Plaster Of Torrance (Part One)

Last month we marked the anniversary of the legendary and highly controversial, not to mention consequential, first fight between Miguel Cotto and Antonio Margarito. To pay further tribute to this historic clash, we re-feature here Rafael Garcia’s outstanding in-depth examination of the bout and its repercussions, with thanks to the University of Chicago which first published the essay in their excellent collection The Bittersweet Science: Fifteen Writers in the Gym, in the Corner, and at Ringside, edited by Carlo Rotella and Michael Ezra. Check it out:

Plaster of Torrance: Unwrapping the Meaning of Antonio Margarito

“The only sort of relationship worth having with boxing is one of love and hate at the same time.”

“Is that so?”

“It could be all love, or it could be all hate. But neither would give you the whole picture. You’d be missing the forest for the trees and the trees for the forest. People say you don’t want to miss the forest for the trees, but you’ve got to look at the trees too.”

“Okay.”

“When it comes to boxing, all love makes you a savage.”

“What about if you hate it?”

“All hate makes you a pompous ass.”

We were surrounded by Puerto Ricans. Most of them had come from the East Coast, arriving one or two days before fight night. A fifty-something high school teacher and his early thirties nephew were sitting in the row in front of ours. While the older Puerto Rican philosophized, the younger one darted glances at a woman with a painted-on-tight scarlet dress who sat across the aisle. His careful timing guaranteed the woman’s bulked-up male companion was always turned in the opposite direction when he looked at her.

The arena was halfway full with half a fight to go before the main event. My dad served the teacher his cue on a silver platter: “What’s the halfway point between a savage and a pompous ass?”

“The enlightened man, caballero.”

The teacher smiled in self-satisfaction as he let the line sink in. My dad nodded in approval and went on, “You’re obviously one of the enlightened. Why don’t you tell me who’s going to win tonight?”

“Cotto! Who else!” growled the teacher.

***

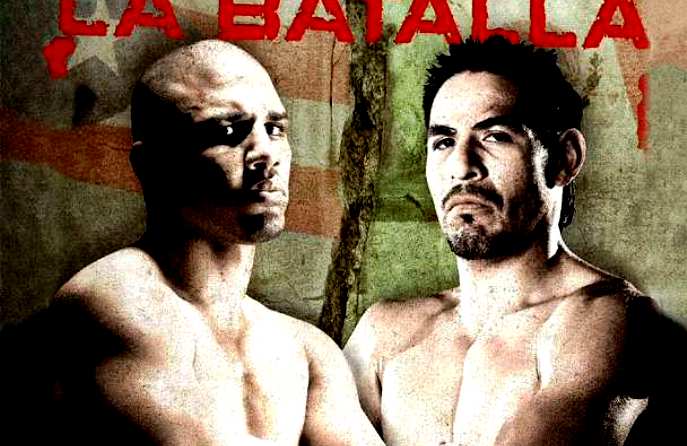

Fought in the summer of 2008, Cotto versus Margarito was billed as “The Battle,” a riff by promoter Bob Arum on “The War,” a fight he promoted back in 1985 between Marvin Hagler and Thomas Hearns that condensed into less than nine minutes more violence than featured in a dozen R-rated action movies from that decade. Or perhaps “The Battle” was simply stating what everyone expected on fight night: a vicious contest between Puerto Rico’s biggest star—an overpowering combination puncher with a killer left hook—and an unassuming but extraordinarily tough fighter whose reputation for stopping punches with his chin matched the heaviness of his fists.

