When Fighters Fought

Speaking for fans of a certain vintage, we all have a special set of boxers, the ones that forged our love for the sport, the ones on those old VHS tapes and faded magazines we can’t let go or give away. Wind the clock back a couple of decades to the 1990s, and you will find my favourite era. And while it’s fair to say the 90s are not generally considered a Golden Age for boxing, with the benefit of hindsight, they look pretty damn good from where I’m standing today.

The heavyweight division of the 90’s took us on a crazy, roller coaster ride with the brilliant ensemble of Tyson, Holyfield, Bowe and Lewis, it all culminating in an undisputed champion before the decade closed out. The middle and super middleweight divisions produced some of the most memorable talents and fiercest rivalries as Hopkins, McCallum, Toney and Roy Jones Jr. ruled stateside and Watson, Benn, Eubank and Collins dueled for supremacy on my side of the pond. Down at featherweight, Prince Nassem was blazing a trail with his theatrics and dynamite power, bringing unprecedented purses to the lower weight classes. But the cream of the crop for the 90s was surely the welterweights.

And if you happen to think the welterweights of recent years are a stacked bunch, consider that The Ring’s 1997 annual ratings featured this mouth-watering top four: Oscar De La Hoya, Pernell Whitaker, Felix Trinidad, and Ike Quartey. Such was the pedigree of this quartet that they also comprised three of the top four spots on the pound-for-pound list, along with Roy Jones Jr., with the fourth-rated welter, Ike Quartey, still making the cut. Looking back, it’s an outstanding line-up for a single division, and it led to a series of cracking matches, which could serve as inspiration for the welterweights of today who, by comparison, appear to be collectively seized-up like an old, rusty engine block.

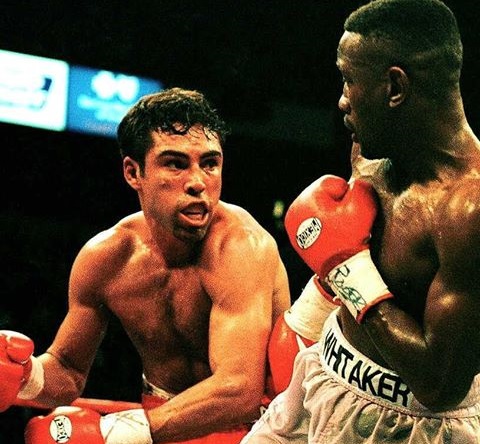

By 1998, boxing’s “Golden Boy,” Oscar De La Hoya, was already a four-weight world champion, having stepped up to dethrone long-reigning WBC king, Pernell “Sweet Pea” Whitaker by razor-close decision the year before. He also had the looks to crossover into a hitherto untapped boxing market of screaming teenage fan-girls, and with the help of promoter Bob Arum, the Latino heartthrob with the sweet smile and an even sweeter left hook worked wonders at the box office.

Whitaker, a four-division champion himself and the former pound-for-pound number one, was a decade removed from his first world title fight, and at 34, clearly past his prime. Even so, the defensive maestro had the skills to give almost anyone nightmares, and in fact, many had thought he deserved better against Oscar.

