Righting A Wrong: The Story Of Homicide Hank

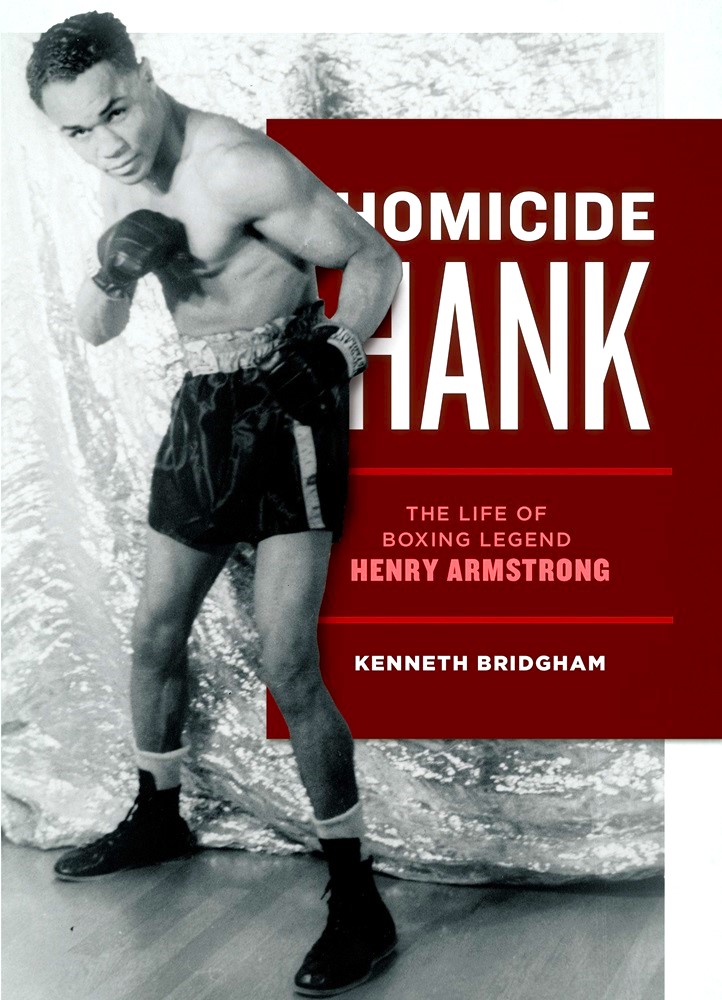

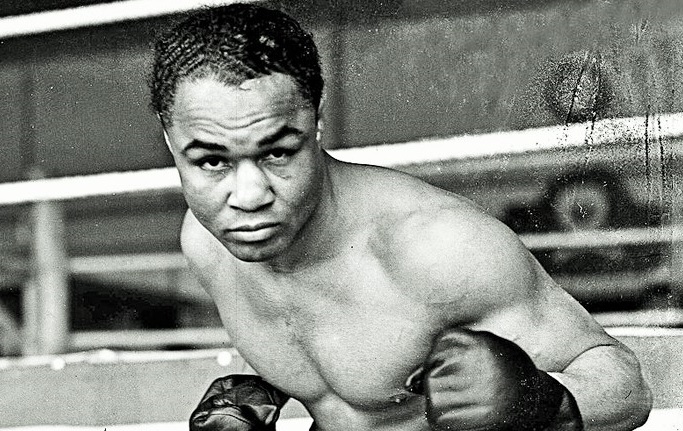

Author and site contributor Kenneth Bridgham has recently published his second book, a biography of one Henry Melody Jackson Jr., aka the great Henry Armstrong. Set in an America beset by racism, corruption, the Great Depression, and World War II, Homicide Hank: The Life of Boxing Legend Henry Armstrong chronicles the story of a true ring great, from his humble beginnings to the heights of stardom and on to his post-boxing years as a man of God. Surprisingly, it is the only complete biography of one of pugilism’s most significant champions and thus deserves to be widely read and discussed. Moreover, its publication is the perfect opportunity to learn more about its ambitious author who is quickly becoming a renowned authority on American boxing history. Check it out:

Your first book was about the life and times of bare knuckle champion John Morrissey, but your newest work centers on Henry Armstrong, the great triple-crown champ, which means a completely different social context, and almost a different sport considering how much boxing changed in the span between Morrissey’s day and when Armstrong was active in the 1930’s. What compelled you to shift your focus to “Homicide Hank”?