Although every reliable source lists his birthplace as Torrance, California, in the United States, Margarito occasionally tells interviewers he was born about 150 miles south of there, in Tijuana, Mexico. Why he does that is a matter of speculation. He may do it because he feels a keener connection to the land he lived in as a child than to the one his family abandoned when he was a toddler; perhaps it’s a marketing move aimed at increasing his appeal to Latino fans; or maybe he just wants to eradicate every doubt as to the origin of his fighting style. In any case, Margarito grew up in Tijuana, selling newspapers on its infamously dangerous streets to supplement his family’s income. Encouraged by his father, Margarito fell for boxing in Tijuana, a famous breeding ground for cliché-compliant Mexican boxers. When the family budget allowed it, Margarito’s father would take him to boxing cards to check out the local talent; when not, television gave both of them their weekly dose. One time, at a boxing show at the Auditorio Municipal, nine-year-old Margarito watched from the nosebleeds a mob that formed quickly around a single person who slowly walked around the ring trying to find his seat. It took Margarito a moment to recognize who it was, but once he did, he couldn’t believe it. His favorite fighter—the whole country’s in fact—Julio Cesar Chavez, was right there within his sight. Margarito didn’t hesitate in leaving his dad’s side to reach Chavez, who shook his hand, sat him on his lap, and even took a picture with him.

Margarito joined a boxing gym around the time he was eight years old. But his amateur career was cut short—along with any dreams of finishing high school—when he started fighting for money at age fifteen. It was an unusually early age for someone to go pro, even by Mexico’s standards, where fighters often get an early start in the racket for financial reasons. In practice, this guaranteed Margarito would be the younger guy in the ring every time he stepped between the ropes. The hardest part of his apprenticeship came as he faced older, more experienced fighters with longer amateur careers than his own. That’s also when his reputation for being tough as nails began taking shape, and after he’d won enough fights and knocked out enough fellow Tijuanans, he stood out as a hard guy in a town filled with them.

Antonio Margarito was an avoided fighter, one of those cases where the financial reward for facing him and the potential brownie points for defeating him didn’t quite compensate for the risk of losing to him. A relentless brawler who showed no fear of getting hit as he muscled his way inside to land crippling body punches and crashing uppercuts, Margarito didn’t concern himself with winning fights as much as with beating up opponents. In a much-talked-about performance from 2005, Margarito’s gloved fists did to Sebastian Lujan’s left ear what Mike Tyson’s teeth did to Evander Holyfield’s right one almost eight years before. Months later, in his most impressive win yet, Margarito knocked out Kermit Cintron—not an elite talent by any means, but a strong, solid titleholder then regarded as Cotto’s biggest threat in the battle for Boricuas’ hearts and minds. Margarito continued facing ranked welterweights for a few more years, losing only to Paul Williams, a fighter with an otherworldly activity rate. Floyd Mayweather, then king of the welterweights, famously refused an $8 million offer to face Margarito.

In 2008, it was Miguel Cotto who took on the Mexican’s challenge, also granting him the largest payday of his career, with the bout coming to fruition largely thanks to the fact Bob Arum promoted both fighters. The promoter’s decision to put Cotto’s undefeated record at risk against Margarito was welcomed by the boxing public, but also inspired a degree of surprise. After all, Cotto was a much more valuable commodity than Margarito, a proven attraction in New York City and his native Puerto Rico, drawing crowds that Margarito could only dream of. There were even rumors that Oscar De La Hoya himself—fresh off a record-setting mega-fight with Mayweather—was interested in fighting Cotto. Margarito, unlike Cotto, couldn’t count on a significant fan base to prop up his purses. Moreover, he lacked a signature win, and in fact carried around a record blemished with multiple losses, most of them inflicted in the early part of his career when he underwent harsh matchmaking as a teenage professional. Throw in a decidedly unflashy fighting style, his modest attitude and appearance, and a lack of marketing muscle behind him, and you can begin to understand why the proverbial break took so long to arrive for Margarito.

If Margarito, known as Margo, ever considered himself a boxing superstar-in-waiting, he never looked or acted the part. Topped by a hacked buzz cut, his long El Greco face evoked pious humility, with nary a trace of Cotto’s self-assured gravitas, De La Hoya’s boyish good looks, or Mayweather’s cockiness to be found on it. His lanky frame doomed him to suffer to make the 147-pound limit, a potential missed-weight liability no promoter wanted to have to deal with on the eve of a big fight. The very attributes that garnered him something of a cult following were the same ones that made big names look the other way when he came up as a potential opponent. Being a true workingman who always showed up hungry and ready on fight night, and who could give anyone a tough fight, made him too dangerous for more popular boxers.

