocked out: “It’s the way a young prizefighter with a promising start can get knocked out early in his career and come back to have a good record. The time he was knocked out has become part of his strength.” He equated the toll writing a novel takes on the writer with the toll a fighter’s body takes. “I think often of the aging boxer who has to get in shape for one more fight and knows the punishment it will wreak on his body. That’s also true in my profession.” And the risks, too, were equal in his eyes: “Just as a fighter has to feel that he possesses the right to do physical damage to another man, so a writer has to be ready to take chances with his readers’ lives.”

Mailer never delivered the great American boxing novel, if such a thing should exist. Like Hemingway, he occasionally fitted a character with a boxing background in his novels, but for this reader it’s his boxing nonfiction that interests more. He wrote about the sport only sporadically, but when he did, he spilled forth on the subject in a rush of language that revealed his awe for the spectacle and his respect for the fighters, not to mention his fascination for the male ego and masculinity, themes he spent his entire life exploring.

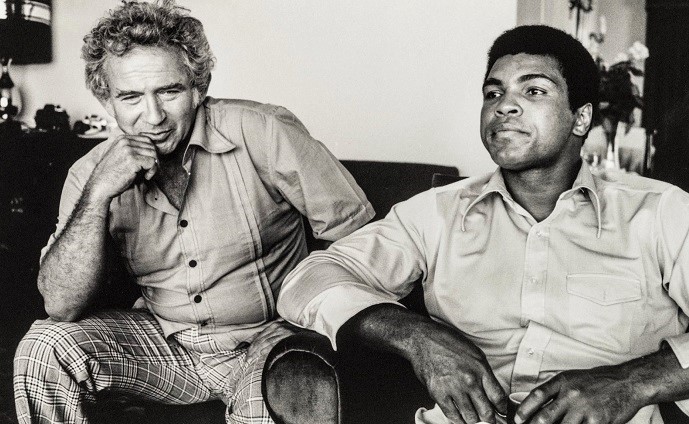

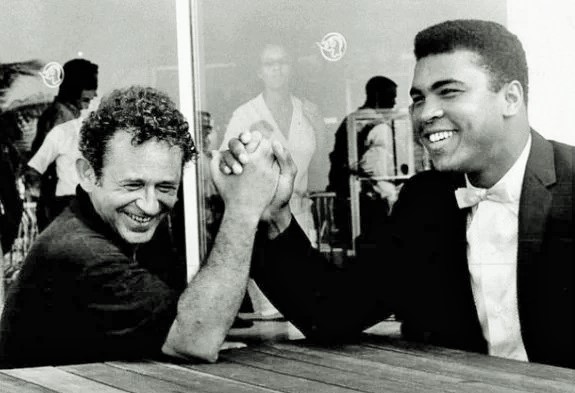

Mailer is most identified with Muhammad Ali. In 1971, he wrote an article titled simply “Ego” for Life magazine, ostensibly centered on “the superfight of the century,” Ali vs Frazier I. Published just eleven days after that monumental battle, it featured a cover photo taken by the Chairman of the Board himself, Frank Sinatra. It is a sprawling, dizzying essay, bursting with all the clarity and acumen Mailer could rally, and it would later be republished as a short book titled King of the Hill. But Mailer’s fascination with Ali extended beyond boxing. In Ali, Mailer found a willing vehicle with which to discourse on subjects such as race, counterculture and ego. By 1971 and that titanic first Ali vs Frazier clash, it was clear to many that “The Greatest” was a once-in-a-generation figure and Mailer crowned him “America’s Greatest Ego,” perhaps what the writer himself aspired to be.