When I initially began work on the Morrissey book, I knew vaguely of this interesting character from the sport’s history and wanted to learn more about him. I was surprised to find that no scholarly book-length biography had been written on Morrissey, at least as of the time I began my research. That project began as an article I hoped to get published somewhere, but as I found more and more information, it gradually became book length. But as I was completing the Morrissey book, I was thinking about what my next project would be. There were three specific people I had in mind, and I settled on Henry Armstrong. The first reason was that I had asked myself, “Who is the best fighter to never have a biography written about them?” Other than an autobiography long out of print, that was Henry Armstrong, an astonishing fact, considering how highly regarded he is by those who know the sport. The secondary reasons were that he was a more sympathetic character and more easily researched than the two other boxers I was considering. But again, it’s almost hard to believe, not to mention an injustice, that up until now there has never been a proper biography on such an important fighter.

Well, now there is, thanks to you. One might say you are righting a wrong, pun intended.

Regarding the differences between boxing in Morrissey’s time and Armstrong’s, there are still some important links that connect them. First, boxing, regardless of the era, was always a sport of the oppressed. Both Morrissey and Armstrong achieved what they did by rising above poverty and discrimination to represent an oppressed people. In the cases of both biographies, this allowed me to construct the narratives around a rags-to-riches story set against a backdrop of historical and social context. Secondly, a boxing match is a narrative unto itself. Whether it is a gloved first round knockout in the 20th century or a marathon bare-knuckle war of attrition in the 19th, a fight almost always has an introduction, rising action, climax, and falling action. The inherent drama of a boxing match was available to me, whomever I was writing about, regardless of the period.

So I take it that it was your interest in boxing that eventually drew you to Morrissey and the bare-knuckle era, and not the other way around. Is it the same for your enthusiasm for Pittsburgh pugilists? Or, let’s go back a bit: how did you first get interested in the history of prizefighting?

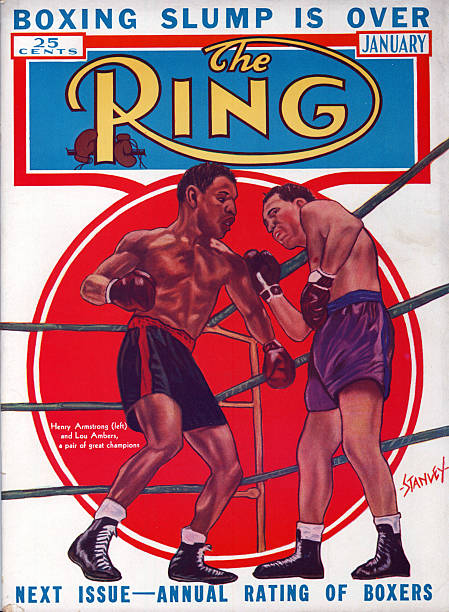

I had a passing interest in boxing from the first time I saw Rocky as a child. I remember jumping around my living room, throwing punches during the final fight. But I only got into watching real boxing when I was in my 20s, when I began watching it with friends. Once I discovered some information on the sport’s history online, investigating the great fighters and fights of yesteryear became an obsession, and it didn’t take long to discover the sport’s bare-knuckle past. Growing up near Pittsburgh, my interest in the stories of Pittsburgh’s past as a breeding ground of pugilistic talent was a natural extension. As far as getting into live boxing, that came later, when I was in my early 20s and watching with my friends the major fights and fighters of the late 90’s and onward, De La Hoya, Lewis, Tyson, Jones. Shortly thereafter, I was working at Borders Books & Music and began picking up The Ring magazine. This was in the era of Lewis vs Tyson and De La Hoya vs Vargas. The promotions to those fights and reading about them in The Ring really drew me in and The Ring‘s articles about historic fighters, as well as some websites around the subject, sparked my obsession with the sport’s history. Soon enough, I was buying every new issue of The Ring, KO, and World Boxing. The fact historians could trace back the lineage of champions and the records of boxers into the 19th century amazed me at the time. For Christmas 2002, my dad spent way too much money and bought me nearly every issue of The Ring from about 1930 to 1990, along with some outliers from the other decades. I still enjoy combing through them, and of course they were a great help with writing the Armstrong book.

So a generous father and old copies of The Ring were key inspirations. Any particular books or authors which were also significant?

