Manny Pacquiao: You Had To Be There

With the buzz of a possible comeback for a 45-year-old Manny Pacquiao rising in volume, the time is right to be unequivocal: the Filipino ring legend who won world titles in an incredible eight different weight divisions should, for the sake of his health and his family, stay far away from the roped square. And for one simple reason: he has done it all. Another reason: while competitive against Yordenis Ugas back in 2021, he looked every bit of his 42 years; how can he hope to perform better at the age of 45? No, we do not want to see Manny Pacquiao return to the ring, but instead want to remember him as the extraordinary fighter that he was. So herewith, our tribute article for “The Pacman,” featured after his defeat to Ugas and subsequent retirement. The memories are still fresh, still extraordinary, of a career unlike any other in the history of pugilism. Please, Manny, let’s keep it that way. Check it out:

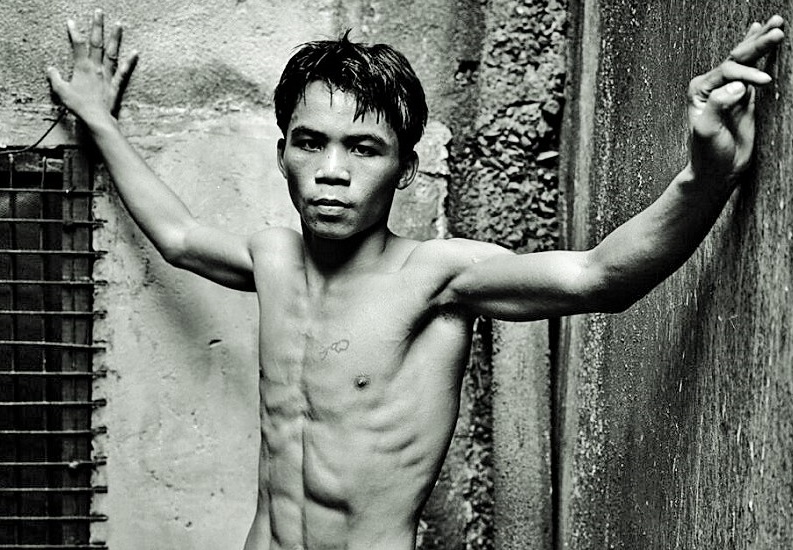

You’ve seen it. The photo taken when he was sixteen, standing in a corner, staring at the camera, hard to tell whether in defiance or hope. He’s skinny, wiry, all sinew and muscle and bone. His face is a kid-version of the one millions around the world would come to know and cherish. His hair parted off-center, his nose already a bit flattened by sparring, his expression stoic, his eyes piercing. Prophetically, in this picture, taken before he had ever been paid to lay leather on someone else, he already sports a tattoo of a small boxing glove, righteously situated on top of his heart. There is no way he can know how apt and profound this chosen tattoo will become.

Manny Pacquiao would come to define boxing for an entire generation. Not only was he the face of the sport for a long period of time, but he came to personify what so many love about boxing: the courage, the violence, the knockouts, the willingness to challenge himself against the best opposition, time after time. His million watt smile charmed the masses while his lightning-fast fists pummeled his opponents. For a while there, for a long while, Manny Pacquiao seemed inevitable, invincible, unstoppable. And somehow bigger than boxing.

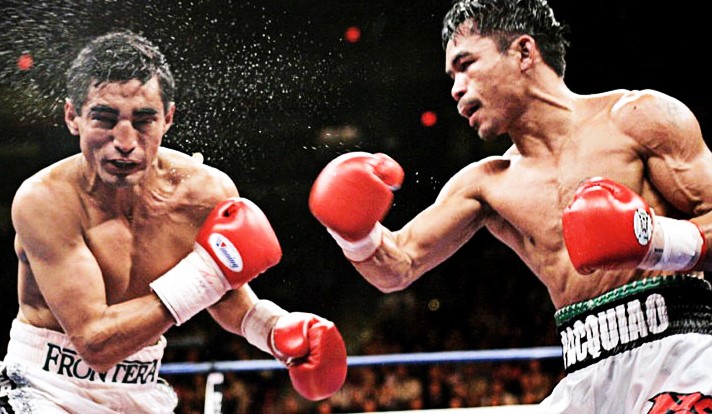

You had to be there. Like I was, on a cool January night in Vegas when Manny Pacquiao met Erik Morales in a rematch of a bout Manny had lost less than a year before. The widespread perception of that first great battle was that the Mexican legend had taught the young up-and-comer a much-needed lesson, punishing him for the insolence of his having beaten up Marco Antonio Barrera, and for dropping Juan Manuel Marquez three times in a single round. It was as if “El Terrible” had laid down the law, telling Manny, “Yeah, you’re good, but you still have a lot to learn to be on my level.”