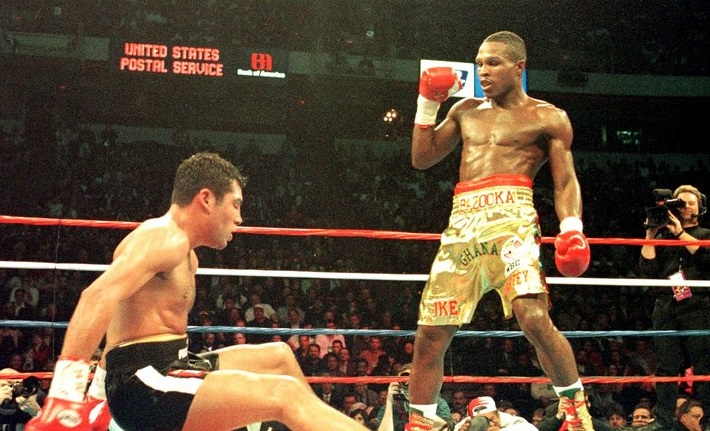

Then there was Puerto Rican assassin, Felix “Tito” Trinidad, and Ghanaian dangerman, Ike “Bazooka” Quartey. WBA champ since 1994, Quartey was coming off a hard-fought majority draw against another top contender, Jose Luis Lopez. Fighting through illness, the African suffered two knockdowns, but dominated enough behind his ramrod jab to retain his title, landing 313 left leads over twelve rounds, a CompuBox record that stands to this day. In contrast to Quartey’s more measured but solid boxing style, Trinidad was a pure puncher of the highest calibre. Twenty-eight of his thirty-two victims going into 1998 had been stopped, with only Hector Camacho lasting the distance during Tito’s run of twelve straight title wins.

So, what happened next? Simple: they fought each other. Sure, it took a few months to put together, and there were some inevitable road bumps along the way, but by February 1999 we got two superb match-ups between the four of them in the space of a week.