I think the first boxing book I read was either A Flame of Pure Fire, Roger Kahn’s biography of Jack Dempsey, or the early 2000s edition of A Pictorial History of Boxing by Fleischer and Andre. Those were great ones to start with, and now I have an overflowing boxing bookshelf full of hundreds. Adam Pollack’s books on the heavyweight champions were another game changer for me. How intensely he researches each and every fight from the pre-TV era was mind-blowing and set a new bar for us obsessives. I’ve actually been working up a list of my all-time favorite boxing books, and it keeps getting longer. It’s hard to single one out, but I think I can. It’s short and not as revered as some other books, but Springs Toledo’s Smokestack Lightning about Harry Greb is brilliant. Toledo always does a fantastic job staying with the facts of history but also bringing his subjects to vibrant life. It really feels like you’re part of Greb’s entourage as he speeds through opponents and life. Of course, it helps that I grew up in the Pittsburgh area, so I may be biased.

I got my BA in English from Pitt before I really got hardcore into the sport, so my affinity for writing goes back even further. But yes, ever since I began reading The Ring I always wanted to write about the sport. But earning a real living and life in general got in the way of me really pursuing writing as much as I should have for years. It wasn’t until my son was born in 2011 that I began to slowly put together Morrissey’s story with any intention of publishing anything, and that took me more than eight years to finish. In the past year, I’ve stopped watching live boxing, so my knowledge of current fights, fighters, and issues in the sport isn’t as strong as it once was. That’s why The Fight City, with its strong respect for boxing’s fabulous history, is a good fit for the stuff I write.

How difficult was it to research Armstrong’s life? And were there any surprises along the way?

The main primary sources I used were the old newspaper and magazine articles with first-hand accounts of Henry’s fights. My collection of The Ring issues were a source for this and there were also interviews and articles written by Henry in his later years in several magazines. Fellow boxing historian Clay Moyle was especially helpful with these. He told me that he had once considered doing an Armstrong biography and lost interest in the project. As you probably know, Mr. Moyle has maybe the most extensive collection of boxing books and magazines around, and he still had his old research file on Henry. He was kind enough to send that file to me, and that helped me build a framework for Henry’s life. Armstrong was not afraid to talk about his life and career when interviewed. He was a well-spoken, friendly guy. He liked to talk about his youthful accomplishments, especially if it brought attention to his Henry Armstrong Youth Foundation.

There were three things I found most unexpected in exploring Henry’s life. One was that, even in old age, he never seemed to hold much of a grudge against the men who clearly ripped him off during his career. Multiple interviewers prompted him to open up about the ways guys like Eddie Mead stole tens of thousands of dollars from him during the Depression era, but he clearly didn’t like doing so. Whether this was because he didn’t want to come across to the public as bitter or because he genuinely held no hard feelings is anybody’s guess at this point.

The second surprising thing was an article I found where he admitted that his impressive 46-fight winning streak between 1936 and 1939 may not have been entirely on the level. He openly admitted that at least one win was fixed and that he would not have been surprised to find out that others were as well. Few boxers then or now would admit to that. They might cop to some of their losses being arranged (and Henry did that too), but few admit that their wins were dubious, especially those that are part of a significant piece of their legacy. But then, Henry’s legacy has so many strong points that admitting doubt about one of them can’t harm his standing much.

Speaking of fixes, that leads me to my third surprise. It has long been common talk around Henry’s record that his draw with Ceferino Garcia for a record fourth division championship was a fix. The story goes that Henry should have won it easy and that a shady ref was paid off. Watching the fight film and reading the first-person accounts of people who were there, I’m not entirely sure it was a fix at all. It was definitely a close fight. Yes, many thought Henry deserved the nod, but just as many favored Garcia, and there were those who felt a draw was appropriate. Perhaps most importantly, the referee George Blake was by all accounts a stand-up guy with an impeccable reputation. Henry always asserted the fight was fixed, and maybe it was, but it is not as clear cut as modern commentators and writers would have you believe.