And perhaps, too, Margarito failed to amass a large fan base because he employed the wrong fighting style at the wrong time. Margarito usually moved and punched a couple of gears behind his rival, as if he alone of the two were fighting underwater. The heaviness of his fists, coupled with his busyness, made up for the disadvantage, but neither economy of attack nor elegance of form was ever in the cards. This anti-nuance, slow-motion stalking was too crude even for Mexican fans, striking them as both atavistic and vestigial. Throughout the first decade of the twenty-first century, Mexican fight fans became enamored with Erik Morales and Marco Antonio Barrera, featherweight superstars who offered a highly technical brand of brawling, as well as with Juan Manuel Marquez and his fearsome counterpunching. Those three names shared more than enough fighting talent to define an era in boxing, and they may have in some way contributed to the refinement of the Mexican public’s tastes. If there’s any truth to that theory, Margarito’s plodding variety of boxing might have appeared to Mexican fight fans to be the comeback of an old, nasty habit that they had battled for years and outgrown. However, if they resented this old habit, those same fans were about to fall in love with it all over when they saw Margarito fight Cotto.

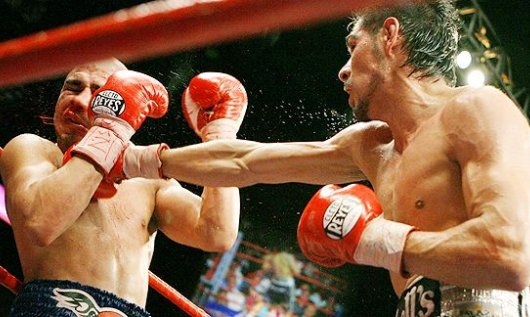

On fight night, Cotto entered the ring as a slight favorite, despite Margo’s considerable size and reach advantage. It’s not usual for the taller and physically stronger fighter to enter the ring an underdog, but in this case the odds reflected the adage that styles make fights: going against the advice even laymen would have quickly provided, Margarito refused to capitalize on the advantage his larger frame and considerably longer arms—he had a full six-inch reach advantage on Cotto—could potentially grant him. The Puerto Rican was undoubtedly the better boxer and the better mover, and it would be up to the lumbering Mexican to play catch-up. The opening round offered nothing to refute that storyline. Cotto took to managing the distance between himself and Margarito, dictating when and where shots would be exchanged. Margarito, on the other hand, seemed to wait until he was close enough to Cotto to count the hairs inside his nostrils before throwing any punches. The stocky, shorter Cotto moved around the ring like a light tank—constantly shifting direction, pivoting this way and that before planting himself to open fire and then moving quickly out of range again. His mark was so accommodating that even Cotto’s straight right—usually a footnote in his plan of attack—arrived frequently and forcefully on Margarito’s face. The Puerto Rican’s confidence grew with every landed shot, so much so that by the end of the first stanza the stoicism that usually permeates his face dissolved just enough to show a faint hint of satisfaction.

What Cotto should’ve kept in mind was that hitting Margarito was always going to be the easy part, especially in the early going. Everyone touched Margarito a bit—manhandled him, even—in the early rounds. While the opening bell represents for most boxers a rude awakening, Margo always considered it his cue to press the snooze button. Proving his understanding that the fight with Cotto was indeed a big deal, this time Margarito allowed himself to doze only until the start of round two and not a second later. In the second stanza, he started landing his trademark left uppercuts, mixing in some left hooks and the occasional overhand right to bring the point home that the fight was officially on. The results were dramatic: at the end of that round, Cotto’s cornermen frenetically swabbed his bleeding nose with Q-tips and similarly treated a subtle cut over the left eyelid that hinted at more trouble to come. From there on, in purely geographical terms, the fight was endlessly repetitive: Cotto retreated in clockwise fashion as Margarito stalked. The problem for the Puerto Rican, as the fight wore on, is that the concentric path he followed in the ring moved further and further away from ring center and by the end consisted of nothing more than continuous visits to the ropes. This played directly into Margarito’s greatest tactical strength, his inside game. In the first half of the fight, Cotto outworked Margarito most of the time, scoring with both hands and landing plenty of eye-catching shots that snapped the Mexican’s head sideways and elongated his neck to cartoonish proportions. But when Cotto stopped moving long enough for Margarito to plant his feet and swing away, the Puerto Rican’s midsection absorbed a barrage of body punches. Cotto grew weaker and weaker with each passing round throughout the second half of the fight.

