Bradley vs Marquez: Something’s rotten in Vegas

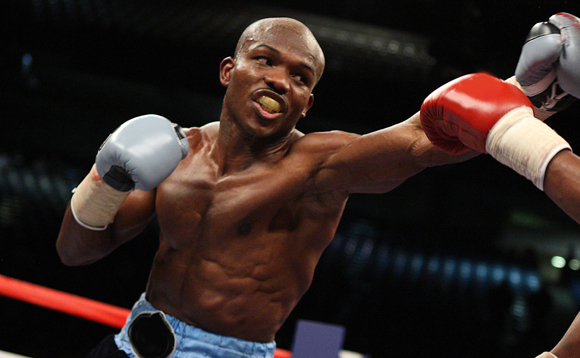

In his first match since knocking out Manny Pacquiao last December, Juan Manuel Marquez will return to the ring on October 12 against WBO welterweight champion Timothy Bradley, seeking to win a world title in a fifth weight division, a feat no other Mexican fighter has achieved. “Desert Storm”, for his part, is coming off a barn-burner against Ruslan Provodnikov last March, when he survived the Russian’s fearsome onslaught to edge him via points. But despite all the caché and intrigue associated with such a five-star confrontation, Bradley vs Marquez is unfortunately making waves in the boxing world for all the wrong reasons.

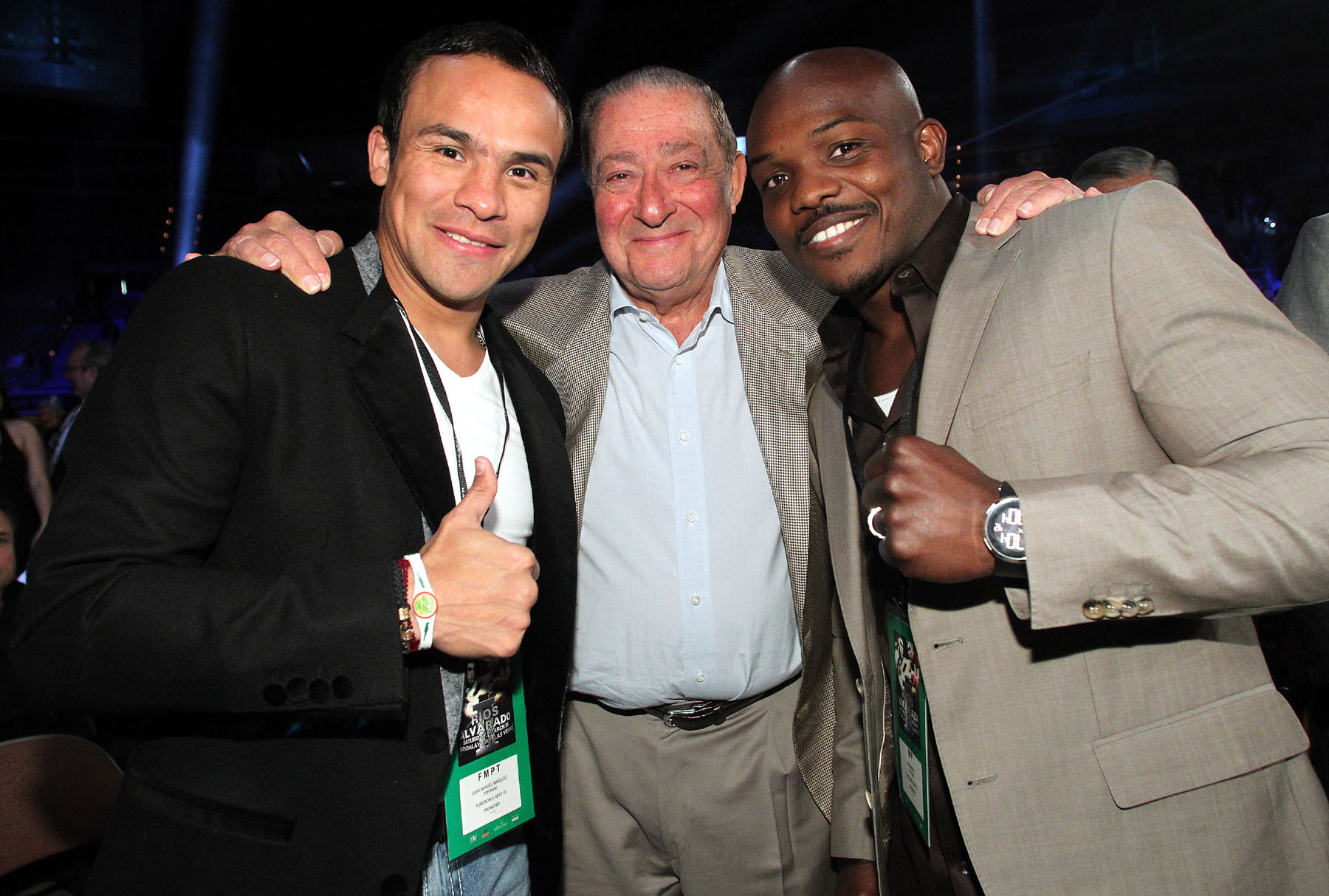

It all began when Bradley—still battling the phantom of the bogus decision earned against the Pacman last year—signed to fight the great Marquez under the condition that random drug testing be conducted for both boxers. After his last performance Marquez was haunted by a phantom of a different sort, as many suspected his startling one-punch knockout of the Pacman was a product of not entirely legal training methods. Therefore, he duly obliged to Bradley’s request. Bob Arum, serving as promoter to both fighters, sealed the deal and assured the participants and the media that strict drug testing would be enforced.

