Serious Boxers Need Serious Managers

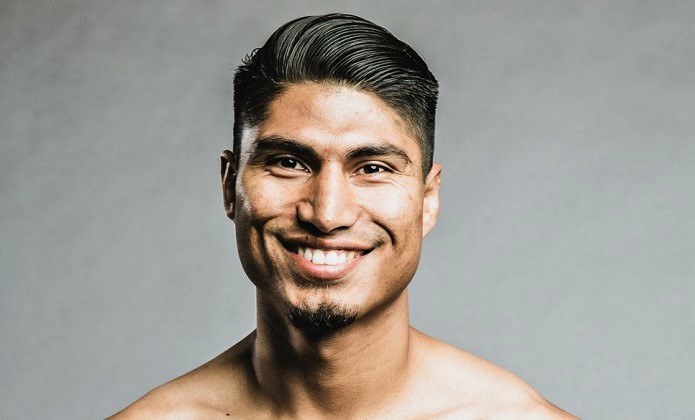

This column was originally published in February of 2020, following Errol Spence Jr.’s almost-fatal car crash, and after Gervonta Davis had been arrested for abusing a former girlfriend. But in the wake of Mikey Garcia’s upset defeat to Sandor Martin, and the fact that so many have since pointed to Garcia’s bone-headed decision (cited here) to move up in weight and fight Spence Jr. as the start of Mikey’s downfall, we feel the sentiment expressed in this column is as timely as ever. And bears repeating.

In the movies, they’re almost always unlikable, if not downright treacherous and crooked, their loyalties hopelessly divided between doing right by their fighter and doing what puts more green in their pocket. Sardonic and cranky, with an ever-present fedora or cigar, they agree to the risky fights, while taking no risks themselves, and let their prizefighter absorb the punches after making sure they absorb a big juicy slice of said prize. Think Maish in Requiem For A Heavyweight, or Tiny in The Set-Up. Managers. How do they sleep at night?

But maybe there’s another side to the story. Maybe managers, like it or not, are an important, if not essential, part of the equation when it comes to success in the fight game. Maybe, just maybe, a good manager is worth every penny that finds its way into his or her pocket.

Some while back I had an unexpected and intriguing conversation with an ex-boxer who at one time was under contract to the always mysterious Al Haymon. This fighter, now retired, declined going on the record, so I can’t name or properly quote him, but he expressed nothing but gratitude and admiration for Haymon, the norm it seems for boxers who join the man behind Premier Boxing Champions and the latter stages of Floyd Mayweather’s career.

According to this individual, the key reason that fighters like working with Haymon, beyond money, is that he offers unconditional support and an approach to career management that can be summed up in three little words: “You be you.” Reportedly, Haymon tells the boxers on his long and impressive client list that he is not interested in controlling them, in making decisions on their behalf, in orchestrating their professional life. Instead they are free to be who they want to be and to decide what direction their career should take.

In other words, Haymon is the antithesis of the crusty and compromised manager we see in the those old ‘film noir’ flicks, his management style more reminiscent of that fun teacher in high school all the students love, the one who never worries about due dates or bothersome things like punctuation and spelling, who encourages everyone to be as “creative” as possible. Put another way, Haymon, who has twice won the “Manager of the Year” award from the Boxing Writers Association of America, is a manager (assuming he actually is one; he is officially an “advisor”) who isn’t keenly interested in managing.

From the fighter’s point of view, this sounds great. Who could possibly be against the idea that boxers should be free to make their own career decisions? And what non-fighter could ever question this? While this website likes to remind everyone of the stupendous achievements of such past greats as Sam Langford and Harry Greb, one shouldn’t forget that those incredibly prolific careers inevitably took their toll. Fans and fight writers don’t take any punches, while no small number complain about how much it costs to watch fights from the comfort of their living rooms, with barely a thought for a pugilist’s well-being.

But the fight game has changed and boxers have never been more aware about the price they may end up paying for a busy career. We rightly hail Henry Armstrong for winning 27 fights in a single year, but for all we know “Homicide Hank” may not have been an enthusiastic participant every time he stepped into the ring in 1937. One imagines he may have even asked his manager for a little time off after notching his eighteenth or twentieth win that year. And for all we know that manager, one Eddie Mead, a well-fed sharpie who never lacked for the green required to place bets on both the ring and the track, took his cigar out of his mouth and said, “Can’t do it, Henry! You’re booked solid for the next four months. Just put some ice on that, you’ll be fine. Hey, next week we’re in Madison Square!”

So who can fault boxers for choosing to sign on with a manager who, for all intents and purposes, tells his fighters to carry on as they see fit, to march to the beat of their own drum? If they want to compete only once a year, fine, it’s their call. If they want to avoid the stiffest challenges, the opponents the fans want them to take on, hey, you be you.

