The Golden Door

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!

The last lines of the sonnet ‘New Colossus’, by Emma Lazarus, were etched on the base of the Statue of Liberty, and thus became a part of American history. They are an ode to the downtrodden and a welcoming to those seeking a better life; an invitation to thrive in a new land. The words will forever be associated with American history, but they could very well be regarded as an axiom for the sport of boxing.

Throughout its long and storied history, boxing has been a means of escape, an escape from poverty and racism, and a chance at a new life for the tired, the poor and the tempest-tossed. When all hope is seemingly lost, salvation can come in the strangest of forms.

Prizefighting is a term not often used today, but its meaning still rings true almost 150 years after the Marquis of Queensberry devised the rules which govern the sport. For many, it’s more than the thrill of victory or testing one’s courage and strength that lures them to the ring; it’s the prize. Sometimes that prize is one that ultimately transforms one’s life and inspires one’s people.

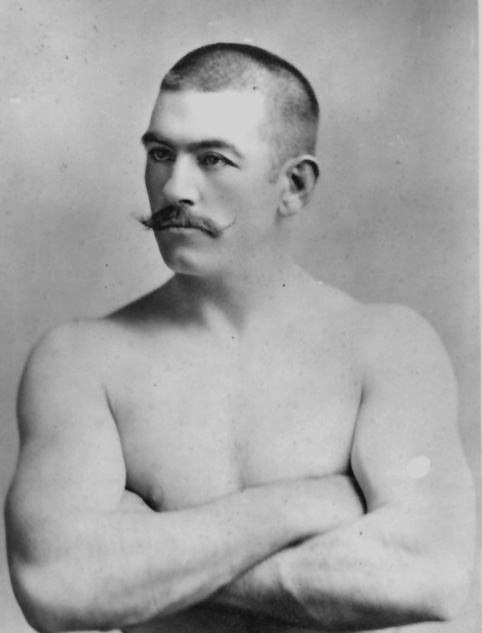

As the son of Irish immigrants, John L. Sullivan went from lowly beginnings to the most famous man in all of America. As the first universally recognized heavyweight champion of the gloved era, Sullivan epitomized the rise of America’s Irish immigrants. Christopher Klein, Author of Strong Boy: The Life and Times of John L. Sullivan, puts Sullivan’s rise to the top into perspective:

“Sullivan’s symbolic position as the world’s most powerful man transformed him into the first Irish-American hero. To a generation of immigrants who had believed themselves powerless under the thumb of the British in their homeland, slighted in their new country, and traumatized by the horrific famine, Sullivan’s strength and self-confidence were an elixir for their malignant shame.”

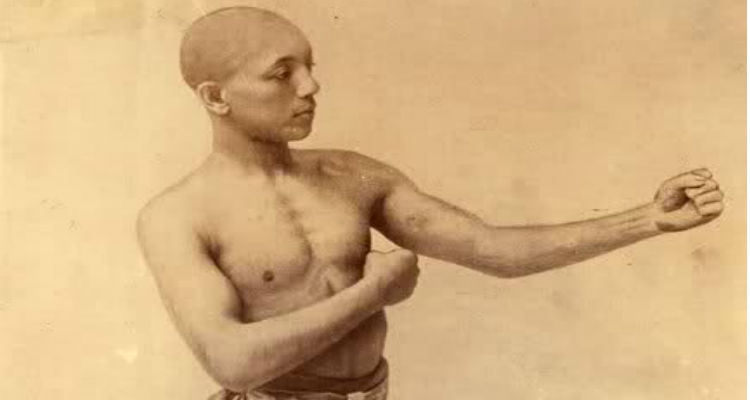

The Irish immigrants to America may have been a downtrodden lot, but their situation paled in comparison to the plight of African-Americans, and it was left to boxing to become one of the few saviors for young black men in the early twentieth century. With segregation, hatred and violence an everyday facet of their lives, it was boxing which afforded a black man a kind of freedom. It was often a begrudging and hateful allowance from bigoted whites, but even so, pugilism rendered so many opportunities that were often thought of as taboo for African Americans.

Boxing broke through cultural barriers; nowhere else could a black man be considered the equal, or even the better of a white man, than in the boxing ring. And nowhere in modern society could a black man act as a free man unless he was a champion fighter.

