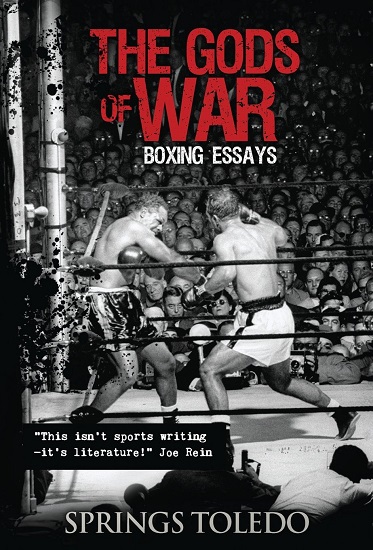

The Gods Of War

One of the best parts about being a boxing fan is the vitality of the sport’s history and the spirited debates and discussions that arise from it. The arguments about who was better and who was best; the endless comparisons of different eras; the bold challenges of long-held assumptions — all a huge part of the pleasure of following the fight game.

Of course writing is a big part of this, and one mark of a good boxing book is it helps to spark new debates. The Gods of War by Springs Toledo scores high when it comes to offering up provocative ideas and assertions. And while the collection does have its weaknesses, some of those are the very things that engender lively debate; after all, disagreements can lead to great conversation.

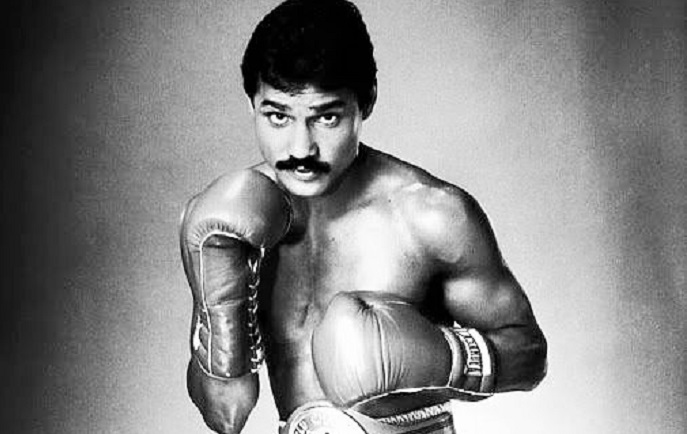

Toledo is at his best when recounting specific anecdotes from boxing’s past, and that’s just how the book starts. In this first section of essays entitled “The Immortals,” he provides plenty of lesser-known stories that make for fascinating reading. For example, when he discusses the great Jewish fighters of the 1920s and 30s, he recounts how in 1929 a synagogue in Hebron was ransacked by a mob that murdered 67 Jews. Back in America, the boxing community staged a benefit card headlined by five Jewish fighters, all of whom won their bouts. In his essay about Alexis Arguello, Toledo recounts how the day after “El Caballero del Ring” beat James Busceme, in Busceme’s hometown no less, the loser of the match went out to celebrate his 30th birthday. Arguello, who’d stopped his opponent in the sixth round, learned where Busceme was having his birthday dinner and brought him a cake. Gentleman of the ring, indeed.