But then again, recently there’s been more than one reason to think back on what that ex-boxer told me. And they haven’t been good reasons. Because the fact is a manager’s role, beyond helping with things like contracts, travel arrangements and training expenses, is to make good decisions that will maximize a boxer’s career potential. And to also help that boxer avoid making bad, outside-the-ring decisions that will do the opposite. But for a number of Al Haymon fighters, neither has been taking place. And that’s even when putting aside the tendency of so many in the Haymon stable to let their talent and physical prime wither on the vine.

To illustrate, let’s take a recent example, that being one Gervonta Davis choosing to publicly assault an ex-girlfriend at a basketball game. Now, needless to say, no one can fault a manager for this type of bonehead move. And ideally someone in Davis’ position would hold himself to a higher standard and treat people with a modicum of decency and respect. He is, after all, a potential star in boxing and a world champion. But beyond that, the fact Davis evidently felt at liberty to conduct himself in public as he did, speaks to a lack of guidance, does it not? Especially when one takes into account that Gervonta isn’t exactly unknown to law enforcement.

One imagines an astute manager might make it his business to keep tabs on their fighter’s personal life and, if needed, offer some unsolicited advice about how to deal with people. At the very least, sitting Davis down and expressing such sentiments as “Don’t be an asshole,” might go some way to helping a hot-headed young man make wiser decisions. And it wouldn’t require much in the way of time and effort to go further and maybe say things like, “Learn from Floyd. You want to end up in jail? Watch your temper. Take the high road, etc.”

But beyond all that blindingly obvious stuff, we happen to live in the era of the cell phone and the surveillance camera, and clearly someone should have sat “Tank” Davis down and explained to him that pro athletes are in fact under the microscope at all times; little they do is going unnoticed. Agreed, one would think this hardly needs pointing out, but these are pro athletes we’re dealing with, not candidates for Mensa. But that said, it only takes a few minutes for someone to remind a guy like Davis about how these days pretty much everyone carries a high-powered digital camera in their hip pocket. And the “someone” who should be doing said reminding, by all rights, should be the manager.

Naturally, one would prefer to rely on a client’s own judgment and maturity, or on the judgment of the people closest to said client, but ultimately, that’s just passing the buck. A serious manager understands that his client’s outside-the-ring conduct is his concern, that the idea that such things are “none of his business” just doesn’t fly. What a boxer does in his private life is, quite literally, the manager’s business. People who deal with pro athletes may resent having to take the role of a “babysitter,” but sometimes nothing short of that is going to safeguard a future star’s earning potential.

Take for example the situation of Errol Spence Jr. Now, to state the obvious, Spence is not the first, nor the last successful boxer, to respond to the allure of expensive, high-powered automobiles. But it’s one thing to buy such cars and use them to get from point A to point B; it’s something else to get loaded on Hennessy and then attempt aerial gymnastics with them. The surveillance video of the crash shows Spence is extremely lucky to be alive and at this point the jury is still out as to whether the injuries he suffered will have any affect on his career moving forward. But it so easily could have been much worse, and all the more lamentable when it could have been prevented.

Again, where was the manager urging Spence to not bother buying a Ferrari until after his career was over? Where was the manager admonishing him about his alcohol use after more than one video surfaced showing Spence in less than sober condition? An athlete’s career is necessarily short and the window for earning big money is small. It only makes sense for a person in Spence’s position to be focused first and foremost on being disciplined and living an athlete’s life so he can seize the opportunities while they’re available. And it also only makes sense for a manager who has invested time and money in Spence’s career to do everything in his power to make him understand that.

Let’s take a moment and speculate just where Spence would be right now if he had a wise and firm hand helping to guide him. Instead of having competed only five times in the last three years and not separating himself from the rest of the elite talents in the welterweight division, and instead of now facing criminal charges, he could and should be considered one of the pound-for-pound top talents in the game. He should be right now negotiating huge paydays for showdowns with Manny Pacquaio, Keith Thurman or Terence Crawford. What a waste!

