Adios, Dinamita

Greatness has a soft spot for grit.

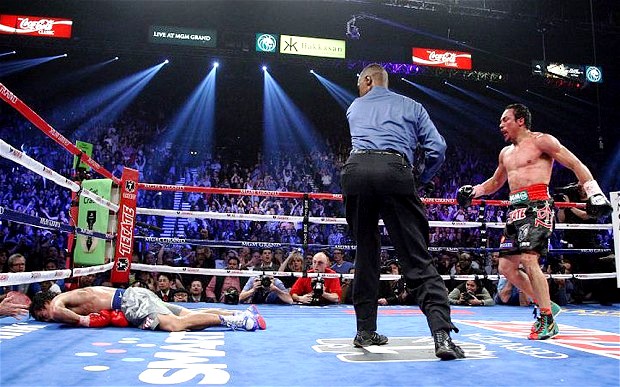

In the ring, Juan Manuel Marquez had grit in spades. He showed it practically every time he stepped between the ropes. Several opponents–some of whom one would’ve thought had no business doing it–were able to send him to the canvas, from whence Juan Manuel would invariably get up, more determined than before to prove himself the better fighter. One of those opponents, a Filipino whom he faced in four fights, knocked him down a total of five times–thrice alone in the first round they ever fought. The last round they fought, however, found that same Asian fighter knocked unconscious on the canvas, while the fighter they called Dinamita celebrated across the ring, blood flowing freely from his shattered nose. Some would call that grit.

Outside the ring, “Dinamita” traveled a path all his own; he voiced his opinions loudly and clearly, and ultimately did anything that could conceivably help him win. He switched allegiances to pursue the fights he wanted. He trained like a man possessed, at altitudes where mere mortals would have trouble climbing a single flight of stairs. He flipped the finger at promoters when he felt their offers weren’t good enough. There was that time when, against his trainer’s advice, he jumped two weight classes to face the best fighter pound-for-pound in the world. He once gave an interview on live TV while buck-naked except for the sombrero covering his genitals. He even went through a urine-drinking phase; he thought it would help nourish his body and make him a stronger fighter. Some would call that weird, but some would call it grit.

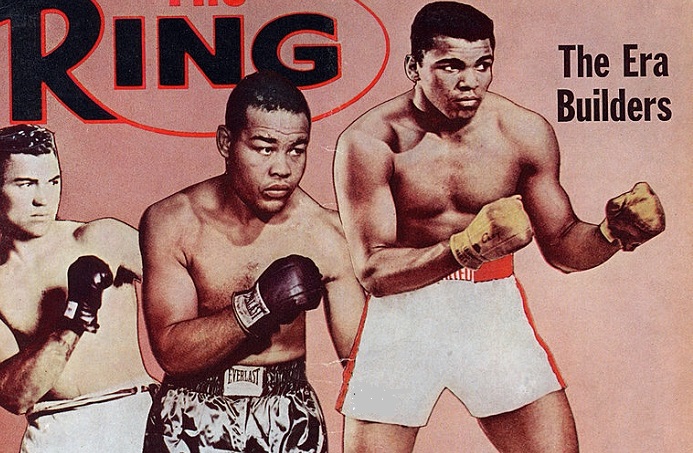

His accomplishments speak for themselves, and ensure for him a first-ballot entry into boxing’s Hall of Fame. A nine-time world champion across four different divisions. A participant in two official Fight of the Years, and several other high-ranking candidates. A scorer of one of the most violent one-punch knockouts of all time. A top-five all-time Mexican fighter. The names on his ledger read like a who’s who of his era at the lower weight classes: Manny Pacquiao, Floyd Mayweather Jr., Marco Antonio Barrera, Timothy Bradley, Joel Casamayor, Juan Diaz, Michael Katsidis, Chris John, Orlando Salido.

But it took a while for Marquez to hit the big leagues. In the beginning, Juan Manuel’s style wasn’t crowd-pleasing, and was in fact anathema to his Mexican heritage. Where his countrymen were seen as fearless warriors, willing to take three shots to land one, Juan Manuel stuck to a slow-paced counter-punching style that was averse to absorbing damage. Making the opponent miss was as important as making him pay for it. If the audience and the judges failed to appreciate his mastery, it was their loss.

