Otis Grant: Winning On The Road

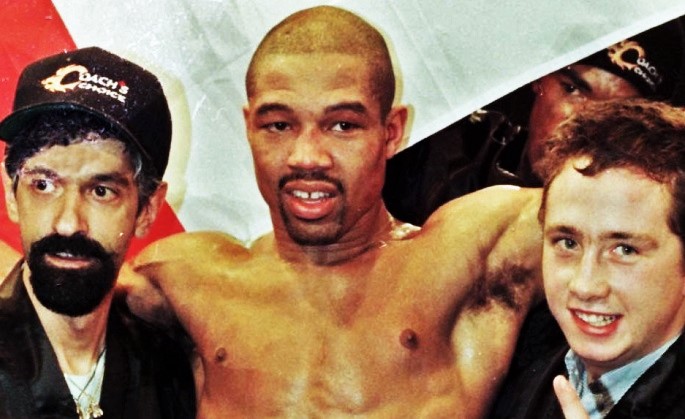

Today is a special day for fans of former world champ Otis “Magic” Grant as it marks the 25th anniversary of the high point of his career, his victory over Ryan Rhodes in Sheffield, England which won him the WBO world middleweight title. So no better time to re-feature our exclusive interview with Otis and his recollections on a milestone in both his life and his boxing career, the night when all the work and all those tough fights on the road were redeemed by the greatest prize pugilism can offer, a world championship belt. Check it out:

Twenty-five years since I won the title. Hard to believe. Yeah, it is the proudest memory of my career. I went into hostile territory, went into the other guy’s backyard, fought him, beat him, and brought home the belt.

It wasn’t my first try for a world title. Earlier that same year I had gotten a shot at WBO champ Lonnie Bradley and if you watch the video you can hear the commentators say before the last round that the champion needed something big to save his title. But the judges saw it different. They scored it a draw and when they announced it Bradley was pumping his arms and celebrating like he’d won big. Just shows he knew as well as anyone I got the better of it that night.

But that’s boxing. Bad decisions happen. I didn’t let it get me down and four months later I was back in the ring with a TKO win. Around the same time Bradley was diagnosed with a detached retina and had to vacate, so the WBO ordered a match between myself and Ryan Rhodes to decide the new champ.

It made sense for the fight to be in England where Rhodes could draw a big crowd. Of course I would have loved to have had it in Montreal, but bottom line, the money was in England so that’s where the fight happened, which meant I had to go to my opponent’s hometown to get my world title. And I was determined to make the most of this opportunity. I had come up empty-handed with my first shot and I knew chances for world titles weren’t exactly passed out like free candy. I had 29 wins in 31 bouts, had been fighting pro for almost nine years. This, for me, was a must-win fight.

So I went to my promoter, Art Pelullo of Banner Promotions, and took an advance on my purse. Looking back, I’m grateful for that. Not every fighter has that kind of relationship with their promoter, but Art and I got on good enough that I could go to him and say, “Hey, I need to take full advantage of this opportunity. I want to set up a proper training camp, eight weeks in England, travel, food, pay my sparring partners, cover all my expenses and do it right.” So he gave me an advance on my purse and that’s what we did.

We went over there and rented an upper apartment in London, in the Fulham-Chelsea area, and I had my team with me, my brother, Howard, and John Scully, who was my chief sparring partner, Russ Anber, my coach, and we’d train at a couple different local gyms, more than one gym so we could change up the sparring.

And what Rhodes and his people probably didn’t know was that I had family in England to help me out. Two aunts and uncles in Chelsea, so they looked after us and made sure we had everything we needed. We’d visit them on the weekends and they’d bring us food during the week. We didn’t have to rely on the promoter or my opponent’s people to get things or find places to eat. You do that and you run the risk of someone messing with your stuff. We had our own resources and no one even knew what we were doing. Rhodes and Frankie Warren and their people had no clue what I was up to.

Including where I did my training. Before this I actually did most of my training on the road, you could say, in New Jersey, because sometimes I needed to get away from the pressures of home and really focus. I’d work at the Second Street Youth Center in Plainfield, or sometimes I’d go to the Rocky Marciano Gym in Jersey City; that’s where Joe and Arturo Gatti liked to train. Guys like Glenwood Brown and Tracy Spann, who I knew from my amateur days, trained in Jersey too. And another boxer who trained there was Benny May, who happened to be from London, England, and Benny and I used to do roadwork together. So when I was getting ready to leave, I called Benny up in London and said, “Hey, I need a gym where I can train for the Rhodes fight, but I need it to be under the radar.”

Now in England they had a system which said amateurs and pros couldn’t train together. Over there you had pro gyms and amateur gyms and they were always kept separate. So Benny found me an amateur gym where I could go after it was closed. No one would be there and no one knew what I was doing. I would get to the gym around eight or nine at night and train until ten or eleven, and it made sense because I was getting ready to fight at night. So thanks to Benny I had access to this gym that no one knew about, and I could get my body used to working late, while doing everything under the radar.

In fact, we were so under the radar that I remember, about five or six weeks into camp, we got a message that Art was trying to reach us from Philadelphia. So I called him and he says, “Are you in England?” And I was like, “Of course, we’re in England. We’re here getting ready. That’s what I took the advance for.” But the reason Art was asking was because he’d got a call from Frank Warren’s office saying they sent a car to pick me up at the airport in London but no one came off the plane. We’d already made our own way over and been training for weeks and Rhodes and his people didn’t even know.

