Otis Grant: Hometown Hero

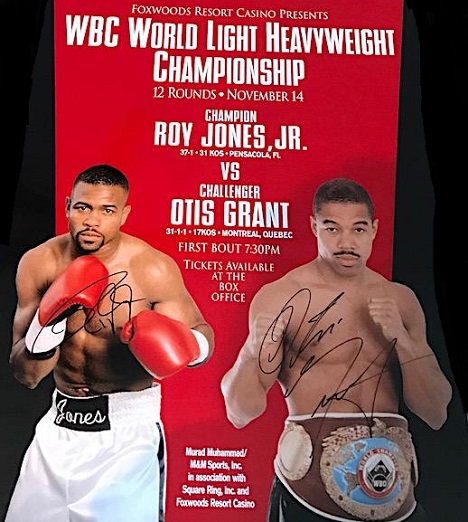

Otis “Magic” Grant is more than a former world champion boxer, much more than one of Canada’s most successful athletes. As an amateur, he won provincial and national championships and a silver medal at the 1987 Pam Am Games. As a professional, the cagey southpaw was a major force in the middleweight division for much of the 1990’s, winning the WBO world title before moving up in weight to challenge a prime Roy Jones Jr. But his ring accomplishments, while impressive, don’t come close to telling the whole story about the man. To understand who Otis Grant is and to appreciate what he means to the city of Montreal, you have to dig a little deeper. Because Otis Grant is that rare thing, a genuine hometown hero, in every sense of the term.

Sitting down with Otis to get some time for an interview means interfering with serious business. In his office at the gym he co-owns with his brother Howard, hunched over his computer, scrutinizing forms, answering the phone, Otis is the picture of a man besieged. Such is your lot when you not only operate one of Montreal’s most active boxing gyms, but also help manage different boxers, both amateur and pro, and support different community and charitable ventures. Contracts, bookings, licenses, medical exams, demands from promoters and athletic commissions: the list of headaches is long.

But despite the hectic nature of the work, Otis is clear on one important fact: he is doing exactly what he wants to do.

“Absolutely. It’s a tough business, but this is what we know. My brother’s good in the gym with the fighters and we work well together. We’re a good team.”

Howard and Otis, less than two years apart, were always close, having together made the journey from Jamaica to join their parents and start a new life in a new country. As kids, the usual summer time routine in their new community of Ville Saint Laurent involved plenty of basketball and swimming in the public pool, but then one of the gang discovered the local boxing gym. Howard and Otis started to learn how to box and before long the Saint Laurent Boxing Club served as a home away from home, the place where the brothers wanted to be when they had extra time.

“We started in the summer but then we kept going and it was close to school,” remembers Otis. “So we’d go there after school and our parents liked it because they always knew where we were. Then we started competing at amateur shows, and then at the provincial level, then the Golden Gloves, then Nationals, then represent Canada, the international circuit, and then, after Howard went to the Olympic Games, we turned pro.”

Just like that. One day you start working out in a boxing gym for fun, the next you’re winning medals at international competitions and getting ready to turn pro. Happens all the time, right?

This brusque, matter-of-fact delivery is typical of Otis, a man with zero interest in hyperbole or self-aggrandizement. Instead, the younger of the Grant brothers is quick to deflect praise and point it elsewhere. Howard, he remarks, was in fact the more talented boxer, an “excellent amateur, one of the best amateurs this country ever had,” while his own pro career, which entails more than one world title belt, he terms merely “respectable.”

But this is consistent with the former champion’s character and outlook, one focused less on highlighting his own achievements and more about giving back. That desire to help others is rooted in a strong sense of community. Throughout his pro career, Otis had numerous chances to leave Montreal, to establish himself in Philadelphia or Las Vegas, but he never left his home city. “There were people who thought I should move to the U.S., but I never wanted to. I grew up here, my family was here, and I like it here. I’ve traveled all over the world, but for me, I love Montreal.”

Loyalty to his home city had a direct role in the most traumatic turning point in Grant’s life. Having won a version of the middleweight world title and gone ten tough rounds with Roy Jones Jr., Otis was hoping to be released from the final months of his contract with Banner Promotions so he could have a chance to re-establish himself in Montreal. Returning from a meeting held to discuss that possibility in June of 1999, Otis was behind the wheel while his friend and former boxer Hercules Kyvelos sat in the passenger seat and Otis’ six-year-old daughter was in the backseat behind Hercules. Coming over a hill on a stretch of highway, Otis saw a car heading in the wrong direction and coming straight for them at high speed. With no time to avoid a collision, he swerved the vehicle so the impact was taken on the driver’s side, sparing the passengers.

