McIlvanney On Boxing

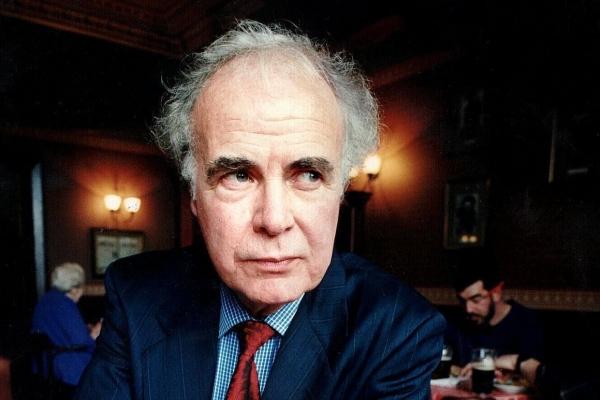

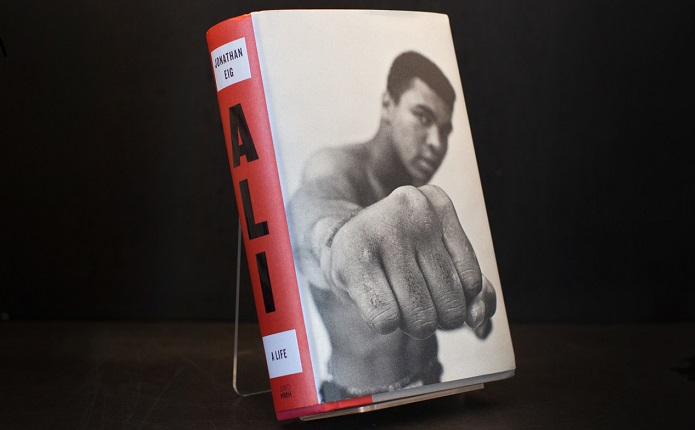

A.J. Liebling will always be boxing’s literary standard bearer, his masterwork The Sweet Science and other books certain to find appreciative fans through the generations. If there’s a top table of boxing scribes, no doubt Liebling is at its head. However, my fellow Scotsman, Hugh McIlvanney, undoubtedly warrants at least a seat at the same table, a sentiment expressed by many when the esteemed journalist died in 2019 at the age of 82.

As a sportswriter, Hugh showcased his tough lyricism, marvelous originality and piercing observation during several decades covering the fight game for The Observer, The Sunday Times, Sports Illustrated and other esteemed publications. A selection of his finest reportage is assembled in his seminal work, McIlvanney on Boxing, which originally appeared in 1982 but has since been re-released. My own copy came out in 1997, meaning a substantial portion of the book deals with eminently writeable figures such as Mike Tyson, Evander Holyfield, Riddick Bowe, Lennox Lewis and Julio Cesar Chavez. In the hands of a master craftsman like McIlvanney, the exploits of these fistic luminaries are writ large, their personalities blown up to god-like proportions.

Until I picked up the ’97 edition of McIlvanney on Boxing, I had been less familiar with Hugh’s output than his brother’s. For the unfamiliar, his younger sibling, William, is regarded as one of Scotland’s greatest novelists, his 1975 work, Docherty, considered a classic. Having devoured a number of William’s books, I could be forgiven for thinking Hugh might fall short of those impossible standards, but just a few pages in and such reckless assumptions were thoroughly dynamited.

There are many similarities between the two, not least a gift for simile and metaphor; an ability to imbue the simplest, most straightforward gestures and conversations with a mighty sense of gravitas, and a very real empathy for one’s fellow human beings. The writing in this compendium – like William’s (and Hemingway’s, incidentally) – is tough yet stylish; unvarnished, yet effusive in its navigation of deep and subtle emotions. In other words, the kind of writing perfectly suited to the unforgiving but paradoxically rewarding world of pugilism.

The book opens with “The Case Against Boxing,” a short but punchy piece about the intermittent clamour for the abolition of the sport McIlvanney dearly loves. The writer makes no bones about his moral ambivalence, though he does take abolitionists to task for oversimplifying their arguments. “Aggression is central to all competitive sports,” he reasons, “and it would be astonishing if there were not many young men left dissatisfied with the sublimation of it involved in ball games, in track and field athletics, in adventure pursuits such as mountaineering or in the racing of horses or machines. Such natures hunger for the rawest form of competition and that means boxing.”

