Golden Gloves

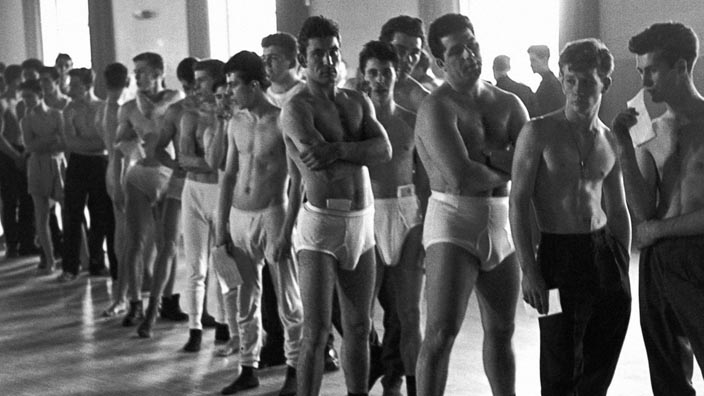

In grainy black and white, half-naked boys and young men form a line in a Montreal gymnasium. They’re lean and fit, registration cards tucked into snug white briefs pulled up to their navels. Some of them pose for the camera. Sunlight streams through windows onto others who stare off at something, their shadows drawn to the focal point. Do they see a way out?

The camera winds through the line of youths. Young men scowl while boys look scared; all the while the vapid voice of a male narrator intones:

[w]hereas you accept my registration, I, the undersigned, do hereby forgo, both for myself and my heirs or executors of my will, all grounds that I may have for complaint against the organizers … pertaining to any accident to which I may fall victim on the occasion of this championship … In consideration whereof, witness my signature.

On “signature” the scene fades out by boring into the forehead of one of the youngest at the end of the line, where his brain may soon be pummelled into a void. The narrator sounds bored as bare-faced boys brush by like chicks on a conveyor belt.

Now we’re in another gymnasium, this one larger and darker, as if inside the skull of the boy at the end of the line. The fretful chord of an electric guitar echoes as a spotlight shines on a trainer watching three fighters shadow-box in the middle of the gym. Then one of them punches at the camera just as guitars and drums erupt. Translated below from the French, a male voice howls:

Joe, Joe, Joe, he’s very well-trained,

He wants to be champion of the world;

Joe, Joe, Joe, he really likes his work,

But what he likes most is to see his opponent flat on the mat.

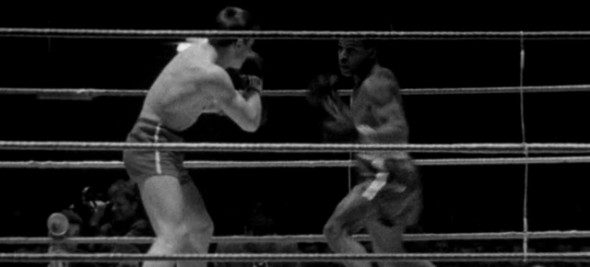

The fighters variously skip rope, hit the punching bag, do jumping knee-lifts or bob their heads up and down, all in synchrony with the tune’s jubilant rhythm. Suddenly the song stops mid-stream and we cut to a boy lying flat on his back. The shot zooms out and we see he’s just stretching on a towel. He gets up and the four leave the gym, their footsteps dissolving as we cut to a close-up of the spotlight, which fades to black: like the others in line Joe wants to be champion of the world, but instead his ‘light’ is snuffed out.

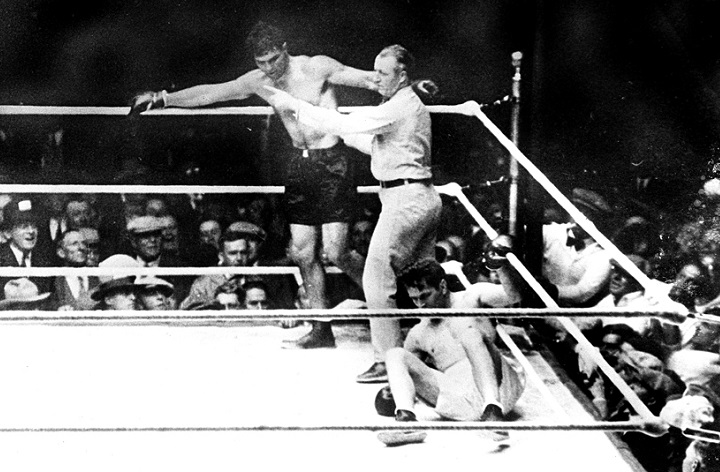

With such deliberate choreography and editing, Golden Gloves (1961) asks what it means to win at a sport designed for society’s losers. Boys of poor families imagine amateur boxing is a way out of poverty and into the professional ring where a million-dollar purse awaits.

We follow two Montreal fighters training for a Golden Gloves championship. Ronald Jones, 20, baby-faced and black, lives in a tenement house with his younger brother and sister and his mother. For his breakfast she cracks an egg into a pan of sizzling bacon and grease. A piece of eggshell falls in and she tries repeatedly to pull it out, but fails.

She serves Ronald the eggs and bacon. He grins and coos. Moving as it is to see how much mother and son love each other, he’s going to swallow eggshell. I’m made to wonder if her boy ends up a shell of a man, cracked and fried by the trials of the boxing world.

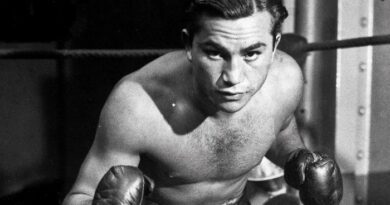

Meantime Georges Thibault, 26, flat-faced and white, is a waiter in a seedy men-only taverne, a sort of sty or coop filled with “his friends, his supporters, his admirers.” Toothless and beak-nosed, they swill beer as cigarette smoke licks their greasy pompadours.

Georges explains how he got his start in amateur boxing: “So I put the gloves on, see, and there’s this heavyweight … a fireman. He was on fire after I’d finished with him, you bet.” His friends grunt their assent, then perform “Operation Hot Seat,” setting fire to a piece of paper slipped under the bum of a drunk dozing in a chair. He jumps up and squeals; they dump beer on his head and cackle.

Golden Gloves captures a bevy of details about Montreal’s amateur boxing environment in the early 60s. The film judges neither the brutality of boxing nor a society that goads poor youths into wasting each other in the ring. Instead, through a sequence of orchestrated images, I’m invited to look back fifty years and wonder how little has changed. —Marko Sijan

My son, Christian King Colunga, is currently competing in the Chicago Golden Gloves. Watch out for him. Next lightweight champ will be out of Melrose Park, Illinois.

My grandfather, Tommy Dalton, was very involved in the boxing scene in Montreal. He competed and then was a referee, eventually being inducted into the Canadian Boxing Hall of Fame in 1976…shortly before he died. Thank you for shining a light on this important piece of Montreal history.