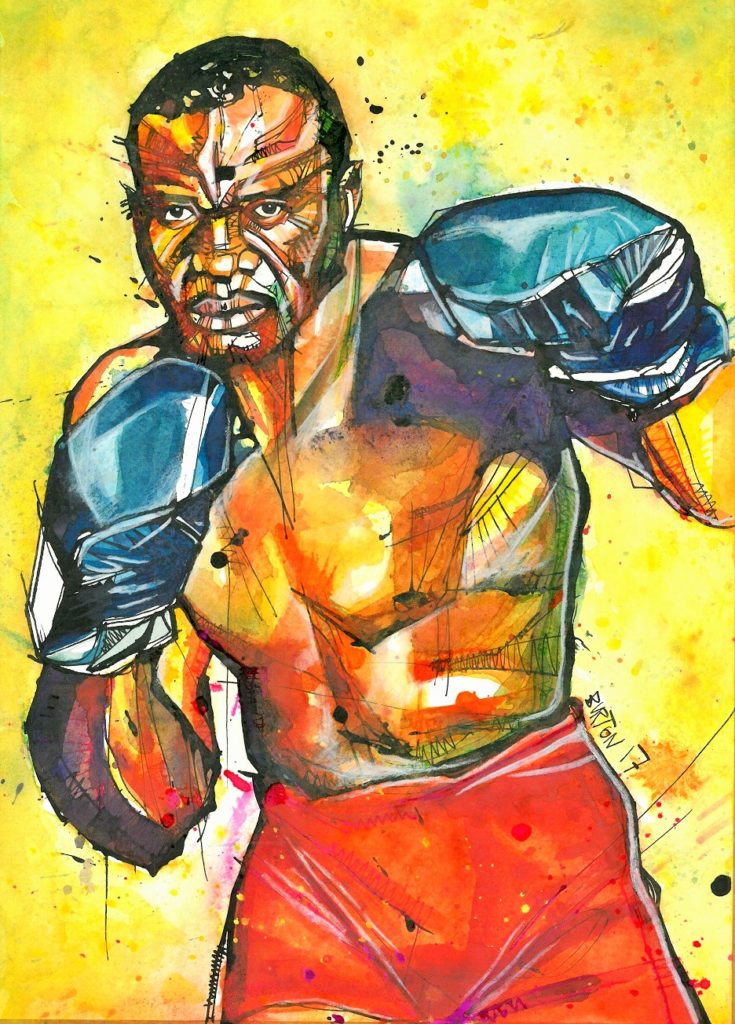

After seven such entries on different topics — Joe Frazier, Kid Chocolate, a trainer called “The Nonpareil Hilario” — Toledo goes into a series of four essays about Sonny Liston, which is perhaps the strongest section of The Gods Of War. Again, it is the accumulation of small but significant anecdotes which make these essays so good. In one, Toledo recounts how Liston, in order to secure a shot at the world title, knew that instead of calling out the champ, Floyd Patterson, he had to confront Patterson’s manager, Cus D’Amato, and so took a train to New York in order to do just that. When D’Amato gave Liston a list of managers from whom the challenger could choose, Sonny just replied, “Ain’t that nice. What you mean is that you want to control me.”

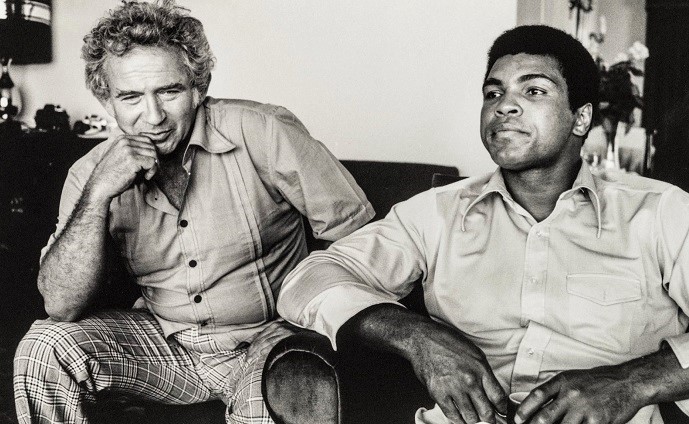

Perhaps the book’s high point is the essay entitled “The Conquering Sonny” in which Toledo makes his case for Liston being underrated in the pantheon of heavyweight champions. He discusses Sonny’s physicality: “[he] threw punches like medieval catapults threw boulders”; his technique: “Ali himself conceded that Liston’s brutality was scientific”; and his intangibles: “Cleveland Williams broke his nose in the first round … [b]lood poured like lava, but from the expression on Liston’s face, it looked like he was playing poker.” Toledo makes a compelling argument that, because Liston had been ducked by so many and for so long, his performances after reaching the pinnacle of the division fail to accurately represent his greatness.

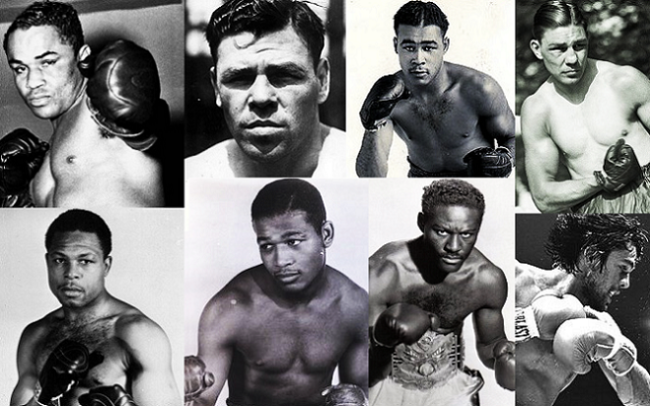

This meditation on Sonny Liston’s place in the heavyweight pantheon serves as a segue into the final ten essays of the book which are about the pugilists Toledo considers the ten best in the modern era, the titular “Gods of War.” Toledo’s analysis of Liston stands on firm ground, but as he makes the case for his historic, pound-for-pound rankings, he cedes some of that strong position and wades into the class-five rapids of objectively trying to grade boxers of different eras.

