May 29, 1901: McGovern vs Herrera

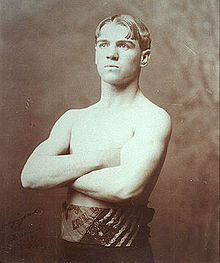

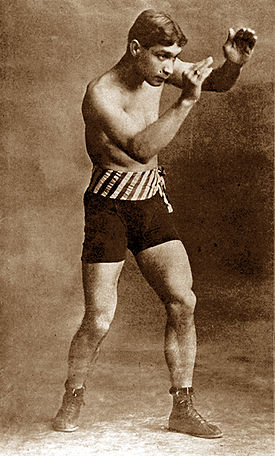

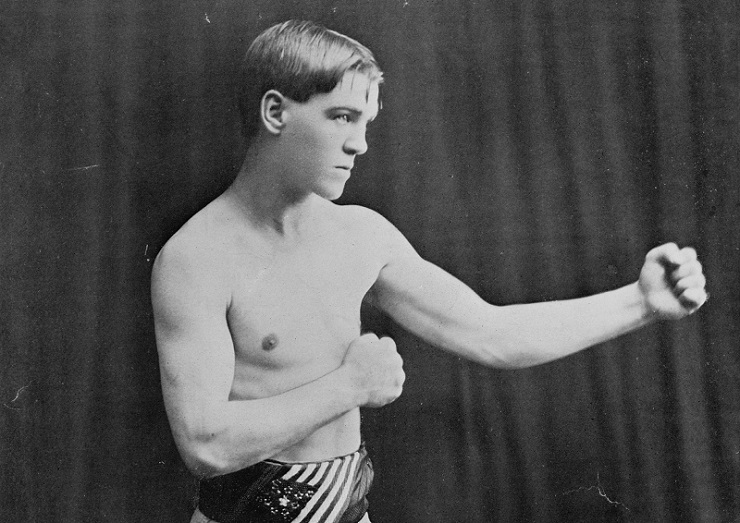

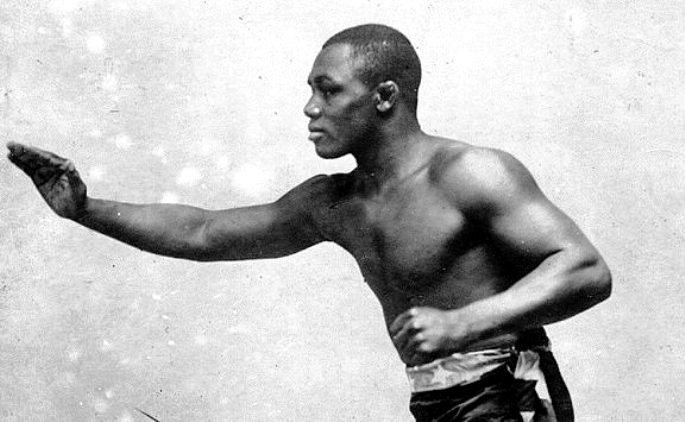

In one corner is a bigger-than-life character, a two-division titlist and miniature wrecking ball defeated only by himself in two disqualification losses. And in the other corner, an unlikely star guided to success despite growing up in the seediest of environments. Featherweight champion Terry McGovern and challenger Aurelio Herrera collided at just the right time at Mechanic’s Pavilion in San Francisco, as impossible as the end result may make that seem.

Frank Carrillo, who had guided Herrera’s career to a then-stunning record of 32 wins with 30 knockouts against only two draws, wanted his charge in with “Terrible” Terry sooner rather than later, as Herrera had trounced a boisterous lightweight named Toby Irwin in eight rounds the month before. The resounding victory over Irwin coupled with McGovern’s hiatus from the ring and subsequent outside ventures meant the opportunity to challenge for the featherweight title had to be taken, if presented. If nothing else, Herrera could swat, and facing another offensive-minded fighter meant the chance would be there to land.

McGovern’s December, 1900 win over the great Joe Gans was labeled a “fake fight” by The Chicago Tribune, and the result was boxing’s long-term banishment from Chicago. McGovern then headed to San Francisco, considered at the time still one of the more lawless of American cities, and banking on his fame, joined the acting cast at the Central Theater for a production called “The Bowery After Dark,” a play about the watering holes and brothels of the famous red-light quarter of New York City. McGovern played the role of the Bowery Boy, a foolish simp who moved the story forward with narration and then snagged the audience in the final act by sparring for four rounds with his training partner, Danny Dougherty. Clearly, if there was a time for Herrera to catch the champion lazing, this was it.