The pieces that follow are divided into five parts: “The Alpha…”, which covers Ali’s career from 1966 to 1975; “Some of Our Own Who Could Have a Row,” which features stirring accounts of battles involving Terry Downes, Walter McGowan, Ken Buchanan and others; “Prodigies and Prisoners,” “…and the Omega,” a section chronicling Ali’s inexorable late ‘70s decline, and “Further Dispatches,” a brilliant array of pieces spanning 1985 to 1997.

Shot through with arch humour and an admirable attention to detail, these are surely some of the finest boxing articles ever printed. It’s telling that McIlvanney remains the only sports writer to be named Journalist of the Year, in addition to seven wins for Sports Journalist of the Year. These professional victories were as much a mark of his obsessive detail and accuracy as his engaging and eloquent style.

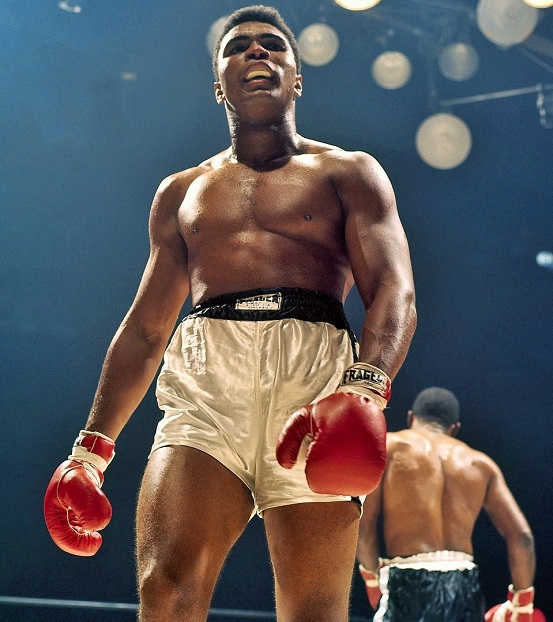

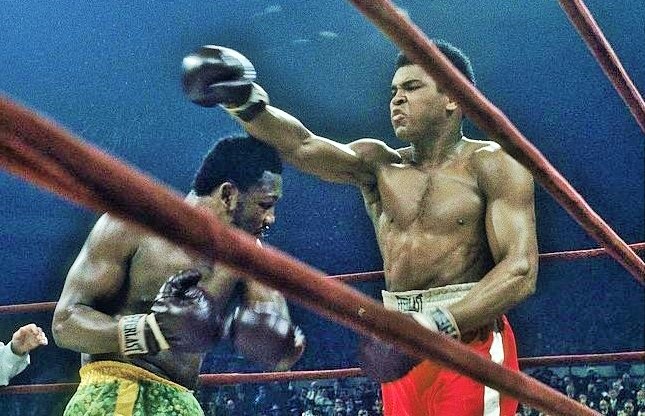

Naturally Ali is a figure to whom McIlvanney – like so many of his fellow scribes – was strongly attracted. The early pieces are befitting of The Greatest, in that they set his towering achievements in proper context and recount them with frequent reference to the deep reserves of courage, will and talent they necessitated. “At his best,” writes McIlvanney, “his unequalled mobility made him as secure as a dive-bomber attacking a wagon train.”

It’s not all about Ali’s prowess in the ring though, for McIlvanney extracts meaning and substance from more than his gloved exploits. He understood what Ali represented, his significance in the canon of boxing lore and his wider appeal as an outspoken black American. Although there have been millions of words written about boxing’s most celebrated star, McIlvanney was one of comparatively few to whom Ali held court. “On a street called Topaz in New Orleans, in a villa by the Zaire River outside Kinshasa and on the seafront in Nassau, Bahamas, in the hour before dawn, I was fortunate enough to record some of his more private reveries.”

As a consequence, there’s an undeniable credibility behind observations such as this one: “Ali seems to see his life as a strange, ritualistic play. It may be that the explanation of his rantings is that he has always felt they were required by the script that goes with his destiny.” Others still sparkle on the page, reflections of Ali’s own blinding luminescence: “Compared with him, the most vivid of his predecessors are blurred figures dancing behind frosted glass.”