The first concern is his definition of the modern era, the beginning of which he marks as May 25, 1920 with the passage of the “Walker Law” in New York. This legislation standardized weight divisions, mandated scoring decisions be made by referees and judges, and created a state athletic commission, among other regulations. No doubt the law is significant in the development of professional prizefighting, but it’s difficult to see it as a clean break that led to immediate consequences for how boxers boxed, in a fashion similar to say the “dead ball” to “live ball” shift in baseball in 1919. Great pugilists who competed prior to 1920 — such as Joe Gans, Jack Johnson, Sam Langford, and Jimmy Wilde, just to name a few — are not included in Toledo’s rankings, but no doubt many fans and scholars of the game might consider them “modern” boxers.

The second issue is Toledo’s criteria. He ranks boxers on the following basis:

1. Quality of opposition, 25 points

2. Ring generalship, 15 points

3. Longevity, 15 points

4. Dominance, 15 points

5. Durability, 10 points

6. Performance against larger opponents, 10 points

7. Intangibles, 10 points

These are undoubtedly all qualities of any great pugilist, and fans could debate this list endlessly, but Toledo puts forward his process and resulting rankings as “definitive.” For various reasons, including those stated earlier, it’s difficult to see any ranking of great fighters as definitive, and for Toledo to assert his as being so gives his work an air of arrogance that, whether he realizes it or not, undermines his assertions. This is one quality that in fact inhibits lively debate and discussion and puts the emphasis on the writer, instead of where it should be, on the fights and the fighters. That stated, there’s no questioning that his ten “Gods of War” are among the finest boxers who have ever lived and the ten resulting essays stand on their own considerable merits.

However, when considering Toledo’s wider ranking of his top 30 modern boxers, questions do arise. For example, Muhammad Ali comes in at number 12 and Joe Louis at 13, but above them at number ten is Charley Burley, who never won a world title, primarily because he was ducked by the champions of the time. But I can’t help wondering how Burley might have handled a world title and the pressures associated with it. Likely he would have been a great champion, though success can do strange things to athletes, but the point here is that we know for certain that Ali and Louis (not to mention many others unmentioned in Toledo’s ranking) rose to the occasion again and again, and proved themselves the very best in their division over an extended period of time. One cannot say the same for Burley.

I would have liked Toledo to address directly such counter-intuitive elements of his ranking, but instead all Toledo says is that if your favorite boxer doesn’t make the list, “understand that it doesn’t mean he isn’t ‘great’; it merely suggests that there are others still greater.” A fair sentiment, but to me this is somewhat dismissive of disagreements Toledo knows his readers will have. I’d prefer to see him steel-man them than avoid them, and considering the author’s vast knowledge, I suspect he could do just that.