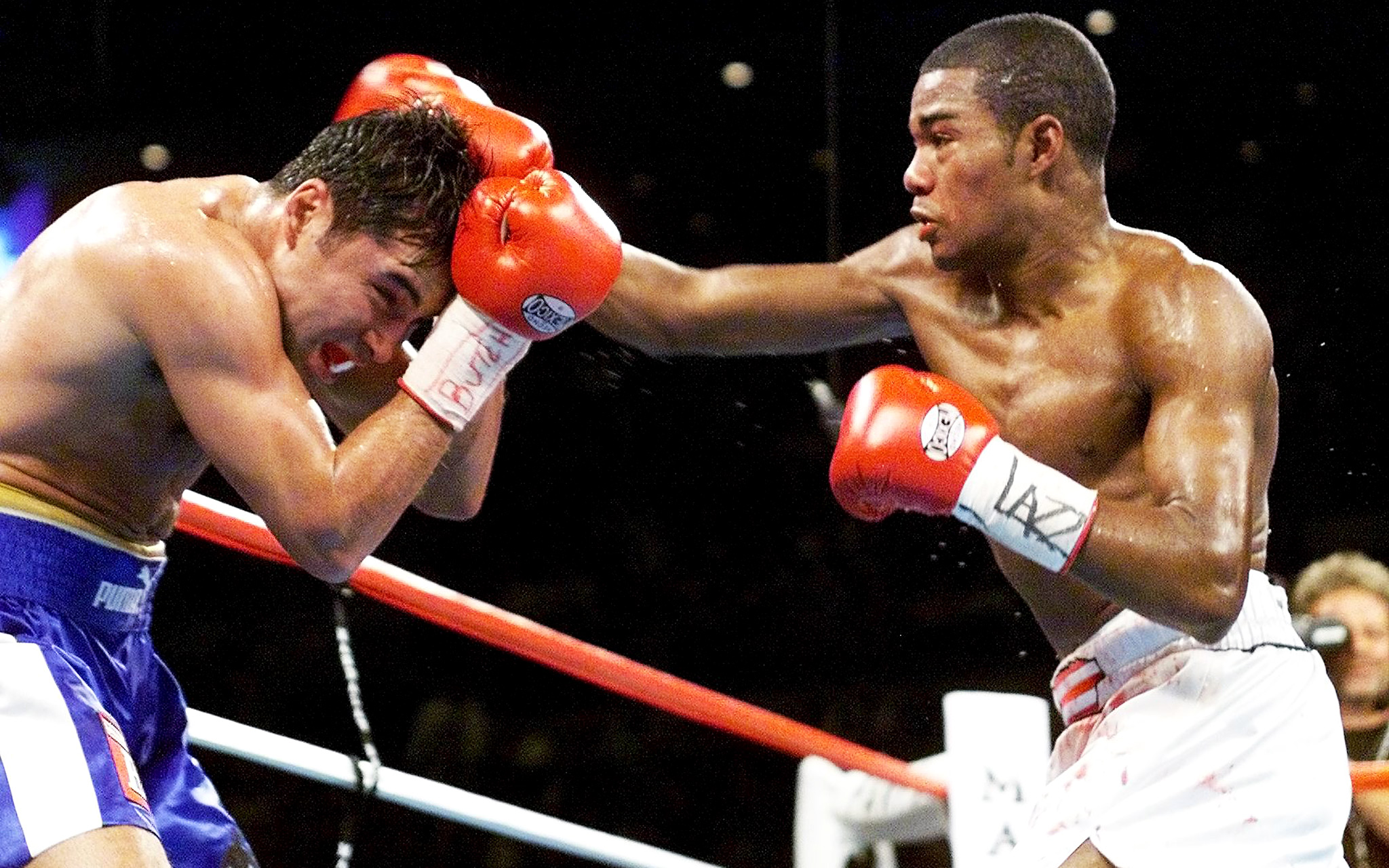

First up, De La Hoya, who’d squeezed in five title defences since dethroning Whitaker, took on Quartey, who hadn’t fought for 18 months and had been stripped of his WBA belt. It was considered easily “The Golden Boy’s” most dangerous assignment to date, and so it proved to be. They exchanged knockdowns in an explosive sixth round, and when the action slowed it was the Ghanaian who appeared to edge ahead. But De La Hoya proved there was real fighting mettle underneath the pop-star persona, tearing out in the final round and sending Quartey to the canvas before unloading the kitchen sink in an effort to score a last-gasp stoppage. Somehow Quartey fought back from the brink and survived the onslaught, though ultimately lost the match by split decision.

In the second unofficial “semi-final” bout, former champ Whitaker challenged Trinidad, but sadly for Sweet Pea fans, the bout confirmed that his days alongside boxing’s pound-for-pound elite were all but finished. Returning after a sixteen month layoff following two positive tests for cocaine use, the American was beaten widely on points, though the fact that a faded, rehab-version of Sweet Pea could compete with a peak Tito Trinidad is really a testament to his amazing talent. Who knows what the result might have been just a year or two earlier? Whitaker was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2007 and is still remembered as arguably the best boxer of the 1990s.

And so, with two of the original quartet left standing, and after some financial wrangling between rival promoters Bob Arum and Don King, the stage was set for a mega-fight between Oscar and Tito. Billed as “The Battle of the Millennium,” it was the most highly anticipated welterweight showdown since “Sugar” Ray Leonard and Tommy “Hitman” Hearns, almost 20 years earlier. The two undefeated champs entered the ring with 34 world title wins between them, in a fascinating clash between Mexican-American and Puerto Rican boxing icons. It became the richest non-heavyweight event in history, generating over $70 million in pay-per-view revenue.

Unfortunately, the fight itself never caught fire. De La Hoya boxed his way to an early lead, but then back-pedalled through the later rounds only to find himself on the losing end of a controversial decision. The real lesson to be drawn for today’s welterweights though is not about the anti-climactic battle in the ring; rather it’s the story of how, by signing to fight each other in the first place, four top welterweights chased greatness and those bouts in turn sparked another sequence of terrific match-ups over the ensuing years, involving some of the best fighters of modern times. It went something like this:

Quartey moved to 154 but lost to a new young champion, “Ferocious” Fernando Vargas, and disappeared into early retirement. Vargas scored excellent wins over Winky Wright and Quartey, but was then stopped in an epic, six-knockdown shootout with Felix Trinidad. After unifying against De La Hoya at 147 and Vargas at 154, Trinidad blitzed his way to another belt at middleweight before the Tito express was finally halted in its tracks by Bernard Hopkins.

Meanwhile, De La Hoya lost to rising lightweight “Sugar” Shane Mosley in an absolutely scintillating twelve round battle, before going on to defeat bitter enemy Fernando Vargas at 154 and then claiming another title at 160. He then stepped up to face the most daunting challenge of his career in long-time middleweight king Bernard Hopkins who stopped Oscar via devastating liver shot in round nine.