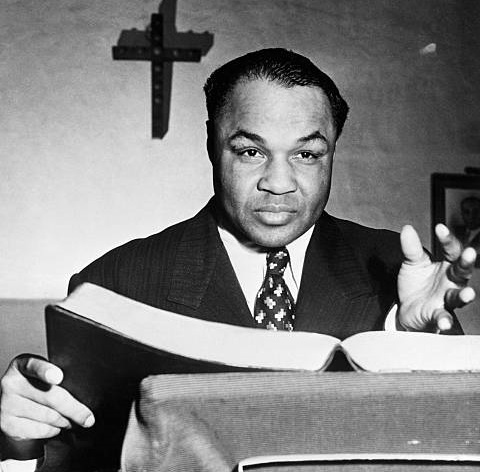

One imagines Armstrong’s Christian faith might be a factor in his attitude towards the people who stole from him, specifically Christ’s commandment to forgive others and “turn the other cheek.” As I understand it, that faith transformed his life.

Henry claimed to have had multiple religious experiences that were direct messages from or visions of God, from childhood into adulthood. Without getting into my personal feelings about religion, I decided to report these incidents as Henry told them and let the reader form their own opinions about the nature of Henry’s faith. When he became a preacher later in life, he was very worried about being perceived as a pretender, a hustler, or a Johnny-come-lately, but religion was a centerpiece of his upbringing, and his mother and grandmother pushed him to become a preacher from the day he was born. He took a different route in his early adult life, but he credited God with awakening him out of his depression and alcoholism once his boxing career was over. When he devoted himself to the Bible and pulpit, he went at it with the same single-minded devotion he had once applied to the ring: all-out. He even called his study of the Bible “training,” like a fighter would his preparations for the ring. And he earned a reputation as a sort of force of nature up there. He was once “Hurricane Henry” but he used that same furious energy to become “God’s Ball of Fire.” So, I’ll leave it up to the reader as to how much of his preaching career was genuine faith and how much was showmanship; but no one can deny that he went at it with dedication and passion.

To my mind, Armstrong is a strong candidate for being at the very top of the list of the all-time greatest boxers, pound-for-pound. What is your take on his standing and was your perception of this altered at all over the course of researching and writing the book?

Well, I separate “greatest” and “best.” When considering the “greatest,” I also consider their historical impact on the sport and their social impact on the country or world. It’s not the only factor I look at, but I account for that along with their abilities, longevity, records, quality of opposition, titles, and records set when determining greatness. Therefore, my top ten greatest are Robinson, Ali, Louis, Armstrong, Pep, Greb, Johnson, Langford, Duran, and Benny Leonard, in that order. That’s part of what led me to write about Henry. I went down my list of greats and asked myself who is the highest ranked not to have a biography about him. Robinson, Ali, and Louis all have many books out about them. There were none in print on Henry, which, again, I found hard to believe.

If we’re talking the “best” fighter ever, in his prime, Armstrong would certainly be in the conversation for the number one spot. I wish there were motion picture footage of Greb in the ring to compare with the existing footage of Armstrong’s stamina and aggression and see who was truly boxing’s greatest brawler. Then, when you get into those mythical matchups, even when film footage exists of both A+ fighters, it’s very difficult to judge who is better, particularly if they were magically made the same size, because all fighters’ styles are built to accommodate their physical dimensions. Armstrong vs Robinson is a good example of this. Even at his best, I don’t think Henry could have beaten Sugar Ray due to Robinson’s sheer size advantage, as well as his other outstanding abilities. But if you made them literally the same dimensions? Who knows what that would even look like.

When I first started the project, I rated Pep at four and Armstrong at five on my greatness ladder, mainly because I looked at Pep’s longer undefeated streak and greater longevity. But researching and writing about Henry’s career convinced me his greatness supersedes Pep’s. His overall quality of opposition was much better than Pep’s, and his cultural impact was enormous. That’s the side of Henry’s boxing legacy that I most hoped to communicate with this book. His winning three-division titles is the first thing anyone ever brings up about him, and that’s a mind-boggling achievement. He was fast and powerful, ridiculously rugged, and frighteningly aggressive at his peak. Like you said, he’s definitely in the conversation when it comes to the all-time best, pound-for-pound. But his real importance was as a rare idol to Black Americans in the Depression era, right alongside Joe Louis. A sociologist who visited a Southern school for Black students in that period noted that the students there didn’t know who the President was, what a president did, or what the U.S. Constitution was, but they all knew who Henry Armstrong was. Why? There are a number of reasons, but certainly one of them was his setting an example of how to rise out of oppression and poverty and fight, both figuratively and literally. As Armstrong once said, “You can’t Jim Crow a left hook.” And he had a hell of a left hook. — Neil Crane