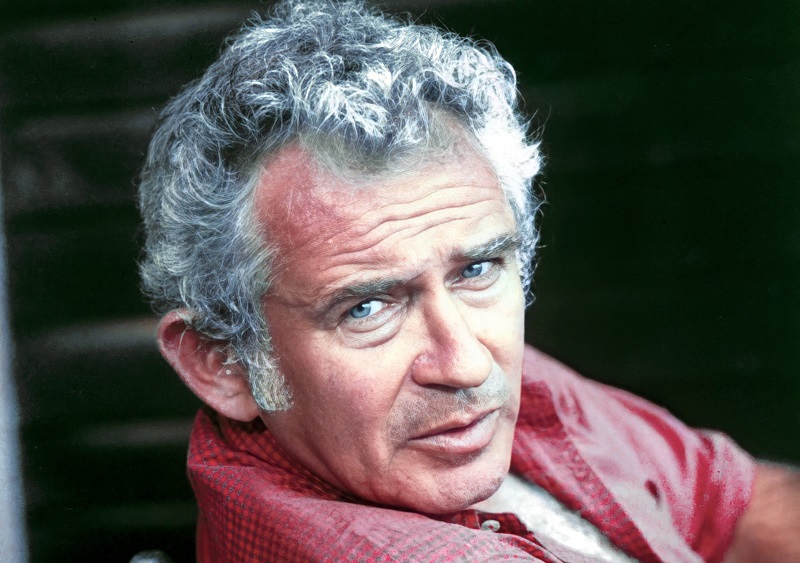

After his passing in 2007, obituaries crystallized this facet of Mailer’s demeanor. “Towering Writing with Matching Ego,” wrote The New York Times. “Ego with an Insecure Streak,” declared The Los Angeles Times, describing Mailer as “a major talent who could not keep himself from reminding you that he was a major talent.” Compare that to how Mailer himself described Ali: “like a six-foot parrot, he keeps screaming at you that he is the center of the stage,” and tell me that he did not recognize that part of himself within his obsession with Muhammad Ali.

In 1975 Mailer revisited Muhammad Ali, and his ego, this time with a book-length essay on Ali’s challenge of George Foreman the year before, titled simply The Fight, the volume taking its title, and some of its structure, from an expansive nineteenth century essay by William Hazlitt. Mailer himself appears in the book, describing himself in the third person, a literary technique known as illeism. We follow ‘Norman’ from Ali’s camp in Deer Lake, Pennsylvania to Kinshasa, walking alongside one of the great writers as he observes the lead-up to a truly great fight. This was a technique Mailer had used before, its effectiveness a point of debate among critics. In The Fight, Mailer added a layer of African mysticism to his philosophizing on boxing and ego as Kinshasa, and its residents’ chants of Ali bomaye!, evidently impressed the author.

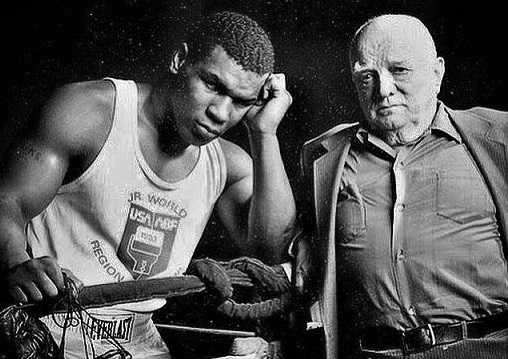

As a result of these two nonfiction works, the standard view on Mailer connects him most closely with Ali, but this overlooks the importance of another boxing figure on Mailer. After all, in addition to Ali, he also wrote about Floyd Patterson, José Torres, and Mike Tyson, and their common denominator is readily apparent to boxing aficionados; all three were trained by the same man, Cus D’Amato. If Mailer aspired to the boisterousness and irrepressible ego of “The Louisville Lip,” perhaps he also recognized himself, if hesitantly, in the cantankerous and ascetic trainer.

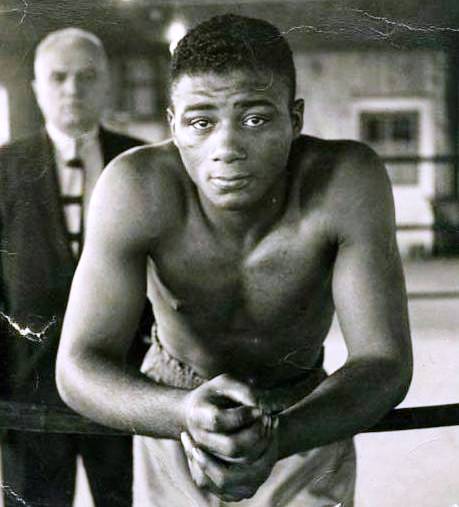

Mailer first wrote about D’Amato when he covered the 1963 rematch between Sonny Liston and Floyd Patterson for Esquire. What Mailer produced was a groundbreaking piece of journalism that confirmed his role in establishing what would become known as ‘New Journalism,’ the essay “Ten Thousand Words a Minute” reading in part like a manifesto decrying the tyranny of what Mailer viewed as mediocre prose, while advocating the role of the novelist as writer par excellence. “An old fight reporter is a sad sight,” writes Mailer, “he looks like an old prizefight manager, which is to say, he looks like an old cigar butt.” Somewhere in this disquisition on belles lettres, Mailer found space to convey Liston, Patterson, and Cus as fully-formed characters, and in letters to Esquire the following month, readers raved about Mailer’s effort, one declaring that “he does for [boxing] what the motion picture Shane did for the Old West. It is as though you have never really seen it before; it is entirely fresh and jolting.”

