Women’s Boxing: Not For Everyone

Perhaps I’m a dinosaur, a relic of the Dark Ages, but women’s boxing just doesn’t interest me. While holding such a heterodox view won’t get you burned at the stake, it will induce reflexive sneers from righteous pundits and fans, along with a side-order accusation of misogyny. If you love boxing, the reasoning goes, why does the gender of the principals even come into play?

I’ve been pondering this question myself, and in truth, there’s more than one reason why women’s boxing is not for me. Firstly, though, I should clarify that I don’t oppose it on ideological grounds. I’m not one of those people who claim that boxing is “a man’s game.” It’s just that I don’t take any particular interest in it. Don’t read about it, don’t watch it, and could probably count the number of female boxers I’m aware of on two hands. The way I see it, women’s and men’s boxing are almost two different sports – but more about that a bit later.

First, some due diligence. Ahead of writing this piece, I thought it was only fair that I sit down and watch some high-profile female bouts, specifically the Claressa Shields vs Savannah Marshall showdown, and this year’s – and arguably history’s – biggest: Katie Taylor vs Amanda Serrano at Madison Square Garden, the contest that Sports Illustrated’s Chris Mannix claimed was not only “the best women’s fight of the year; it was the best fight.” How Mannix could know there would be no greater contests held in the remaining months of 2022 is a question I’ll leave others to ponder. Of course, I had been aware of the hype surrounding both of these match-ups at the time, though I felt no real compulsion to tune in.

At stake for the Taylor vs Serrano clash was the Irishwoman’s unified lightweight title. An Olympic gold medallist, Taylor had acquired her maiden world championship in just her seventh pro fight, and only her third outing against an opponent with a winning record. Puerto Rican veteran Serrano, meanwhile, had won various world honors in multiple divisions, at one stage having three back-to-back contests in different weight classes: super lightweight (140 pounds), super flyweight (115), and featherweight (126). Incredibly, these all took place within the span of twelve months.

I fired up YouTube and watched Taylor vs Serrano with an open mind and the rounds breezed by. It was a damn good battle between two well-matched, well-rounded fighters, Serrano the hunter and Taylor the counterpuncher. The fifth round was a wild brawl. Would I watch the rematch? Absolutely. Am I going to religiously follow their careers from this point forward? Probably not.

Shields vs Marshall headlined the UK’s first all-female pro card this past October. Shields calls herself the GWOAT (Greatest Woman Of All Time) despite having had just thirteen pro fights, though she did win two Olympic gold medals. The American acquired the unified world middleweight title in her fourth bout, and Marshall was also a belt-holder, having claimed a vacant championship in her ninth outing against a foe with a 9-4 record. Interestingly, Shields managed to capture world titles in three weight classes (super welter, middle, super middle) within just ten bouts. Such an accomplishment would be almost unthinkable in the men’s game given the depth of talent. Come to think of it, Lomachenko did it in twelve – but it is extremely rare. I digress…

Like Taylor vs Serrano, Shields vs Marshall was fiercely contested. Perhaps a mite less of the sweet science was on display, but it was an entertaining duel all the same. The Brit motored forward like an old-timey slugger trying to chop the more gifted Shields down, but was mostly out-worked and out-manoeuvred and the self-appointed GWOAT prevailed via unanimous decision.

So, what did I learn from watching both fights? In truth, not a lot. My enjoyment didn’t come as a huge surprise: I expected fast-paced action given the reception both clashes had received. In the end, though, I was not converted into a diehard women’s boxing fan.

At this point, you might be wondering what I meant when I referenced “two different sports” earlier. I’ll do my best to explain.

In men’s boxing, the number of participants is such that becoming a champion confers a kind of exalted status; or it would if there weren’t so many corrupt sanctioning bodies and junk titles. Around the world, there are literally thousands of combatants in each weight category, and reaching the summit means vaulting an imposing series of increasingly challenging hurdles. In England, for example, your first professional title might be a regional belt; followed by a national championship; then a Commonwealth strap; followed by British honors; then a watered-down version of a world title. Eventually, after perhaps 25 or 30 bouts spanning several years, you will receive a shot at glory, a legitimate world challenge.

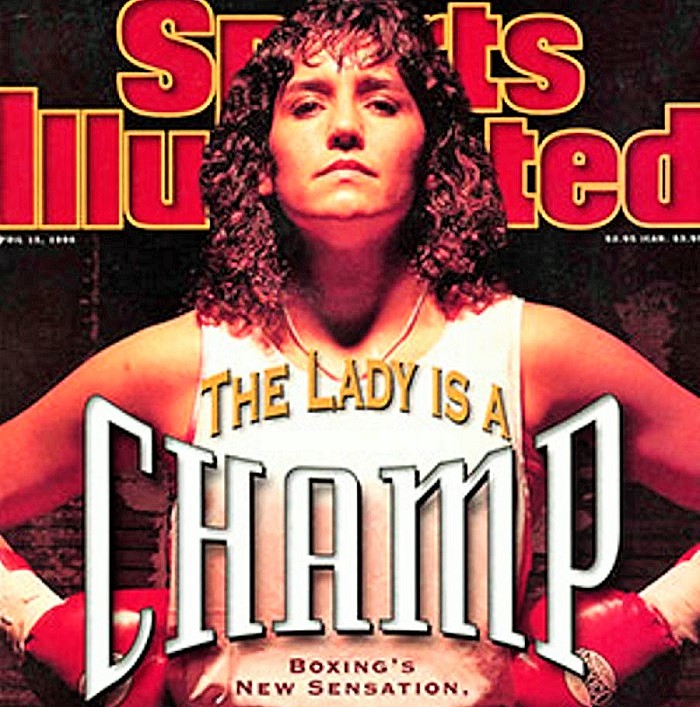

The fact that there is stiff competition in each weight class of men’s boxing is hardly surprising; it stems from the long, storied lineage of the sport dating back hundreds of years. Female boxing, on the other hand, wasn’t really legitimized until Christy “The Coal Miner’s Daughter” Martin started appearing on Don King cards in the early 1990s. Despite Martin’s fan-friendly style, female fisticuffs remained a curious sideshow until the last ten years or so, when the likes of Heather Hardy, Taylor and Shields came to prominence.