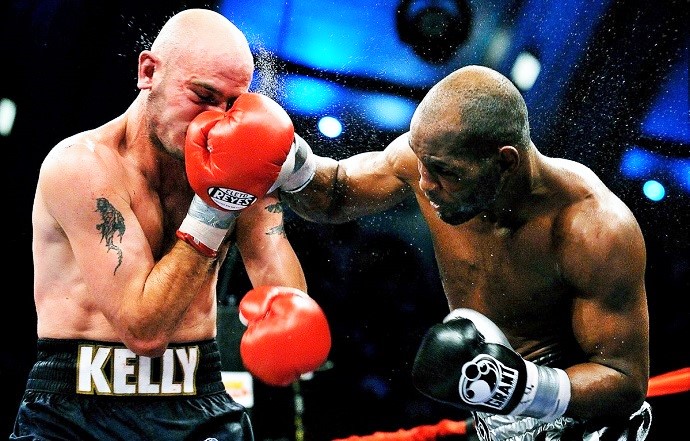

Until, that is, it became clear that such a style wouldn’t get him as far as he wanted to go. So Juan Manuel started adding violence to his professorial performances. Not only did he allow himself to open fire more often, but now, when tagged with a hard punch, Juan Manuel was less and less willing to let it slide. The fact that someone landed a glove on the proud tactician stung way more than the physical impact of the punch itself. And that’s when the combinations really started flying, propelling his fights to new dramatic heights, with Juan Manuel linking increasing numbers of punches together, like a baroque composer riffing on his main theme.

He would throw a stiff jab, and follow it up with a right, then fire off a left hook, mix a clean uppercut in there somewhere, and then, just when you thought the combination was over, he’d fire off his trademark hook to the body, the signature punch of so many Mexican greats. Some fighters couldn’t even pull off those combos convincingly on the mitts, much less employ them in combat. But Juan Manuel did, and by the end, his opponents were so confused and hurting so much that they weren’t able to see where the punches were coming from anymore. Unsurprisingly, it was at this point that Juan Manuel and the Mexican audience finally started bonding.

“Dinamita” forged his newly-found style in close collaboration with Nacho Beristain, his legendary trainer, the one who guided Juan Manuel’s career from beginning to end. It amalgamated all the teachings of one of the last true boxing gurus with the Mexican grit displayed by the greatest Aztec fighters of all time. Beristain has coached more world champions than he can remember at this point: Daniel Zaragoza, Ricardo “Finito” Lopez, Humberto “Chiquita” Gonzalez, Gilberto Roman, and even Juan Manuel’s brother, Rafael, to name a few. But there’s no doubt in anyone’s mind, not even Beristain’s, as to who his masterpiece is.

It was under that style that Juan Manuel’s name came to be known around the world, giving hell to many of the best fighters of his generation. And if their organs were scrambled and their brains rattled along the way, there is no doubt his opponents became better fighters for having faced Juan Manuel. For to face Dinamita was to take a crash course in The Sweet Science at the highest level, an opportunity to appreciate up close just how much can be accomplished with nothing but a couple of fists, all while learning the limitations of your own game. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of any Juan Manuel Marquez fight was that he was at a clear disadvantage in many of them: he was seldom the younger fighter, or the stronger one, or the faster one, or the one who punched harder. But he was almost always the smartest one in there, and it was a spectacle in itself to witness the imposition of brain over matter that a Marquez victory represented.

Meanwhile, those seven defeats he accrued over sixty-four fights were in no way his fault–or so he would emphasize to anyone within hearing distance. The judges, the referee, boxing politics, or the economics of the game–there was always something out there conspiring against him. After all, it had never been easy for Juan Manuel to get the recognition, the opponents, or the paychecks his talents commanded. Why would things be any different once he hit the big time? He wasn’t the first fighter, and he won’t be the last, to embrace the underdog mentality to achieve his ends, but it certainly made him a much more interesting character than if he had been the matinee idol who offers nothing but platitudes.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NSn3wWoKz-k

And it’s not like Juan Manuel’s career was without controversy. In pursuing his legacy in general, and a much desired victory over the Filipino in particular, Juan Manuel came to associate with dodgy characters well-known in boxing circles for their knowledge of chemical concoctions. The collaboration allowed him to sculpt his formerly lean featherweight body into that of a chiseled welterweight. It also helped prolong his career at a time when most fighters are already out of the game. Accusations flew for a while, especially in the aftermath of the biggest win of his career, when he refused to submit to stringent drug testing. However, as usual, nothing could be proved, and whether “Dinamita” used illegal methods to carve the muscled body that helped him vanquish his nemesis will remain the single most important question regarding his career.

What can never be questioned, though, is the grit and will to win of this modern great. In Juan Manuel Marquez a seldom seen mix of ring intelligence and determination produced a combination puncher of rare quality, not likely to be replicated any time soon. His discipline, focus, and talent propelled him to the upper echelons of the sport, while fending off challenges from fellow greats, younger lions, grizzled veterans and everyone in between. With his tremendous displays of courage, poise, and skill, Juan Manuel reminded us time and again that just as boxing remains the hardest athletic pursuit known to man, it also produces the most incomparable, downright beautiful choreographies in all of sports.

Enjoy your retirement, champ. You’ve certainly earned it.

–Rafael Garcia