Two months before the opening bell, however, something smells rotten. A few days ago, Bradley threatened to withdraw from the Marquez fight after it became public that the responsibility of enforcing the drug testing protocol would fall to the Nevada State Athletic Commission (NSAC). Bradley claimed this contradicted the contract he signed, which said that either USADA or VADA would perform the drug testing. Arum, looking to appease all parties, tried to sell people on the idea that it doesn’t really matter whether the process is carried out by the NSAC, USADA or VADA, since they’re all pretty much the same. In other words, a blood test is a blood test is a blood test, said Uncle Bob.

This is clearly bullshit, since there exists an obvious conflict of interest in having the NSAC perform drug testing on the participants of such a big fight, as a positive test could result in a cancellation, denying the NSAC of large sums of money in the form of sanctioning fees. The NSAC wouldn’t want to make public a positive test any more than Arum or the guilty party. USADA and VADA, on the other hand, have no such vested interests. Further, it is well documented that USADA’s and VADA’s processes are much more effective than what passes for drug testing at state athletic commissions in terms of protocol and of substances tested for.

And so boxing once again confronts the the 300-pound gorilla we call Performance Enhancing Drugs (PEDs), as the issue has become part and parcel of every conversation associated with Bradley vs Marquez. The Mexican’s reputation continues to be afflicted by the same accusations that marred his victory over Pacquiao last year. Fans have also been turned off by Marquez’ lack of effort in facing up to the issue: he has kept mum on whether the contract was explicit regarding the kind of drug testing to be performed. And when Bradley threatened to balk on the grounds that the testing protocol in place wasn’t good enough, Marquez only came back with a counteroffer: “Dinamita” would agree to whatever testing Bradley requested only if “Desert Storm” submitted to a rehydration clause restricting his weight on fight night.

The rehydration clause was never part of the original contract. Marquez only brought it up when Bradley began to question the validity of the NSAC’s drug testing methods. However, “Desert Storm” has by now reluctantly agreed to climb into the ring, as he commented recently that:

“I chose to do whatever the commission wanted to do, because I wanted to be licensed to fight in Vegas and if I didn’t abide by their rules then I wouldn’t get licensed in Vegas to fight.”

Despite all this, Bradley plans to adhere to self-imposed drug testing with VADA, but Marquez isn’t likely to follow his lead any time soon. Draw your own conclusions.

Thus, Arum and the NSAC have effectively blackmailed Bradley: he will shut up and fight, or he will forego the chance of participating in future events in the gambling and boxing mecca of Sin City.

And a good deal it is for Top Rank to salvage Bradley vs Marquez, as it currently holds the losing hand in the frigid standoff with promotional rival Golden Boy. Under these circumstances, Top Rank has been forced to spread its net far and wide in trying to generate revenue. Lacking an abundance of big names to stage major events in North America, it has bet heavily on a push to open the Asian market to boxing.

To this end Top Rank signed two-time Olympic gold medalist Zou Shiming, who will perform on the undercard of Pacquiao’s comeback fight against Brandon Rios in Macau, China, the very country that an article recently shared by VADA identified as a “major pipeline to the US for PEDs and PED precursors”.

The question of why athletes cheat has a very simple and understandable answer: to either catch up with, or gain an edge over, the opponent. However, the question of why the agents who supposedly oversee adherence to the rules fail at their jobs is a bit more complex. Game theorists, nonetheless, have come up with a fresh perspective on the issue, as reported by The Economist:

“…The inspector has several reasons to skimp on testing. One is the cost. Another is the disruption it causes to the already complicated lives of the athletes. A third, though, is fear of how [sports fans] would react if more thorough testing did reveal near-universal cheating, which anecdotal evidence suggests that in some sports it might. Better to test sparingly, and expose from time to time what is apparently the odd bad apple, rather than do the job thoroughly and find the whole barrel is spoiled and your sport has suddenly vanished in a hailstorm of disqualifications.”

Indeed, even casual fans of the sweet science will agree that PEDs usage in boxing is probably more widespread than we are led to believe. But usage per se is not the real issue. The real question is how to guarantee a level playing field and ensure fair contests. The fact that some boxers use PEDs and others don’t, and that some are caught cheating while others get away with it, makes a mockery of the concept of fair competition itself, destroying the romantic notion of boxing which draws fans to the sport in the first place. If boxing is less about the purity of face-to-face, one-on-one battles and the testing of individual skill, will and courage, and instead becomes more about whose resident chemist concocts the best PED recipes, then the matches are fraudulent and pointless and the sport has lost all integrity.

–Rafael Garcia