In total we were there for about two months before the fight and it was a great camp. Went running every day with Howard, sparring with Scully. When I went over there I was already in good shape, so the first week we just did running and got used to the time change and after that started focusing on the specific things I needed to do to prepare.

We were very comfortable, very loose. I remember one night, because we didn’t train on Sundays, John Scully said, “I’m going to take the train to Paris and tomorrow I’m going to eat a croissant under the Eiffel Tower.” So he leaves and the next night he’s back and showing everybody this photo with him standing under the Eiffel Tower, eating a croissant. It was that kind of camp. Relaxed, no tension, everyone positive.

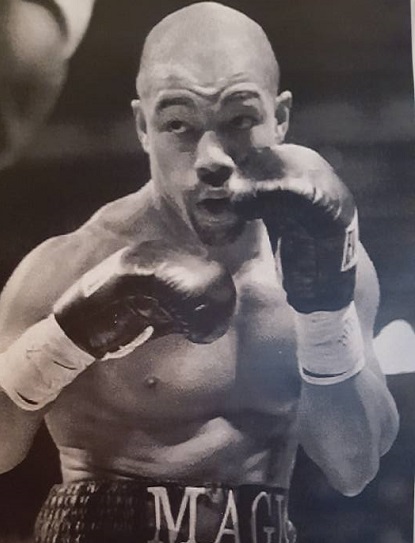

We watched a lot of video and took note of the things Rhodes didn’t do so well. We saw he tended to back up in a straight line so we looked to take advantage of that. Basically, the plan was to outwork him. He had a flamboyant style because he trained with Prince Naseem Hamed, ducking around and dropping his hands. The key was to be on top of him all the time, feinting, letting my hands go, keeping him on the defensive.

So we were training in London but the fight was in Sheffield, and when it came time to go up there, guess what? I had family in Sheffield too. So again, we didn’t need to rely on anyone. My father’s cousins were there and they came and took care of us. No matter where we went, we had our own people with us and that gave me confidence. But the fact is, I was already accustomed to fighting on the road anyway, so being in Rhodes’ backyard didn’t really bother me much to begin with. But having family in England, along with my team, it made that camp extra smooth and I’m grateful to everyone who helped.

Night of the fight, I remember the crowd was real boisterous and it was loud as hell in there. But then the bell rang and we got down to business and soon enough it got kind of quiet. I remember going back to the corner at one point, I think round four or five, and Russ said, “You took the crowd out of the fight. Stay focused and don’t give ’em a reason to get noisy again.”

The key was putting punches together. I never let him get control of the exchanges and just focused on out-working him. If he tagged me with one or two, then I jumped on him and threw four or five. Every time he backed up in a straight line I was on him and letting my hands go. He had that flamboyant, Prince Naseem style, and I just focused on taking advantage on whatever openings he gave me. His nickname was “The Spice Boy” because the big thing in England at the time was “The Spice Girls,” and I just never let him get ‘spicy’ on me, never gave him a chance to find his groove.

I was in shape to go twelve rounds, was never hurt, and I felt in control pretty much the whole way. To my mind, the fight really went according to plan. And I wasn’t worried about the judges because they were all neutral officials. Art made sure of that. Two American judges and an American referee. And because I had done most of my fighting in the states, those guys knew me so I wasn’t concerned about the officials. That was my promoter looking out for me. Though in the end I thought they scored the match closer than it really was. Again, if you watch the video, the TV guys had me ahead by five or six points, but the judges had me the winner by only one or two. Maybe the hometown crowd had affected the judges a bit, I don’t know.

Was it the toughest fight of my career? Not really. The tough fights had come before. I remember early on I fought a guy named Darryl Anthony and by the fourth round both of my eyes were swollen shut. And I remember fighting a guy named Danny Mitchell in Hamilton and he was built like a brick wall; when I hit him with my best shots he laughed at me. So I had already gotten through some hard fights and that prepares you for when you get your chance at a world title.

My toughest fight was Quincy Taylor in 1994. Man, that guy could hit. It was for the NABF title and after ten rounds I heard the television people at ringside saying it was dead even. So I pressed hard and won round eleven but I was so tired and in the last round I got clocked with a big left hand and down I went. I never heard, “One, two, three,” I only heard “five, six, seven.” I got up but I wobbled a bit and the referee stopped it. And later I found out I was ahead on all the scorecards and if I’d stayed away in the last round I would have won it. That was my toughest loss. Taylor went on to win the WBC title from Julian Jackson.

The point is, it’s those kind of battles on the road that made fighting a guy like Ryan Rhodes in his hometown something I could handle. Because you need to get tested along the way. There’s an old saying, ‘You grew up in the ring tonight.’ And you say that to a fighter when they’ve been hurt, or they’ve been knocked down, and they tough it out and get the win. When my eyes were closed against Anthony and I was taking shots and I had to keep going, that’s the kind of experience that makes you a better fighter. You learn how to handle adversity and overcome it.

And sometimes you have to take a chance and invest in yourself; you can’t always count on other people. I took my own money and paid my own way to be in England so I could get ready the way I wanted to get ready. I looked out for me instead of waiting for someone else to do it. I didn’t care that it was on the road. I was used to fighting on the road. Hell, I’d fight a guy in his own kitchen if I had to. Besides, I didn’t do it on my own. I could fight on the road and win because I always had a great team that was looking out for me.

So yeah, I won my title on the road. I went over to Sheffield, England, beat Ryan Rhodes in his backyard, brought home that belt. But where I really won it was in everything that came before. All that travelling, fighting in other people’s home towns, tough twelve round fights, learning my lessons the hard way. Yeah, I won my title on the road. More ways than one. — Michael Carbert