The Making Of Mike Tyson

It’s odd seeing something you have lived through presented as history. Aside from the sense of mortality that it engenders in a person, there is also the natural thought that, “I was there. What do you have to tell me about it?”

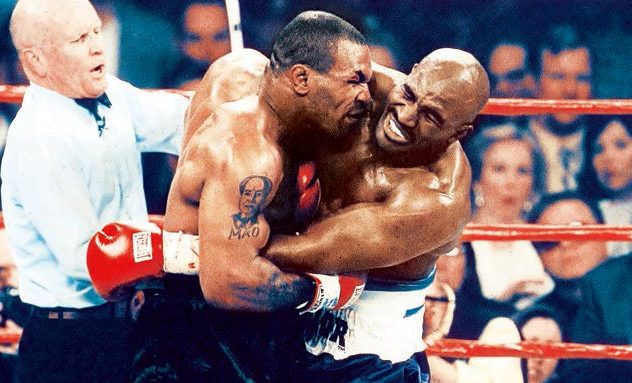

I was born in 1980, so Mike Tyson has a permanent place in my sports and cultural memory. Tyson is Nintendo’s Punch-Out. Tyson is Drederick Tatum on The Simpsons. Tyson is biting Holyfield’s ear, which I witnessed live while sitting in my friend’s backyard with a TV set up outside just for that Showtime card. Tyson is those things and more, for almost everyone. How can a biography tackle something so ingrained in the memories and experiences of so many people?

Mark Kriegel’s Baddest Man: The Making of Mike Tyson manages this tricky feat with a few deft choices. First, Kriegel sticks to his conceit. This book is about how Tyson came to be. It begins with his birth, but ends with the demolition of Michael Spinks in 1988, arguably Tyson’s apex as a fighter and a cultural icon. This allows the author to deeply explore people and events that a more comprehensive biography might not be able to.

Next, Kriegel writes in a clear but not overly-simplified prose. This is journalism, but with a linguistic flourish appropriate for a subject who reached the heights of fame known to very few people, let alone athletes, and which are now unthinkable for even the best boxers today.

Finally, and most impressively, Kriegel explains his subject without excusing the bad behavior. This is how a book about something many of us lived through can be fascinating. Kriegel never tells the readers they’re wrong for thinking a particular way about Tyson, but he provides plenty of context for readers to better understand Mike. He evokes empathy without any hint of endorsement or forgiveness for the awful things Tyson did.

Kriegel includes some elements of the Tyson story, which he must, that most boxing fans will already know. Mike loves pigeons. Mike grew up in one of the worst urban neighborhoods in America. Mike was an extraordinary student of boxing. But Kriegel, as the best biographers do, provides details that make those abstract ideas more concrete and vivid. For example, Kriegel on Tyson’s early studies of Nat Fleischer’s The Ring Record Book and Boxing Encyclopedia:

“Tyson pored through that hefty volume as if deep in Talmudic study, reading, as best he could, memorizing the images, absorbing their stories, descendants of Hebrews and Hibernians, Germans and Negroes, men who’d survived their own Brownsvilles, their own abandoned buildings, only to prosper and conquer and be adored…”

Passages like this one, and there are plenty, help to tie Tyson’s early experiences together. His deep dive into boxing history isn’t just to become a better fighter, but also because he felt genuinely connected to those old champions. We see that Brownsville was the conduit to Tyson becoming a boxer. And, unlike the many others who saw boxing as a way to get out of poverty, Tyson was motivated by an intellectual and emotional connection to the fighters of the past, as much as his desire to get rich, if not more so.

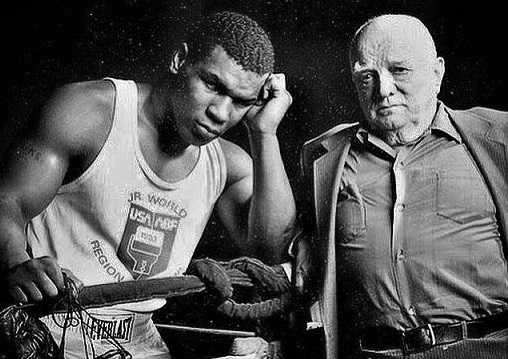

That emotional connection to past pugilists informs Tyson’s journey and his relationships with his fellow combatants. Kriegel shows us that, despite the image of relentless cruelty that manager and father-figure Cus D’Amato helped Tyson to craft, a deep and real connection to his peers remained. “Whatever pathologies Tyson had acquired, for all his jailhouse bluster, his great, enduring empathy is for fellow fighters. If they weren’t quite a family, then perhaps a fraternal society.”

Nowhere is this connection to the past more interesting, and bizarre, than in Tyson’s understanding of Artie Diamond. Diamond was in D’Amato’s stable decades before Iron Mike, but he became legend among D’Amato’s pupils. After his boxing career, Diamond went to prison, and on his first day was confronted in the yard by a giant of a man. What followed sounds familiar:

“Diamond nods knowingly, leans in close as if to whisper something. Then he bites, clamping down on the Black guy’s ear… Then, for the everlasting memory of those in the gallery, that they may swear ad nauseam to what they’ve seen, Artie Diamond spits out the bloody ear in pieces.”

These are the kinds of legends Tyson grew up on with D’Amato. These were the stories told with reverence. Kriegel does not write much about the fights with Holyfield, but he does provide these kinds of connections, and because he knows how ingrained in culture “The Bite Fight” is, he doesn’t need to do more than put the info out there and let the readers make the analysis themselves.

Finally, Kriegel addresses the issue of race in the legend of Tyson, and does so throughout. From Brownsville and street cred, through the crack epidemic that exploded at the same time as Tyson’s fame, to the burgeoning hip hop scene. As Kriegel says, “Nobody transcends race, not in America.”

What I found most interesting was how race and control interplayed. Tyson was under the tutelage of D’Amato, Teddy Atlas, and other white men as he developed. And while there are many significant black characters in Tyson’s story, not the least of whom is Don King, white men controlled the narrative.

But then Tyson broke out, almost unwillingly. He became too big to control. Kriegel narrates this in detail, but one of the most interesting moments is Tyson appearing in a Public Enemy song: “‘Cause I can go solo, like a Tyson bolo/Make the fly girls wanna have my photo.” As Kriegel writes:

“Never mind that neither Chuck D nor anyone else had ever seen Tyson throw a bolo punch. Tyson had now entered the zeitgeist in a way that hadn’t been scripted by a white man.”

And this brings me back to being there. Because I was there, but I was a kid who loved watching a sporting legend. And then I was a teenager who was fascinated by the train wreck Tyson became. And then I was an adult who saw the man recover and reestablish himself as a beloved icon.

Of course, there are different levels of “there.” If this type of book is a good one, the reader does not relive an event as much as they feel like they were more “there.” This is what Kriegel’s work does. For anyone who saw it all live, there’s yet another layer waiting for you, and it’s a fascinating one. — Joshua Isard