Beyond The Sky

For Brin-Jonathan Butler

I didn’t have ten dollars to spend on event parking, so I drove up and parked on the hill below Maine Medical Center. Then I started walking down to the Portland Expo. Outside a corner store, I was stopped by a man holding a cane and wearing a thick winter jacket and what appeared to be safety glasses. He asked me if I had any spare change.

“Things keep getting more expensive,” he explained as he counted what he already had.

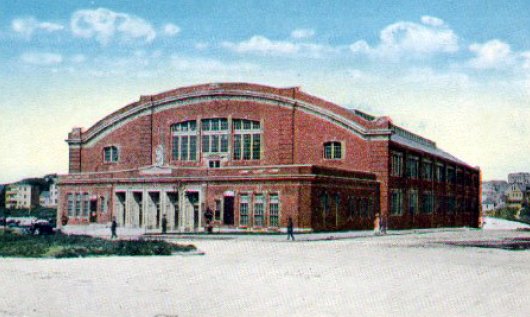

I searched my pockets and placed what coins I found in his palm. He thanked me and stepped back to the curb, allowing me to move along. As I turned onto the next cross street, I saw the Expo, an unremarkable brick building that looks like it could serve any number of municipal functions. Mainers know the building as home to The Red Claws, our minor league basketball team. But I wasn’t there to watch The Red Claws play. I was there to see some boxing.

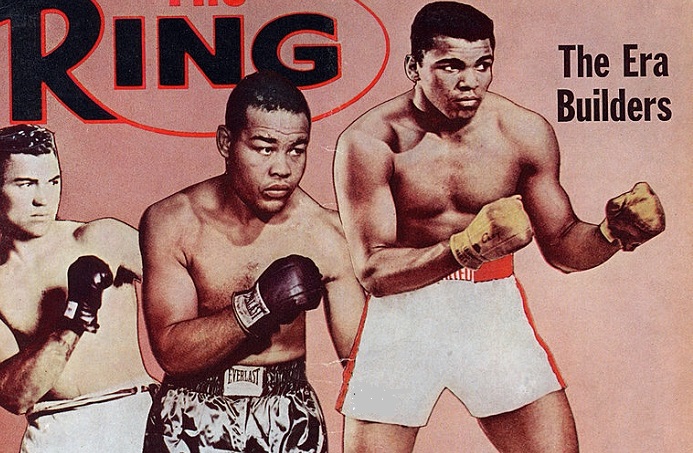

Maine was once home to some major fight cards, most notably the infamous rematch between Muhammad Ali and Sonny Liston that took place in Lewiston. Now the only boxing at the Expo is an annual November event promoted by the Portland Boxing Club, a nonprofit organization. The head coach, Bob Russo, is a Maine legend. In his youth he served as a glove boy for fights at the Expo and his uncle had been chairman of the Maine Boxing Commission. As a coach, he is known for his work with amateur boxers who, collectively, have won over two hundred championships in the past twenty-five years.

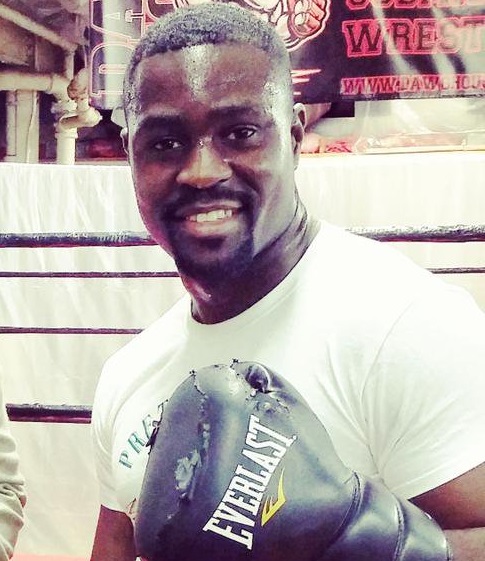

Russo does have a small stable of pro fighters which includes Russell Lamour and Jason Quirk, both of whom were appearing in separate bouts that evening. Of the two, Lamour has received more media attention. At the time of the Expo event, he was a 15–2 pro who once fought live on ESPN. The younger and less experienced Quirk made news this past summer when he started giving boxing lessons to Patrick Dempsey, better known to Grey’s Anatomy fans as “McDreamy.”