Several other cars were involved in the tragic mishap which saw numerous injuries and one fatality. Taken to hospital in a separate ambulance, a distraught Otis would not relax and allow himself to be tended to until he knew his daughter’s condition, and when finally told she had suffered only minor scrapes from broken glass, he immediately lapsed into a coma and didn’t wake for seven days. The impact of the crash had broken Otis’ shoulder and several ribs, punctured his lung and shattered his shoulder blade. Doctors later told him that had it not been for his superb physical condition, the violence of the collision would have killed him. They also told him he would never box again.

How easy it would have been to descend into bitterness and regret. One minute you’re focused on the future, still young and healthy, looking to revitalize your career, and the next you’re being hauled into an ambulance, all your plans and dreams as devastated as a shattered shoulder blade. But Otis Grant didn’t see much point in getting down about things. The way he saw it, he was happy to be alive, happy to still have his family, happy to have any future to look forward to. What many didn’t know at the time was that Otis’ wife was pregnant with their second child. A boxing comeback never entered his mind until long after he knew his daughter was fully recovered from the trauma of the crash, until his young son was out of diapers and looking forward to his first day of school.

Montreal had rallied around Otis after the accident and, touched by the concern for himself and his family, the former champion wanted to give back. When asked to lend his name to a local charity effort working to distribute food to needy families, Otis signed on. And when he saw the extent of the need, as well as the difficulties of distributing all the food, he decided to start his own charitable organization. Thus, the Otis Grant & Friends Foundation was established, which works to support various charities and non-profit organizations on the island of Montreal.

Meanwhile, months of physiotherapy were required just to restore natural movement to Otis’ left arm; to this day, he cannot raise it a full ninety degrees. He was now working as a teaching assistant and counselor for special needs students at a local school, but Howard was training fighters at George Cherry’s Champions Boxing Gym and was getting Joachim Alcine ready for his next opponent, a southpaw. Solid sparring partners were proving difficult to find and one day Howard asked Otis, “You think you could work with him a bit? Get in the ring? Move around a little?”

At this point it had been years since Otis had last sparred, but the request sparked something. “Give me a couple weeks to do some roadwork, get my wind back,” said Otis. The former champion sparred with the future champion and Alcine won his fight. And just like that people were talking about how good Otis Grant looked in the ring, how the accident hadn’t taken too much out of him, how the “magic” was still there.

“The main reason for the comeback was so Howard and I could open up our own gym. But it wasn’t a stunt or just for money. I fought good fighters, ranked contenders, ex-champions. And I got myself back to the top of the division.”

After months of hard training and getting the green light from a sports medicine doctor, Otis “Magic” Grant returned to the ring in 2003, four years after the car accident, four years after the doctors said he would never box again. With Howard as his trainer, he went on to win six consecutive fights, all of them fought in Quebec, four of them in Montreal. In 2006 he faced tough Librado Andrade, the winner to receive a title shot against WBC champion Mikkel Kessler. Suffering two knockdowns, Otis conceded defeat following the seventh round, saying afterwards it was his time “to bow out, and bow out gracefully.”

“I didn’t come back to lose,” says Otis. “I wanted to give it a good shot, see how far I could go, and get enough money for the gym. No need to go on and risk my health.”

Instead it was time to start up a serious boxing gym in fight-mad Montreal, time to start nurturing and promoting local talent, time to keep giving back to the city he calls home, and to work side-by-side with Howard while doing it.

“I know the best guy in the world for me to work with is my brother. Because this business can be so shady and so crooked, you got to look out for each other. And we’re not going anywhere. When I was a pro, if I had a dime for every guy who came along and offered me the world if I’d pick up and leave Montreal, I’d be a millionaire. But I was never tempted. Montreal is my home.”

Finally, when the self-effacing Otis Grant is asked to look back on his career and point to his proudest moments, he highlights three things: winning the world title in his opponent’s backyard when he defeated Britisher Ryan Rhodes in his hometown of Sheffield, England; returning to boxing after the car accident and re-establishing himself as a legit title contender; and finally, starting up the Otis Grant Foundation and helping untold numbers of people in his community.

Talk about a hometown hero.

— Michael Carbert