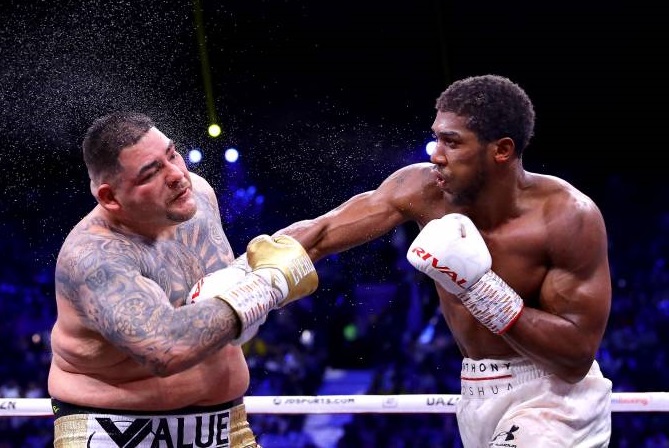

Similarly, just imagine where Andy Ruiz Jr. might be right now had someone tried to prevent him from sabotaging his own career and eating his way out of having any chance of winning his rematch with Anthony Joshua. The unheralded, roly-poly Latino heavyweight shocked the sports world last June with his seventh round stoppage of the undefeated “AJ” and a victory in the rematch would have meant not just more big money paydays, but status as a celebrity and a folk-hero to millions of Hispanics.

But for that to happen, training and discipline had to be a much higher priority than celebrating his unexpected win and ordering pizzas around the clock. Clearly Ruiz needed someone to save him from himself, someone to bust into his room in the early morning hours and chase his chubby butt out for his morning roadwork. Call me crazy, but I think we might call this ‘someone’ a manager.

Unfortunately, as human beings are known to do, Ruiz responded negatively to the pressure and expectations, stuffing himself full of antojitos and chimichangas instead of stuffing himself into the gym and staying there until he was in top shape. To everyone’s disappointment, he was in worse condition for the December rematch than when he had been called on short-notice for the first fight and he performed accordingly, showing none of the fire and quickness that had enabled him to overwhelm Joshua the first time around.

Immediately after the bout Ruiz cited his lack of proper conditioning, confessing to having partied too much and eaten too much, and he even publicly apologized to his trainer, Manny Robles. But it’s worth noting that no one in a managerial role was present to share some of the blame. If Ruiz owed Robles an apology for not being properly committed to his training regime, does Al Haymon maybe owe Ruiz an apology for not doing more to motivate his fighter and help him get focused on the task at hand?

And beyond these instances of boxers making poor decisions outside the ring, where is the manager to ensure PBC fighters are making good career decisions too? As mentioned, a boxer’s window of opportunity is necessarily small and it gets smaller with each passing day. And yet when Mikey Garcia decided he wanted to jump up and challenge Spence for a welterweight title, it seems no one tried to argue otherwise.

Again, this is why managers exist, to help boxers make smart career decisions. When the Spence vs Garcia match was first announced – a fight that absolutely no one was asking for – it was almost universally panned by hardcore boxing fans and pundits because it didn’t take a genius to see that a former featherweight taking on a talented welterweight in his prime made zero sense. While the brain-trust at PBC and Showtime billed it as a pay-per-view worthy showdown of undefeated champions, everyone else saw it as a match-up whose outcome was clear for all to see before the opening bell ever rang.

Say what you like about Garcia collecting a career-high payday, the simple fact is that after his less-than-excellent welterweight adventure – a fight in which Mikey failed to convincingly win a single round – Garcia is now worth far less on the open market than was formerly the case, and it will take both time and some significant wins for him to ever regain his former standing and his earning power. Again, it was just a bad move, a dumb career decision, and a smart manager would have talked Garcia out of it.

Now for all I know, Al Haymon is trying to do right by everyone in the PBC stable, and it should be mentioned that Haymon, legally-speaking, is not necessarily any boxer’s manager; perhaps he is merely an adviser and nothing more. But the point here is if he isn’t a manager, it begs the question as to who is. Because elite-level professional fighters need management. It would be good for both the athletes, and the sport of boxing at large, if more people recognized this fact.

Case in point: the next time a boxer gets behind the wheel of his Ferrari, he might not be as lucky as Errol Spence was. And the next time Gervonta Davis puts his hands on someone in public, he could be going behind bars. They might be bad guys in the movies with questionable motives, but the simple fact is there’s an important role for managers to play. And some fighters, whether they realize it or not, desperately need them.

— Neil Crane

Great piece. This is so true. You never see this with other promoters or managers. Paquiao never said anything about gay people and how they might have a first class ticket to damnation. Pernell Whitaker, Oscar DeLaHoya and Hector Camacho all had drug problems. No doubt those issues can all be traced back to Al Haymon. He either bought the coke or held the straw. We really need to put a stop to this guy trying to take over boxing. It’s really sad how Haymon has destroyed boxing. Remember Don King’s two week notice, take or leave it million dollar contracts??? What the hell has happened to boxing?

The fact of the matter is that these boxers are men, men who are responsible for and themselves and will be held accountable for the decisions they make. If it comes to advising on matchups, fine, a manager makes sense. But no one can be around 24/7 to monitor every move a fighter makes outside the ring. You need to stop looking to blame other people for a person’s mistakes.