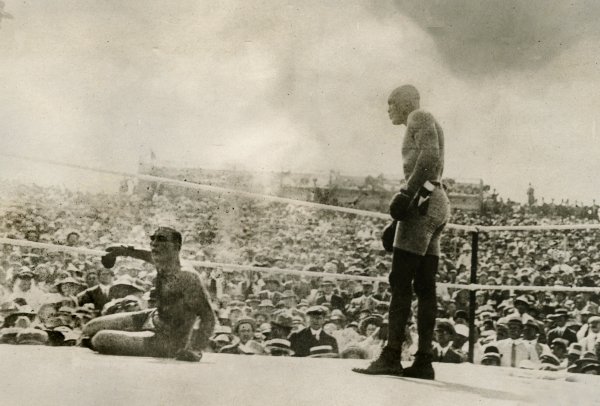

The path to glory was always much rougher for the pioneers of African-American sports. The color line was real and drawn all too often. When Jack Johnson won the heavyweight title in 1908, in Sydney, Australia, he became the first black man to do so and in his newly found position of power, Johnson wasted little time before he took full advantage, taunting and antagonizing his white counterparts.

Johnson drew the ire of whites everywhere. From his position as the heavyweight king he flaunted his wealth and physical dominance everywhere he went. He beat white challengers with ease in the ring and did so while grinning at white crowds and belittling his opponents for their inferiority. Boxing gave Johnson that power and license, and by God he used it, every chance he got. If not for boxing, Johnson could never have carried himself as he did in white American society.

Champions like George ‘Little Chocolate’ Dixon and the ‘Old Master’ Joe Gans, who came before, were also black and boxing undoubtedly improved their lot in life. Unfortunately, more often than not, the establishment turned a blind eye to their accomplishments, as they weren’t perceived as a great threat to the white hierarchy. Johnson, however, was a different matter entirely. Noted writer Jack Slack, of Fightland, explains why Gans and Dixon’s title wins had far less impact on the white hierarchy than Johnson’s: “The heavyweight title was considered the pinnacle of manly achievement. It was absolute. The absolute best fighter in the world was white, and that was what mattered. When Johnson won it, it bestowed the title of ‘His Fistic Majesty’ (as they used to call Sullivan) on a fighter from an inferior race.”

The role of African Americans in the boxing landscape cannot be understated, and boxing in return has given many a young African American boy a chance to escape a life of oppression and despair.