At the time D’Amato was a little known figure to the boxing public, let alone mainstream sports fans, but Mailer is effusive in his praise and devotes plenty of copy to the man, declaring that “D’Amato was one of the bravest men in America. He was a fanatic about boxing, and cared little about money.” Mailer continues: “He hated the Mob. He stood up to them. A prizefight manager running a small gym with broken mirrors on East Fourteenth Street does not usually stand up to the Mob, any more than a chambermaid would tell the Duchess of Windsor to wipe her shoes before she enters her suite at the Waldorf.” Mailer’s infatuation with the mystique of a reclusive and iron-willed yet unrecognized genius is clear. How else to explain a passage like this: “As a talker, Cus D’Amato was one of the world’s great weight lifters, not brilliant, but powerful, nonstop, and very solid. Talk was muscle. If you wanted to interrupt, you had to bend his arm off.”

A quarter of a century after writing about Patterson vs Liston, and after devoting much of the 1970’s to his studies of Muhammad Ali, Mailer wrote about another champion: Mike Tyson, that lightning-rod of a heavyweight no one could ignore during the 1980s, this time for Spin magazine in 1988. Mailer was in Atlantic City covering the Tyson vs Michael Spinks unification clash, a 91 second blowout which saw “Kid Dynamite” emerge as the undisputed world heavyweight champion. Mailer holds that at that point in 1988, there was no active heavyweight who could beat Tyson. This sends him into an extended report on the training and preparation that makes “the baddest man on the planet” so very bad, the perfect invitation to espouse the philosophies and triumphs of Tyson’s former trainer, Cus D’Amato, then already three years deceased. Described as a “father, high priest, and the spirit of even-handed justice,” the shadow of D’Amato allows Mailer to resuscitate his own aging existential quandaries through the language of the ring. Deception. Ego. Fear. Making your own stubborn stand against the inevitable passage of time and the atrophying of one’s cultural import.

As with Ali, Mailer must have seen in D’Amato an aspirational figure, an idealized version of himself. Or more accurately, an idealized version of a part of himself. In public, Mailer was known to be boisterous and outgoing, and antagonistic to those he saw as intellectual or professional rivals. But privately, he was also a hermitted author, holed away in his tiny office writing for eight to ten hours a day. Mailer’s ego was split, unreconciled. What he must have seen in both Ali and D’Amato were men who knew who they were. They had their ideals and their philosophies and they lived those values completely. Not to say they didn’t struggle, as we all do, alone in those sleepless hours before dawn when anxious thoughts dominate, when we ponder the mess we’ve made of this life and think of the dreams we’ve stopped chasing. Of course D’Amato and Ali lived as mortal men, but in the writing Mailer could construct the kind of men he most admired, most envied, and, most begrudgingly, could never wholly be.

Mailer fashioned himself in some respects as the heir-apparent to Ernest Hemingway, the most masculine of authors. Boxing, for both, was a way to prove their macho credentials, to distance themselves from any image of the effete intellectual. And so it was inevitable that Mailer, who had included himself (in the third person) in so many articles and books, would cast himself as the central character in a boxing article. “The Best Move Lies Very Close to the Worst,” written for Esquire, thirty years after his groundbreaking Liston vs Patterson essay appeared there, is also my favorite. Appearing as number three in the magazine’s list of “Sixty Things Every Man Should Know,” an older, slightly nostalgic Mailer is given the liberty to delve into reminiscence. He describes his time spent in New York’s famous Gramercy boxing gym, now eschewing the philosophies of other men in favor of his own experience. He relates the lessons learned in the ring with an endearing amount of humour, often self-deprecating, and humility. His ego is placated, however, through a number of humble-brags about meeting Sylvester Stallone, and sparring with both former world champ José Torres and Hollywood heartthrob Ryan O’Neal. And so, in just five pieces of nonfiction, Norman Mailer forever cemented his place within the annals of boxing literature, placing himself on a list that includes Homer, Jack London, Bud Schulberg, and so many others.

Near the end of his life, Mailer characterized the theme of his work as “the relation between courage and brutality.” To a great extent, boxing structured the way Mailer thought, or at least it provided a language for Mailer to express his favored themes of conflict, violence, and bravery. Of course, his influence on boxing was much less consequential than boxing’s influence on Mailer, as he was a keen observer of a sport that has never been lacking for keen observers. He wrote about Patterson and Ali, José Torres and Mike Tyson, all figures that without Mailer would still be famous. His observations of the sport are excellent but ultimately nonessential. In this way he lived up to the measure of Hemingway. Perhaps he surpassed it. Boxing provided a lifelong passion for Norman Mailer and that passion is linked inextricably to the persona he created. He wanted to be the Muhammad Ali of the literary world, an undeniable champion who aroused hate and love in equal parts. But he also lived as the literary Cus D’Amato, cloistered away in his opposition to the prevailing winds of power. In Mailer we see an ego in conflict, and I suspect he would have been okay with that. –Andrew Rihn