During the first six rounds, Margarito was consistently outmaneuvered and failed to match Cotto’s punch output. But in round seven, he began throwing combinations the way a seasoned politician makes a speech, giving every blow enough oomph to leave a mark on its audience. Cotto’s quickly decaying facial features attested to the fact that Margarito had taken command. In that round, Margo landed uppercut after uppercut, all of them malicious and powerful, the momentum of his swinging left arm lifting his whole body off the canvas. It was either brutal or thrilling to watch, depending on whom you were rooting for or what side of your brain was calling the shots. It was at this moment, also, that what had been billed as a fight became a rite, as there was little question from that point on as to who was the stronger fighter and who was the weaker, who was the one causing the damage and who was the one getting hurt. Cotto kept fighting, of course, after the turn of the tide in round seven, but for the rest of the night Margarito’s most significant enemy was no longer Miguel Cotto but the timekeeper.

The contest was decided in that brutal round. As Margarito walked back to his corner at the end of the seventh, his face and torso and back splattered with Cotto’s fresh blood, he nodded to the fans celebrating at ringside. It was clear that thereafter all Margarito had to do was keep hacking and chopping away at Cotto, keep grinding him down by pushing him back to the ropes and windmilling away with those long, awkward arms and keep hammering him with those heavy fists until Cotto couldn’t take it any more. And then at some point Cotto would just stop fighting, and that would be it.

That’s exactly the path the contest took. Cotto went from sharpshooter to prey, just as Margarito went from lumbering target to heartless hitman. Margarito’s physicality took control over Cotto’s. Incredibly, the Mexican’s stamina seemed to improve as the fight progressed; he started chasing Cotto on his toes after the Puerto Rican backed away from yet another pummeling combination, while Cotto lay against the ropes more and more, his legs suffering the effects of Margarito’s earlier body work. It all became too much: too much determination from Margarito; too much abuse endured by Cotto; in short, too much one-sided violence. Something had to give. In round eleven, after a minute-and-a-half of nonstop punishment, Cotto took a knee, and he did it because that’s when the truth dawned on him, the same truth that had become evident to pretty much everyone else a few rounds before: taking a knee was the only way he could get a break. Margarito didn’t display fire or rage or fury as he stalked, punched, and hurt Cotto—but rather a relentless and seemingly perverse sense of diligence about getting the job done, which was to drown Cotto in despair, wrap him up in self-doubt, and destroy his will to resist.

For all that, Cotto did get up after taking a knee. Unfortunately for him, Margarito welcomed him back to verticality with more crushing uppercuts. So Cotto did what anyone else in his situation would’ve done: he went back down on his knee again. This time, however, he wasn’t looking for respite; this time his taking a knee signaled a cry for help. His uncle and trainer, Evangelista Cotto, obliged, throwing in the proverbial towel and ending the fight with fifty-five seconds left in the next-to-last round.

— Rafael Garcia

Great article….more please. Margo is an enigma for me…I wish to know to what level did his criminal behavior extend to? (like was it more than once I mean). Some insiders (Dougie from Ring Magazine fro example) suggest that his trainer wasn’t smart enough to break the rules and not get caught and that the Mosley fight was his first and only time such a deplorable action was taken.

Cotto versus Margarito II is one of my all time favorite fights…Cotto was brave as fuck to make the fight and then cold as all hell to avenge that horrific loss over the brutal bully in such smart fashion.

“Cotto went from sharpshooter to prey, just as Margarito went from lumbering target to heartless hitman…. He didn’t display fire or rage or fury as he stalked, punched, and hurt Cotto—but rather a relentless and seemingly perverse sense of diligence about getting the job done, which was to drown Cotto in despair, wrap him up in self-doubt, and destroy his will to resist.” Tremendous piece of writing from one of the best modern-day boxing scribes in the biz. Great work, Rafael. Take a bow, sir.