Morales must have been astonished at how quickly the Pacman learned his lesson. In the rematch, it was the Filipino who dominated, landing crisp blows round after round, the intensity of his attack only increasing as the fight progressed. Pacquiao wore Morales down until the brutal end came in round ten and the Vegas crowd, already made up in large part of Filipino faithful and roaring with every punch from their hero, exploded in sheer ecstasy when the Mexican great capitulated. What had started as a cult had now turned into a full blown religion, and it was open to all.

You had to be there, and you had to pay attention to realize the full extent of Manny’s powers. The violence of his ring exploits was what drew the masses, sure, but behind it was craft and ring intelligence that aged like wine. As time passed and the pounds piled on, as the rivals got bigger and better, Manny Pacquiao adapted, fine-tuned his game, added new dimensions and nuances, as only an all-time great can.

It all began with that lethal left hand, the one that floored opponents before they realized what had happened, the one that busted their noses and rattled their brains. But then Freddie Roach began working with Pacquiao and the Manny & Freddie team, perhaps the most accomplished boxer-trainer duo of the 21st century, kept improving the southpaw’s form, fight after fight. Like kids at a candy store gleefully filling their bags, they kept adding weapons to his arsenal, like the right hook Freddie dubbed “Manila Ice.” They added feints, and body shots, and head and waist movement. It’s almost unfair how they managed to jam so much power and speed and trickery into a single package.

And what about that footwork? Fancy enough to render Michael Jackson jealous. The speed of Manny’s feet, the quickness with which he moved in and out of range, the lateral movement, the angles. The way he punched, moved to the side, and punched again, this time standing perpendicular to his foe, who was still trying to figure out where Manny had gone and who was attacking him now from the flank. To fans it felt unprecedented, refreshing and new, in a sport so rich in history that we pride ourselves in thinking we’ve seen it all.

And there was still so much more to see. Manny ran roughshod over the competition at featherweight and super featherweight. He dispatched two of the three Mexican legends–Morales and Barrera–convincingly. The other one, Captain Ahab to his Moby Dick, was Marquez, who kept stubbornly rising up from the canvas, who kept counterpunching him, who kept stealing enough rounds to maintain a vexing stalemate. The conclusion to that rivalry would have to wait.

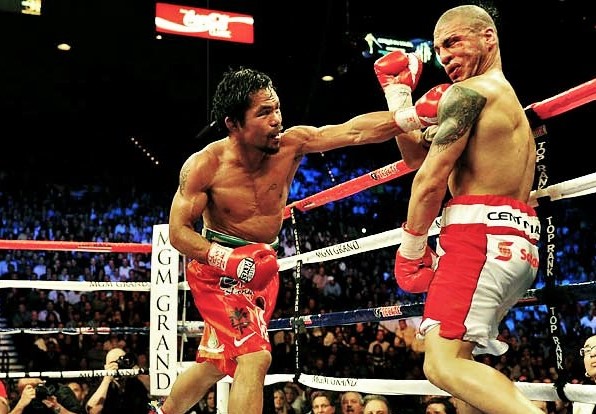

Looking for bigger game, Manny crashed the welterweight division and everyone thought going after Oscar De La Hoya was both a cash grab and a fool’s errand, “The Golden Boy” too big and too strong for a guy who had begun his career at 106 pounds. As things turned out, Oscar never had a chance. Then Manny went down to 140 pounds–as simple for him as pushing the down button in an elevator–to crush Ricky Hatton in two rounds. Then back to welterweight to dominate Miguel Cotto, and then up to 154 to maul Margarito, earning a belt, but also suffering a rib injury at the hands of the much bigger man and he vowed never to fight above 147 again. After having journeyed through an astonishing twelve divisions, Manny Pacquiao had finally found his ceiling.

It was at this point that Floyd Mayweather Jr. re-entered the picture after having exited the game in a premature retirement. It was a confrontation that ignited the imagination of millions: the defensive master against the fearsome attacker, the immovable object against the unstoppable force. But issues got in the way, too many to count, all of them equally irrelevant. In all likelihood, it all came down to money: they couldn’t figure out how to split a nine-figure sum, and thus, we waited.