With his brilliant victory over De La Hoya, Mosley had been proclaimed the new pound-for-pound star, until Vernon Forrest came along to hand Mosley back-to-back losses. Forrest was then promptly knocked out by Nicaraguan wild man Ricardo Mayorga, who subsequently moved up in weight and was knocked out first by Trinidad, then De La Hoya, and later Mosley, although “El Matador” did salvage a late-career win over Vargas. Meanwhile Mosley had moved up to 154 after losing to Forrest, beat De La Hoya a second time, but then lost a unification fight with Winky Wright, before scoring knockouts of Vargas and Mayorga.

Winky Wright, who’d earlier lost to an undefeated Vargas, finally got his just dues after beating Mosley twice and then giving Trinidad a boxing lesson, before losing to the scourge of the bunch, Hopkins. Quartey even made a comeback five years after losing to Vargas, scoring three wins before dropping a controversial decision to Vernon Forrest and finally calling it a day after losing again to Winky Wright. Forrest also claimed another title at 154 pounds after beating Quartey, but was tragically murdered while still champion, in 2009.

All in all, including the original welterweight quartet plus the fights that branched off from them involving Mosley, Forrest, Mayorga, Vargas, Wright and Hopkins, there were a total of 28 bouts over a period of eighteen years, beginning with De La Hoya vs Whitaker in April 1997 and ending when Mosley and Mayorga, long over the hill, fought for a second time in August 2015. Whether today’s welterweight division could ever spawn a similarly memorable string of tilts remains to be seen, but at the moment things don’t look promising. Still, the formula is simple: make the best fights.

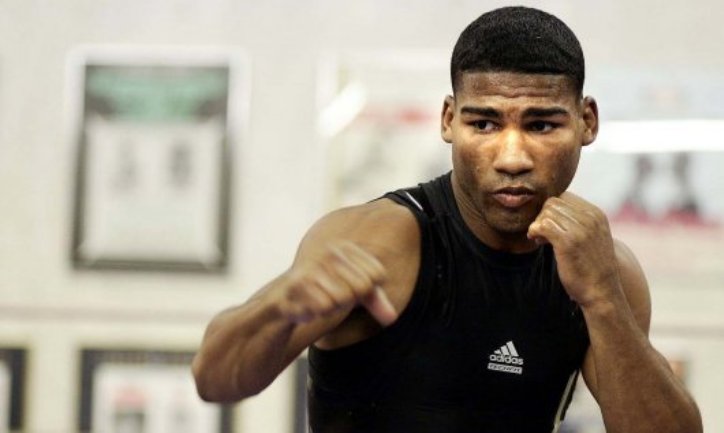

There’s certainly no shortage of matches to be made. And while the dream fight everyone has been talking about for the last several years, Errol Spence Jr. vs Terence Crawford, remains elusive, if not impossible, it’s still a marquee clash that would go a long way towards revitalizing the fight game. In fact, any combination involving those two and Yordenis Ugas, Vergil Ortiz Jr. or Jaron Ennis is a more than solid match-up, while bigger sharks like Tim Tszyu, Jermell Charlo or Brian Castano are circling at 154 pounds.

Yes, at this point, all of that seems very unlikely as so many of these top talents appear content to step through the ropes once or twice a year and while the competing promoters avoid each other, but the point is that if the sport can just start making some of the best matches, who knows what they could lead to. Once the dominos start to fall, and the fights start getting made, and the boxers finally wake up to the fact that the clock is ticking on their respective careers, we might just luck out and get some great battles and rivalries to remember in the years to come. And just maybe, one day twenty years from now, someone will be inspired to pick up a keyboard and reminisce fondly about how their favourite series of welterweight fights once kicked off. Though they won’t have them saved on a dusty VHS collection in the loft. — Matthew O’Brien