I am a member of the Portland Boxing Club. This means I show up to the gym anywhere from one to four times a week to work out. I’m not much of a boxer, and I don’t pretend to be, but I love the sport and like to stay active. Once this past fall, Lamour interrupted his workout to help me perfect my jab, working with me on it for fifteen minutes or more. I had never had a conversation with Quirk, except to once excuse myself for accidentally cutting in on his heavy bag when he had taken a break. He insisted I keep working where I was as he took another bag about ten feet away. I watched him crack away on it, landing vicious body shots. His power and aggression stood in direct contrast to the genial way he had treated me.

Now I was going to the Expo to see these two men fight, fight and hopefully win. I can’t really say I was there to cheer them on, though. Whenever I find myself in a large gathering, I tend to shrink back into myself and become subdued. Even when I get excited I can never muster up the kind of enthusiasm I see everyone around me exhibiting. So I suppose you could say I was there to support Lamour and Quirk in my own quiet way.

I purchased my ticket at the box office and gave it to an usher. He told me to enjoy myself and I went through the turnstile. Just then, a McCloud lookalike—complete with mustache, shearling jacket, and cowboy hat—exited the restroom. I wondered what a fellow like him was doing in Maine. I got my answer when I entered the gymnasium in time to catch the ring walks for the next fight. The first to enter was a short, bulky light heavyweight wearing a big cowboy hat. He was from West Virginia. “McCloud” was obviously part of his entourage.

The whole place was dark except for the ring which was lit from above by a square lighting contraption suspended from the ceiling. It seemed to hover there, flying saucer-like, shining its light down on the canvas. I’ve been to a handful of boxing cards, but never one where the room was entirely dark.

People I knew were in the stands somewhere but I decided it would be too hard to find them, so I lingered near the entrance, leaning against one of the railings on the end of a row of bleachers. The interior of the Expo was massive and, with its intricate rafters that seemed oddly beautiful in the dark, reminded me of photographs I had seen of German train stations circa World War II. The crowd, packed tightly in the middle, thinned out toward the ends of the stands. Since nobody was currently fighting, many attendees were either still in line at the concessions booth or shuttling back to their seats carrying any number of beers. By the looks of it though, most had already had enough to drink.

I watched the West Virginia fighter, Austin Marcum, shuffle around the ring in his cowboy hat. When his opponent, Brandon Montella of Massachusetts, started his ring walk, Marcum went to his corner, took off his hat, and let his trainer help him out of his shirt. Montella got more applause than Marcum, but that was to be expected based on the tribal rule of proximity: root for your own and when you don’t have anyone to call your own, go for the one who lives closer. Even if most of the fans in attendance had never heard of Montella, they cheered for him because Massachusetts is closer to Maine than West Virginia.

In the first round, Marcum knocked Montella down twice. But in the second, Montella inflicted some damage and the crowd got to its feet and began to cheer and scream. It sounded like the noise of a conch shell amplified a thousand times. That noise, the noise of people calling for violence, startled me, and after a moment, I felt afraid—of what I’m not sure, but I think standing by myself with a mob of people around and above me yelling and screaming triggered some kind of survival instinct.

I have heard people say that boxing is too violent for them, a sentiment that never made sense to me until, on that Friday night, I experienced the same kind of revulsion. But it wasn’t the violence in the ring that made me feel this so much as the reaction of the spectators. When Marcum was knocked down in the third, the crowd roared, taking pleasure from the fact he could not get up and cheering as he started crawling about the ring like someone lost and deranged. It was a pitiful sight but no one seemed to care.

The referee ended the fight and a pop song—”Thunder” by Imagine Dragons—started up at deafening volume. I turned and gazed at all the dark shadows around me. Everyone, it seemed, was talking and laughing, the aisles suddenly full of people rushing out to get more beer. Two bald men in leather coats were laughing about something. A group of women in halter tops and tight jeans were dancing. Another young woman came dancing by me with her hands in the air as she sang along.

By the time Quirk made it to the ring, a friend from the boxing gym had spotted me and invited me to join her and a few others in the stands. With them I watched Quirk’s opponent, Mikael Bosse, make his ring walk to the strains of Sam Cooke’s classic hit “A Change is Gonna Come.” The song is about a man rejected by his family when he goes to them for help. Ultimately, it has to do with the hope that can come after, and out of, desperation. It’s been too hard living, but I’m afraid to die, crooned Cooke in the second verse. Cause I don’t know what’s up there, beyond the sky.