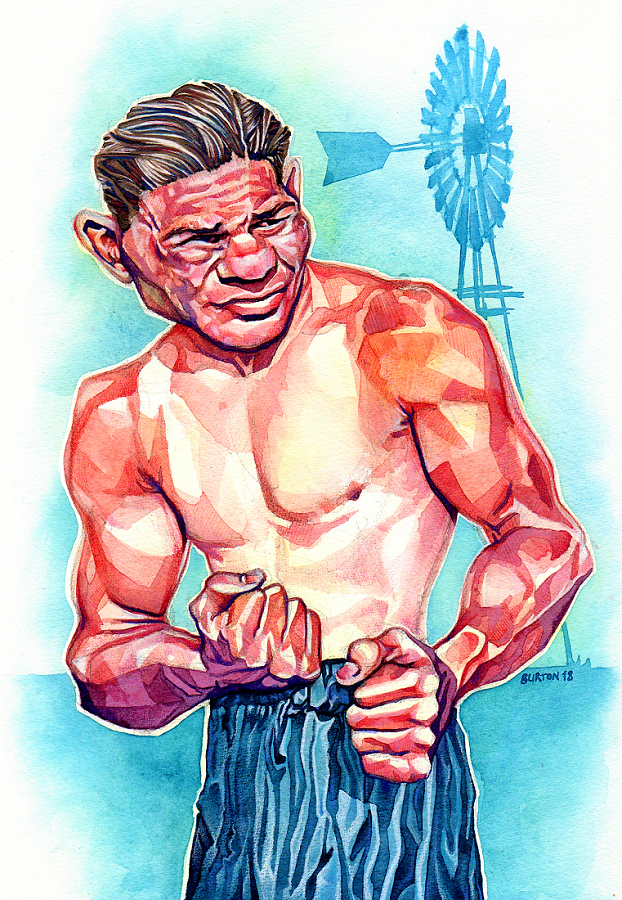

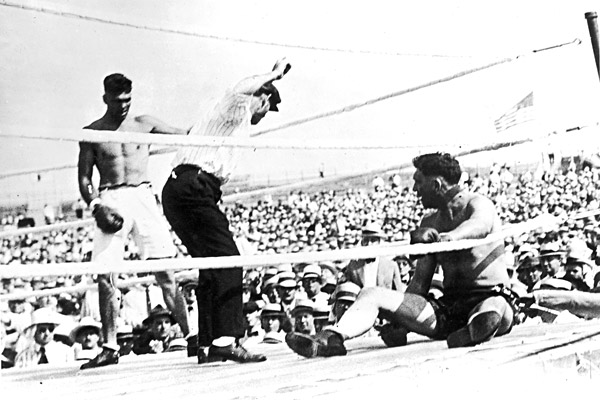

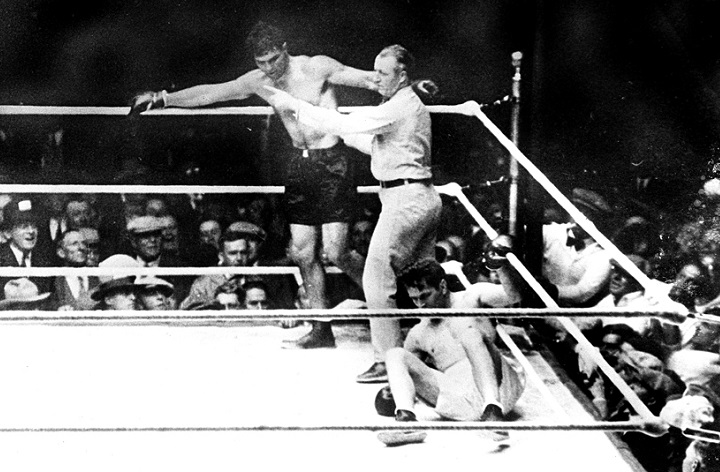

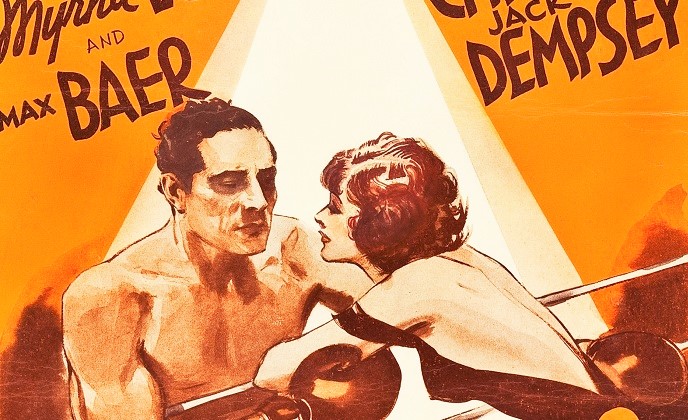

The author’s unwavering confidence may be a factor in another flaw of the book, namely his propensity to slip from the persuasive to the pretentious. Toledo has the ability to show us a fight or a fighter’s life with clarity and eloquence, but he can also take a tad too much delight in his own linguistic flourishes. For example, he frames his essay “Fireworks and Falling Giants” around the Fourth of July holiday as it was the date of Jack Dempsey’s battering of gigantic Jess Willard, and his conceit results in numerous revolutionary comparisons.

Recalling Gunboat Smith’s fight against Willard, Toledo writes: “Like Smith, General George Washington spent the early part of his struggle against a superior force attacking and losing.” Then later: “Willard’s fight plan was similar to Great Britain’s in that it was both conservative and overwhelming.” While such references can be clever, they soon become tiresome and overall the author does this sort of thing too frequently for my liking. I do not deny Toledo his fine moments, and he has many, but for me the prose too often takes center stage at the expense of the subject matter.

Springs Toledo is an extraordinarily knowledgeable boxing writer, and even with its flaws, The Gods of War made me think and want to talk with other fight fans about the book and what I’d read. Its a volume that entertains while spurring deliberation and discussion. This isn’t about being right or wrong; it’s about keeping up the conversation, and in that respect Toledo has succeeded admirably. — Joshua Isard

I read Rope Burns, best boxing short stories ever. I also read Fat City as a kid and it imprinted on my brain. Then Somebody Up There Likes Me, The Black Lights, and all the great reads in Boxing Illustrated. I’m battling to finish the Hagler story, boring as batshit. Someone with a handle like ‘Springs Toledo’ gotta have a big opinion of himself. I’ll pass.