A few weeks of training at the Olympic Athletic Club just blocks from San Francisco Bay suited McGovern just swell, while Herrera trained down south in San Jose with Tim McGrath, a well known manager and trainer who steered “Sailor” Tom Sharkey to success. McGrath told reporters, “I have seen all the 126 pounders on the coast and want to tell you that Herrera is the best of the bunch.”

One day prior to the contest odds were pegged as 10-to-4 for the reigning champion, but it was reported throughout the week that Carrillo had been taking on four-figure side bets at odds much steeper than those, confident in his 24-year-old boy’s ability to render foes horizontal.

The San Francisco Call dedicated plenty of ink to advertising and reviewing “The Bowery After Dark,” but little to McGovern vs Herrera until it was upon the city. On May 28th, The Call boldly stated that, “Herrera will carry the hopes and the dollars of the entire oil belt on his shoulders. That he will do his utmost to achieve a victory is beyond dispute. He is an ambitious youngster and is possessed of a punch which if it lands on an opponent cuts short his aspirations.”

Clear from the onset, though, was that Herrera just didn’t belong in the same ring with McGovern. Not on that night, anyway.

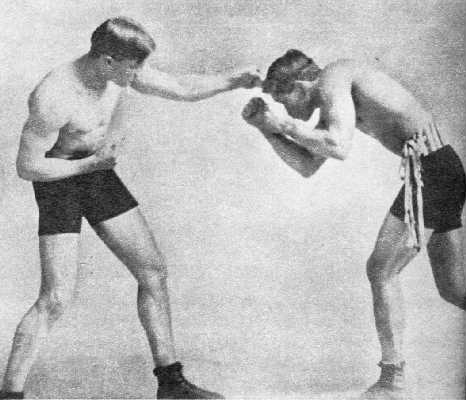

The Evening Tribune reported, “The fight had not progressed one minute of the first round before it became evident to all that McGovern was not making an effort to end the contest, but was content with buffeting Herrera about the ring at his pleasure.” McGovern moved his hands, but seemed to be toying with Herrera between forcing him to the ropes and alternating between landing upstairs and down. At the bell, Herrera smiled at McGovern and shook his head, suggesting he could stay in at the pace.

Round two confirmed that Herrera was wrong. When Herrera landed one, McGovern landed two; when Herrera lashed out, McGovern suppressed his efforts by pushing him back and landing hard to the body. While reports noted that Herrera had skill with his hands, they also said his mobility was limited compared to McGovern, who moved near and far with ease. The third round saw McGovern either unable to rock Herrera despite a number of hard punches landed, or laying up with his power slightly as the game challenger was for the second round in a row clinching repeatedly and groggy at the bell.

The referee, Phil Wand, would later state that he felt McGovern was taking no chances, and The San Francisco Call said McGovern was “careless on defense” in basically sparring with Herrera and sizing him up for a knockout through four rounds. But McGovern was doing something he did often and did very well: every time the fighters collided, McGovern would get a hand free and punch at whatever he could, and at the call of “break,” he would throw a right hand. One such blow connected before the gong, sending Herrera to his corner a bit spongy once more.

If McGovern truly had been carrying Herrera, as was widely suspected afterward, then in round five, he clearly dropped him. A right-left combination from McGovern sent Herrera to the canvas for a nine count, and upon getting to his feet Herrera was met with another barrage and grabbed the champion to stay upright. After doing so, another couple of punches put Herrera down again, and convinced him to stay there. As The Call put it, “In the fifth round Herrera genuflected to an accompaniment of second counts. He might have raised himself to his feet, but he was not in the mind for it.”

McGovern blamed what he rightly anticipated would be read as a poor showing on Herrera’s holding and inability to scrap it out, though Carrillo complained that Wand let McGovern get away with hitting on the break and other fouls. In the end, Herrera wasn’t ready for a fighter of McGovern’s class, but there was no shame in that. Herrera still went on to draw well outside of his comfort zone in over 60 more bouts, generally only losing to experienced or classy toughs like Abe Attell, Billy DeCoursey and Kid Goodman. Fact is, he got in with “Terrible” Terry while it still meant something.

After more time spent lazing and banking on his reputation, McGovern got flattened in his next bout, a wild two round affair with Young Corbett II. In 1903 he met Corbett again but with a similar result, Corbett scoring a clean knockout in round eleven. McGovern would never again challenge for a world title. He would end his career in 1908, not having won since 1905.

Herrera, later called “The Mexican Skull-Crusher” by The New York Times, despite the fact he was American born, got roundabout revenge for his loss to McGovern by stopping Corbett in 1906. He then faded away. Both featherweights succumbed to fast living, McGovern at 37 and Herrera at 50. But the tale of those five hard-fought rounds in Frisco endures. — Patrick Connor

Inspiring, I was raised on those stories!

Been involved in boxing 75 years, still am!