Boxing fans seldom get what they want, but sometimes we get what we need. And what we got while we waited for Manny and Floyd to sort out their business was one of the best rivalries of modern times. Manny and Marquez met for a third time in November of 2011, and I was there that time too. The crowd at the MGM Grand was split into two factions, the Mexicans and the Filipinos, with tickets selling at a considerable markup from 2006, hotel rates through the roof, casinos so packed that the fire code became a mere suggestion. Only a handful of fighters are lucky enough to star in a single Vegas extravaganza in their careers; Manny did it over and over through his prime. Just another day at the office for the fighting marvel from the Philippines.

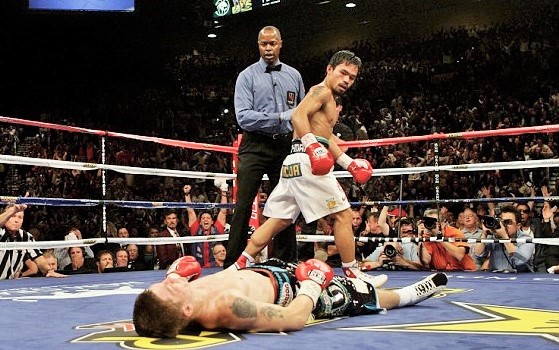

If Manny and Marquez had wanted to put a stamp of clarity on their rivalry and decide things once and for all, the trilogy fight rendered it only more confused. While most thought Marquez deserved the verdict, the judges awarded Pacquiao a dubious one. Let’s run it again, they said, while many of us groaned. But the fourth meeting was their most spectacular, packing into slightly less than six rounds more action and violence than fight fans have a right to demand. A single punch from Marquez sealed the rivalry forever; Ahab finally caught the whale. The outcome was so final, so conclusive, that we deemed it impossible for Manny to come back. The image of him lying on the canvas face-down, immobile and helpless, seemed unnatural, frightening. How can anyone come back from that?

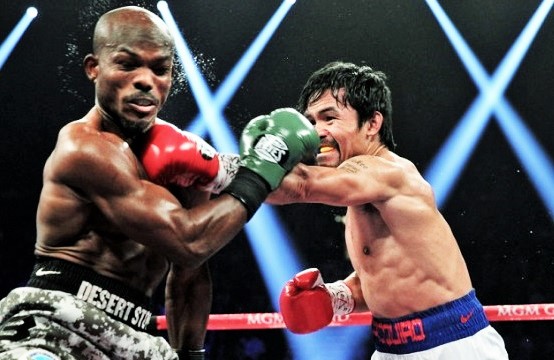

But Manny did come back. He finally got his chance to take on Floyd, and most of us cannot recall a single notable moment of that colossal disappointment; all we remember is the hype. Doesn’t matter, because Manny Pacquiao still wasn’t done. And if he was no longer the knockout machine of years past, he was now a smart, mobile boxer-puncher, with loads of experience, happy to battle a crop of younger fighters who hoped to grab a piece of what had taken the Filipino legend years of combat to earn. At an age when the vast majority of past greats had no choice but to retire, Manny still had more than enough to vanquish the likes of Chris Algieri, Timothy Bradley, Jessie Vargas, Lucas Matthysse and Adrien Broner.

The most significant win of the Pacman’s last act was a convincing 2019 victory over Keith Thurman, a talented boxer who once upon a time had many believing he was the legit heir to the welterweight throne. Manny had no business going after someone like Thurman, a truly formidable foe, at that point of his career, but he did. As if his amazing record needed any more defining moments, or any more big names on it, as if his trophy case needed any more scalps.

Why did he do it, then? Maybe because his attitude towards his career was the same as his fighting style: best to go all in than to hesitate; best to leave it all in the ring than to step out of it with regrets. It would be sinful to not fulfill the potential God had bestowed upon him. In the ring Manny left no questions unanswered, he sidelined no rival, he granted as many rematches as were requested. Win or lose, he always gave his all. His goal as a prizefighter was to win, yes, but contrary to what Lombardi dictated, winning wasn’t the only thing; just as important for Manny was to win his way.

And his way was to go after the other guy from bell to bell, to never stop trying to punish him and send him to the canvas. More than fitting for a warrior who tattooed a boxing glove on top of his heart, not to mention a way that carried him to the very top of the toughest sport there is. One that filled his bank account beyond any dreams he might have had as a skinny teenager, when he had to fill the pockets in his shorts with rocks in order to make weight and be allowed to fight. One that made his legions of fans happy, and kept them coming back for more. You had to be there, but we were all there, we all saw it, watched a young fighter become a champion and then something more. We all saw it and we may never see its like ever again.

Manny Pacquiao came from nothing, he left with everything, and we loved him because of all he gave to the sport, because of all he gave to us. My, oh my, what a fighter Manny Pacquiao was. — Rafael Garcia