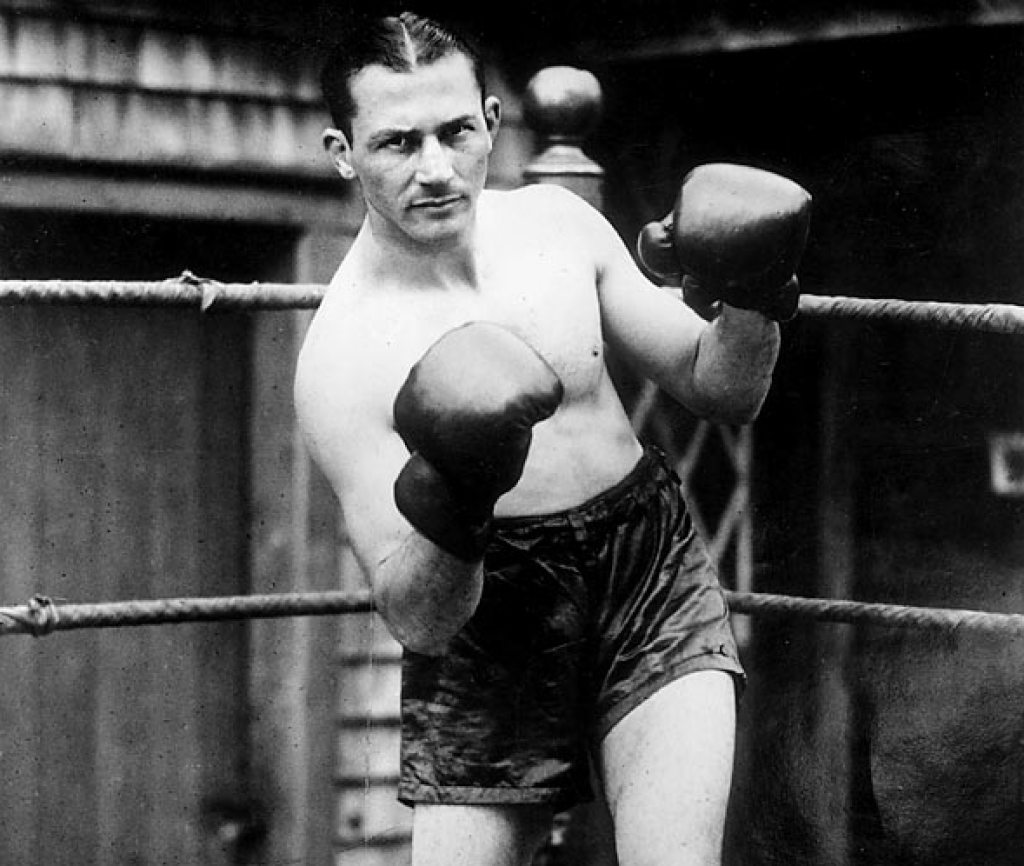

Another batch of new colossi in boxing emerged in the 1920’s when an influx of Jewish fighters arrived on the scene. Poverty, as always, was the precursor to many a boxing career and so it was with the great Jewish champions. The 1920s and 30s saw many great Jewish fighters of note, such as Benny Leonard, Barney Ross and Maxie Rosenbloom, to name but a few. More than any other, it was Leonard who was the flag bearer for Jewish pride in a time when so many Jews were burdened by poverty in ghettos across America.

As legendary boxing writer Budd Schulberg described it in his book Ringside: A Treasury of Boxing Reportage: “In the early decades of the twentieth century, ambitious young Jews were struggling to break out of the cycle of poverty in which so many saw their parents hopelessly trapped. They became songwriters like Irving Berlin and Buddy Rose, budding movie moguls like Zukor and Sam Goldfish (later Goldwyn), furriers and jewelers, and, most notably for me, stellar champions of the prize ring like Joe Choynski, Abe Attell, and my favourite, ‘The Great Benny Leonard’.”

In more recent decades, boxing saw a huge influx of Hispanic fighters. From Mexico to Argentina, Puerto Rico to Nicaragua, young men with such names as Gavilan, Escobar, Chavez, Arguello and Duran dreamed of becoming champions. For some it was respect and prestige that they yearned for, but for most the prize was escape from the injustices of their homelands. There’s a longing to provide a better life for one’s family and once again boxing is on hand to provide opportunities seldom seen elsewhere.

It doesn’t stop with Latin America, though. The old Soviet bloc has produced some amazing talent in recent years, champions such as Sergey Kovalev, Murat Gassiev and Dmitry Bivol, among others. The current middleweight king, Gennady Golovkin of Kazakhstan, is driven by similar ambitions as those who have gone before. Chris Mannix of Sports Illustrated brought to light the bleak reality of Golovkin’s losing two brothers in the Russian Army with no explanation as to how they died:

“In 1990, Vadim died, killed in action. There was no explanation from the government official who called the house, no details. The army there didn’t work like that. He was just gone. Golovkin remembers his parent’s tears. He remembers the empty feeling in his stomach. He remembers a funeral without a body. Serving in the army was dangerous, Golovkin knew that. But he never expected this. The second call in ’94 was worse. Sergey was gone, too. Back came the tears, back came the wails, back came the sinking, empty feeling, multiplied exponentially.”

Perhaps Golovkin’s viciousness in the ring comes from a need to transcend such suffering and grief, and indeed in boxing he has found stardom and a new life full of comforts he could only have dreamed of years ago. And indeed, through the decades since the modern game was established, this is what boxing has meant for so many: giving the hopeless hope, giving the best and strongest a chance to escape the pain and hardship of the past.

Amongst the poverty stricken, the oppressed and the despair-ridden of the world, there are those who possess the courage and determination to struggle for a better life. Boxing, once called “the sport of kings,” gives the strongest and most determined among them the chance, “the golden door,” to pursue such dreams. — Daniel Attias

Perhaps it could go unmentioned, but in the mid-20th century there was one black boxer who exemplified rising from poverty to success and glory: Muhammad Ali. Although his in-ring work was more masterful than his speeches about societal issues of the time, he was important worldwide as a black athlete. His impact in this sense could be the focus of articles like this, but at least he deserves a mention.

No doubt Ali deserved a mention, as did the plethora of Italian-American fighters who came to prominence in the 1940’s and ’50’s. I guess for the sake of not wanting this to be a long, expansive list of every fighter who has escaped hardships thanks to boxing, I couldn’t add them all. This makes them no less worthy though.