Feb. 2, 1980: Sanchez vs Lopez I

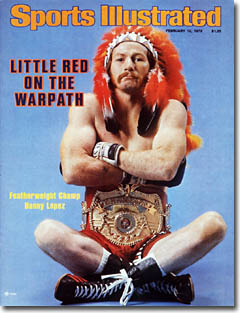

Danny “Little Red” Lopez had won the WBC version of the featherweight crown in 1976 and no one begrudged him the title. This was because Lopez, contrary to the stereotype of the merciless, one-punch knockout artist, was as nice a guy as you could ever meet in boxing. Respectful and unassuming, “Little Red” quietly went about his business which involved dishing out some shattering right hands to his opponents, though often not before getting a bit roughed up himself.

The story of Danny Lopez is one we’ve heard many times before, one that almost redeems the brutal and heartbreaking racket called prizefighting. Boxing gave Danny a means by which to make something of himself, to rise above his impoverished childhood. He grew up living with seven siblings in a two-room shack on a native reservation and spent time in jail for assault and battery before being shuffled off to a foster home. His older brother Ernie boxed and would eventually challenge the great Jose Napoles for the welterweight world title, so when Danny was sixteen, he simply made up his mind to follow the same path. He embraced all the discipline and hard work the profession demands and ever after, there was no more trouble with the law. Five years after he turned pro, and with wins over Chucho Castillo and Ruben Olivares on his record, there he was, in Ghana of all places, overwhelming David Kotey for the featherweight championship of the world.

The title reign of Lopez was distinguished by the thrills he gave fight fans, both when he was taking punishment and then dishing it out. A slow starter, Danny usually looked vulnerable in the first round or two, eating punch after punch, before he found his rhythm and started making the other guy pay dearly for his transgressions. Soon enough a thunderbolt knockout followed, courtesy of his vaunted right cross, prime examples being his bouts with Kenji Endo or Juan Malvares. Before his Waterloo in the first Sanchez vs Lopez match, Danny defended his title eight times, in the process becoming one of the most popular boxers in America, his bouts earning high ratings on national television. No one expected anything different for Danny’s ninth title defense, broadcast live on CBS from Phoenix, Arizona. Another obscure challenger, surely another knockout for “Little Red,” right?

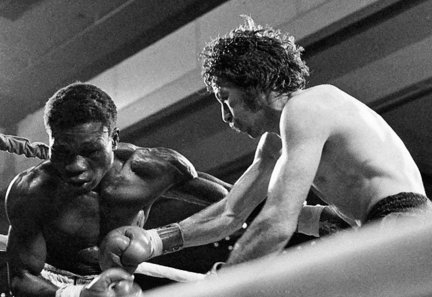

But it didn’t work out that way. No one north of the border could know it at the time, but the 21-year-old Salvador Sanchez was much more than just another contender. A gifted counter-puncher, Sanchez had patience and maturity beyond his years, along with quick hands, exceptional stamina, and a rock-solid chin. As early as the second round, it looked like it was going to be a long and painful afternoon for Lopez as the challenger connected far too frequently with damaging power shots, especially the counter right. The loyal fans of “Little Red” waited patiently for his trademark comeback, but by round four Danny’s left eye was swelling shut and by the sixth a bad cut had opened over the right.

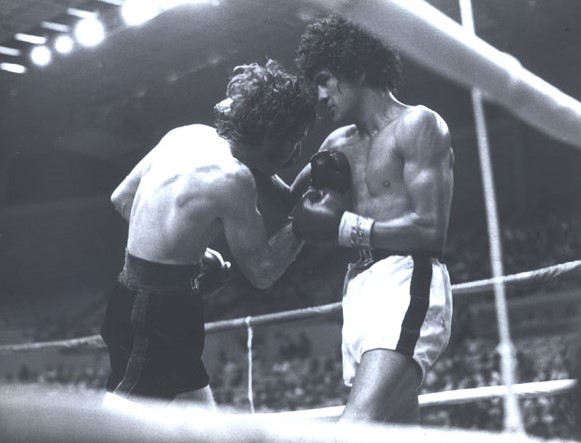

The battle was fast-paced but one-sided. Bouncing on the balls of his feet, Sanchez would move in with the cool efficiency of a remorseless assassin to land his left hook or counter right and then, just as swiftly and smoothly, move out of range. Lopez never stopped trying, but he lacked the quickness to connect with force and consistency. In round seven the action heated up as Sanchez, with no fear of the Danny’s power, elected to stand and trade and “Little Red,” game as ever, took the fight to the challenger. But while both men were throwing big punches, the only one scoring clean shots was Sanchez. At the end of the round an overhand right buckled the champion’s knees.

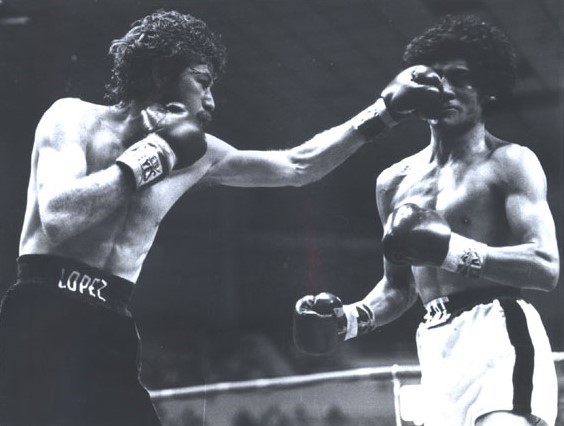

It was more of the same in rounds eight and nine before Lopez finally asserted himself in the tenth, backing Sanchez up and timing his right hand better. But he couldn’t hurt the unflappable challenger and the following round saw a return to a clinical beat-down from Sanchez. The sheer number of clean, sharp blows Lopez was taking had to be alarming for both his fans and his corner, not to mention the millions watching on live television, but, as everyone knew, there was no quit in “Little Red.” His only hope now was that Sanchez might tire, but the Mexican appeared just as sharp in round twelve as he did in the first. By this point he was hurting Lopez in almost every exchange, but Danny never stopped trying to land the one big shot that might turn things around.

In round thirteen two clean rights staggered the champion yet again and the referee, knowing Lopez had to be saved from his own courage, stepped between the fighters to raise the hand of Sanchez. The gifted boxer they called “Chava,” perhaps the greatest of all the great Mexican boxers, would then embark on an extraordinary run, ten title defenses in fewer than eighteen months, including a rematch win over Lopez and victories against such formidable battlers and champions as Ruben Castillo, Juan Laporte, Wilfredo Gomez and Azumah Nelson. Killed in a car accident in 1982, the title he took from Lopez with such authority was his until the day he died and Salvador Sanchez will forever be regarded as one of the greatest champions in featherweight history. – Neil Crane

Beautiful

Thank you