All of which is to say that, competitively speaking, men’s boxing is a deep ocean by dint of its visibility through the ages. While female boxing is on the rise, its formerly niche status means there is a far shallower global talent pool: the pathway to success is more direct and less fraught with danger. Naturally, those who take umbrage with my stance won’t be assuaged by such realities. “Okay,” I can hear them sigh. “We already know men’s boxing is more established around the world. But women’s boxing is fresh and exciting and it’s here to stay. What’s your problem?”

One problem I have, if you want to call it that, is I cannot accord the same level of admiration to both male and female champions due to the disparity between their respective levels of competition. (Admittedly, a combination of savvy management and alphabet soup chaos means not all male champs are necessarily elite-level pugilists either.) But in and of itself, that shouldn’t preclude me from regularly watching and enjoying women’s bouts, right? So why don’t I?

Perhaps it’s because female fighters are, generally speaking, slower, less athletic, less powerful, and less exciting than their male counterparts. No hate, just reality: there is a different aesthetic to women’s boxing. Transpose Savannah Marshall’s limited skillset to the men’s game and it’s impossible to imagine her becoming a world champion, much less in her ninth bout. If Shields were a man, would her innate ability really guide her (him?) to titles in three divisions inside just ten fights? I don’t believe so.

All this being said, it’s great to see women’s boxing flourishing. There is obviously a growing appetite for it, the sport is widely covered by the media, and some of the top fighters can command million dollar paydays. Back in April, Katie Taylor and Amanda Serrano drew a crowd of almost twenty thousand to the Mecca of Madison Square Garden, generating close to $1.5 million in ticket sales. This should be celebrated.

Even so, some perspective is needed. Tickets for Taylor vs Serrano were priced more modestly than for a male superfight. In 2017, the UFC drew a similar sized crowd to Madison Square for Conor McGregor vs Eddie Alvarez, but that translated to a live gate of $17.7 million. When Cotto and Margarito fought at the Garden ten years ago, the bout sold fewer tickets (17,943) than Taylor vs Serrano but grossed over three million, double the revenue.

This shouldn’t come as a surprise: the vast majority of fight fans are male, as has always been the case. So it doesn’t seem outlandish to suggest that, whether they realized it or not at the time, part of what attracted men to pugilism in the first place was the fact that, historically, the ring is a masculine domain where male courage is glorified and celebrated. And it seems to me that there’s nothing wrong with that. Watching women trade blows simply isn’t the same experience. It’s different in a whole host of ways.

To be fair, this is a straw man: no one claims female boxers are as adept at fighting as their male counterparts; from a physiological standpoint, how could they be? Nor does anyone claim that female fans outnumber male, or that the female ranks are as oversubscribed or talent-rich as the male. So I guess the real point to stress here is that, as a fan, there is a diluted sense of wonder when watching, say, a multi-weight or undisputed female champion go through their repertoire. The comparative lack of power downgrades the drama. The obvious lack of depth undermines the prestige.

A cursory glance at the female title picture illustrates this point: there are currently undisputed champions in five weight divisions. The four-belt super middleweight queen is Franchon Crews Dezurn, a veteran of just ten bouts; Shields has all the middleweight straps; Jessica McCaskill, with a 12-3 record, holds the aces at welter; Chantelle Cameron rules the roost at super lightweight; and Katie Taylor reigns supreme at lightweight. Even featherweight, super featherweight and super welterweight are virtually monopolized, with Serrano, Alycia Baumgardner and Natasha Jonas holding three out of four belts.

What does such divisional dominance tell us? That the champions are just the best of the best, truly elite, untouchable operators? Or that mopping up all of a division’s hardware is just, well, easier? Hell, a 40-year-old woman who had been a professional fighter for less than a year (Nina Hughes) just won a world title in her fifth bout!

Women’s boxing has come a long way and a lot of people dig it and that’s great. But not everyone has to love it, especially since there are an absurd seventeen weight classes in the men’s game to track and enjoy. And one’s reasons for not loving it can be more nuanced than a belief that females shouldn’t beat seven bells out of each other. Visually, it’s just a different kind of spectacle to the men’s game, the divisions less laced with talent, the punches less impactful, the rounds and bouts shorter, and the whole concept unbacked by centuries of heritage – though acknowledging the latter makes you sound like a bloody royalist!

It’s certainly easy to imagine female boxing becoming more competitive in the years to come, and as it does, it will surely provide more drama. In the meantime, I hope that promoters investing in women’s boxing concentrate on making truly compelling matches, rather than exposing would-be fans to poor-quality contests high up a bill simply to tick a box. That happens way too often at present.

That aside, there’s no doubt that women’s boxing is here to stay and that standard-bearers like Shields and Taylor will inspire the next generation. We will undoubtedly see more female main events and all-female cards going forward, and in a decade or so, a more competitive landscape will emerge. By that time, professing apathy to women’s boxing won’t just induce your excommunication from the right-thinking ranks; it’ll bring down the guillotine. —Ronnie McCluskey