It was an unexpected change in mood. Accustomed to the kind of music that rallies people together by blotting out the ability to reflect, the crowd didn’t know how to respond. In the previous fights, some in the crowd had booed and jeered at the non-local fighters as they made their entrances but that contingent sat quietly now. We were all a bit confused because two disparate things were being asked of us. We were there as spectators of pugilism, there to cheer on legally sanctioned violence, there to abandon the usual requisites of civilized behavior. But now, through the music and lyrics of Sam Cooke, Mikael Bosse was asking us to have mercy for each other and I found myself thinking about what was really at stake in a prizefight, that other reality of boxing which most of us don’t like to think about. And so I sat there, feeling alone, and listening to the conversations around me.

“What’s with this fucking music?”

“Look what the guy’s wearing.”

“What the fuck is that? A skirt?”

“Looks like it.”

“Quirk’s gonna beat the shit out of him.”

“Guy looks like Tinker Bell.”

This last statement was accurate to a degree. Bosse had on a flap skirt, a garment boxers wear to be more theatrical and attract attention; Hector Camacho used to wear them a lot. But Bosse’s flap skirt was a rather delicate-looking garment with alternating petal-like sections of muted green and grey and with it he was wearing grey spandex leggings. And while the people around me jeered, I couldn’t help thinking how strange and lovely it was that Bosse had chosen to fight while wearing such an outfit and to walk out to such an unconventional entrance song. I watched with curiosity as this stocky, enigmatic fighter patrolled the four hundred square feet of roped-in space, waiting for his opponent.

Quirk made his entrance to music that was as forgettable as it was appropriate to the occasion. It elevated the mood in the room, and a certain clarity was reached as we all realized again why we were there: not to reflect, but to experience a spectacle, entertainment, a professional prizefight.

And what a fight it was, the best of the show. Hardly throwing a jab or punch to the face the entire match, Quirk worked Bosse’s midsection much the way I had seen him work the heavy bag in the gym and he ended the fight in the fourth with a right hook to the body. He also happened to drill Bosse with a final shot to the head after the referee had jumped in to give the count. Bosse was on his knees when Quirk hit him. Evidently the referee somehow missed this small detail. Bosse tried but could not beat the count and I couldn’t help flashing back to the lyrics of his prophetic entrance song:

Then I go to my brother

And I say brother help me please

But he winds up knockin’ me

Back down on my knees.

I’m sure most of the crowd saw the illegal punch but no one seemed to care. Their guy had won, and that’s all that mattered. Bosse, frustrated by the referee’s call, or lack of one, tried to protest, cupping the back of his head with one glove and pacing back and forth. He exited the ring before the winner was officially announced. As Bosse walked briskly off, the crowd jeered and taunted him.

Britney, my friend from the gym who had invited me to join her group, tapped me on the shoulder. “I’m going to get a beer,” she said.

“I’ll join you,” I said and followed her down to the gymnasium floor.

“I forgot to tell you,” she said. “I sparred for the first time today.” It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say she was beaming. “I was working out and Liz asked if I wanted to spar.” (‘Liz’ being three-time National Golden Gloves Champion Liz Leddy.)

“How’d you do?”

“Not great. It was awesome, though. I got punched in the face.”

Someone who has never sparred would probably have taken Britney’s excitement for either sarcasm or a sign that she was deranged, but I knew the rush that comes from getting smacked with a solid shot in the ring. The first time I sparred was at a small gym in southern California. I got hit in the face about a dozen times and heard the cartilage of my nose crackle. My mind was hazy for the next few days and my nose didn’t feel right for about two weeks. Only later did I realize I probably had a minor concussion and had broken my nose, which my wife recently observed now tilts slightly to the right.

What is it about fighting, about getting hit in the face, that can be so exhilarating? I had landed only one jab in my first sparring session and otherwise made wild swings that didn’t even come close to connecting, while my opponent spent two easy rounds barely working up a sweat. Yet I walked around for the next three weeks feeling invincible, stopping at random points during the day to shadowbox. Once I broke into a shadowboxing routine when walking in La Jolla and was brought back to reality by some teenage boys who laughed at me and asked if I knew the way to ‘Muscle Beach.’

“It’s really weird to get punched in the face,” Britney said.

“I know,” I said.

“One of the things I don’t understand about sparring is how hard you’re supposed to hit.”

That was a bit of a mystery to me too. “I don’t know,” I said.

“Me neither.” She shrugged. “Also, are you supposed to move out of the way in that kind of exercise? Because I kept getting hit in the head. My neck feels sore.”

“I think you should try to move out of the way as much as possible,” I said.

“Yeah, I think you’re right,” she said with a laugh.

Back in the bleachers, as we waited for the main event to start, I sipped my beer and tried to spot Ray Mercer, who had been advertised as the special guest of the evening. I expected him to make a speech and was looking forward to what the former Olympian and heavyweight champion had to say. I imagined him talking about the importance of these kinds of fights, the fights that don’t get much attention from the media or even the larger boxing community. But I was way off the mark.

After Russell Lamour and his opponent, John Thompson, made their ring walks, the announcer noted the presence of Rick Middleton, a former Boston Bruins player. After that, there was a confusing minute or so in which nothing happened. It seemed we were waiting for Middleton to either stand up or come to the ring, but Middleton either wasn’t in the room or didn’t want to be acknowledged.

The announcer introduced Ray Mercer next. Sitting ringside, Mercer raised both his hands, stood up, and spun 360 degrees. Then he entered the ring where he received a key from Portland’s mayor. Most of the crowd cheered for Mercer, but a small contingent of people started booing. I couldn’t figure out what that was about. Mercer then stepped out of the ring without saying a word—no speech from him or anyone else.

The contest between Lamour and Thompson was unexciting. Both were a bit twitchy, lurching forward just in time for the other to draw back. Thompson seemed more powerful, maybe because Lamour remained so inactive during the first few rounds. Once Lamour decided to fight though, it became a pretty even match. During the final round when it looked like Lamour might be doing some damage, the crowd started chanting, “Rus-sul! Rus-sul! Rus-sul!” But the chanting was a bit too eager, too early, and when fans realized they had misjudged the exchange and that Lamour wasn’t going to finish off Thompson, they slouched back into silence to witness the anti-climactic end.

As soon as the winner was announced, the ceiling lights switched on and people got up and walked toward the exit, trying to get through the doors before the bottleneck began. I stayed at the top of the bleachers for a moment and watched them make their brisk exodus. It didn’t seem many were particularly depressed by the result. People seemed tired more than anything else, ready to go home.

I was ready to do the same. I said goodbye to Britney before heading out of the Expo building alone. As I crossed Park Avenue, I wondered where Russell was and what he was thinking. I tried to remember if he had made his exit before most of the crowd. I couldn’t recall, but I hoped he had. Losing is tough, and I didn’t like the idea of Russell feeling he had let people down; or worse, feeling like people just didn’t care.

I started up the hill toward Congress Street, passing the apartment buildings and multi-family units along Weymouth Street. Portland is located on a peninsula that juts out into Casco Bay, and the Expo is located on the section of the peninsula that connects with the mainland. It’s on the edge of one of the few neighborhoods in town that remains working-class. There was a light on in a second-floor kitchen window of one of the tenements, and I looked up to see a woman hanging laundry.

For some reason I started to wonder if Ray Mercer had been paid to attend the fight. And if he had been paid, why, given that he had played such a minor role. Why had anyone thought to invite a special guest at all? I also couldn’t believe that mayors still handed out keys to their cities. It seemed to me ludicrously out of date, something that must have come into prominence in the postwar boom of the 1950s, when such a pointless gesture could be validated by an atmosphere of national optimism.

The man who had approached me earlier was still begging on the street corner. It was a blustery night. It occurred to me he was probably wearing safety glasses to blunt the wind. I crossed to the other side of the street just as two people came down the long concrete staircase from Maine Medical Center. One of them, a woman wearing a hospital gown under her short jacket, made eye contact with me. I looked away, glancing up at that tall, ominous medical building. Hospitals are scary places, even if they are where we go to get better. I thought about how I had spent a whole week in a hospital when I was in third grade. I was there recovering from a last-minute surgery that had saved my life. My intestines were twisted up, and a doctor opened my belly and put everything back in order. During my hospital stay, I got a card from my then best friend. “I don’t want you to die,” the note said.

As I opened the door to my car, I wondered what had made me remember that. I hadn’t thought about it in years. I knew it wasn’t only because I had seen a patient who had just been discharged from the hospital. But as I drove home, I realized why. It was because of Sam Cooke:

It’s been too hard living,

But I’m afraid to die

Cause I don’t know what’s up there

Beyond the sky.

— B. A. Cass

Forever and always we fight for none of us know who wins in the end…..mother of the boxer from little town northern Maine…. to my son acclaim that title fought, I scream, I cry, you win we fly! Brandon Michael Montella!!!