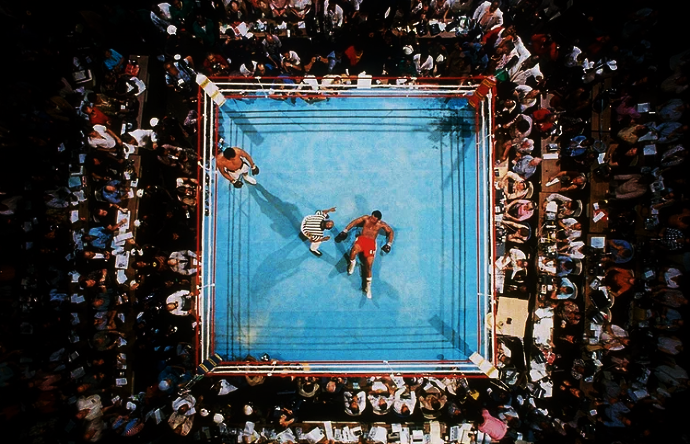

When the “Louisville Lip” suffered defeat to Smokin’ Joe Frazier in 1971, his first professional loss, he was enlarged in the eyes of McIlvanney and in the brilliantly titled piece “Superman at Bay,” the author writes: “Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of that utterly remarkable heavyweight championship fight in Madison Square Garden is that defeat, far from diminishing Ali in the eyes of his admirers, has deepened their feelings far beyond the normal limits of public respect and affection.”

Of course Ali would rise, phoenix-like, to exact revenge on his arch nemesis three years later, before shocking the world in the era-defining “Rumble in the Jungle.” On that immortal night, McIlvanney rates Ali’s moxie above his arsenal of physical weapons: “When all the outlandish trappings of an extraordinary event have begun to fade and gather dust in the memory, when we have grown vague about the wheeling and dealing involved, about how ethnic pride and financial avarice became ardent bedmates… what will remain utterly undiminished is the excitement of Muhammad Ali’s performance. And for this witness at least the most vivid recollection will not be the inspiration of his tactics or the brilliance of his technique, spellbinding though they were. It will be the glittering, flawless diamond of his nerve.”

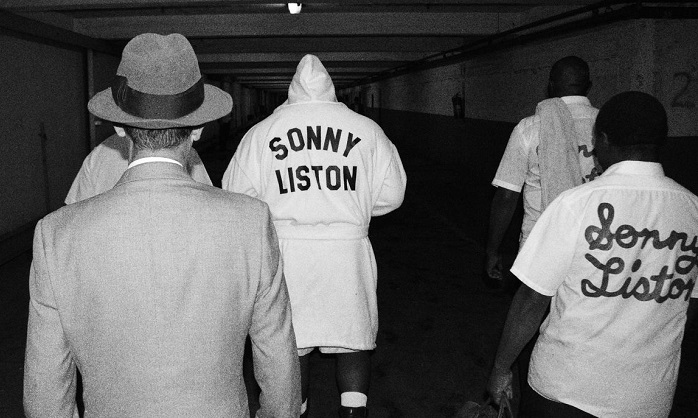

You could say that Ali is an easy character to write well about, given his larger-than-life personality. And it is true that many fine books have taken Ali as their subject. However, McIlvanney proves equally adept at translating the sheer physicality and murderousness of some of boxing’s less garrulous prizefighters. Chew on this sublime nugget, which describes the Foreman vs Norton confrontation: “The impression was that Norton’s spirit had been anaesthetised by the implacable presence of Foreman, that he was a victim awaiting his doom. There was never any possibility that he would have long to wait. The 25-year-old world champion has now grown to a full awareness of his fearsome capacity for destruction.”

George Foreman’s technique, let’s be honest, was fairly agricultural, even as he cut a merciless swathe through the heavyweight division. But where lesser writers would focus solely on his atomic power, the passages here sketch a wonderfully vivid and terrifying picture of relentlessness. “The pulverising blows tend to come from both hands in long arcs, sweeping diagonically to his opponent’s head, and the vast arms often brush contemptuously through efforts at parrying defence… He quarters the ring with a deadly sense of geometry, employing a perfectly timed side-step that cuts off escape routes as emphatically as a road block.”

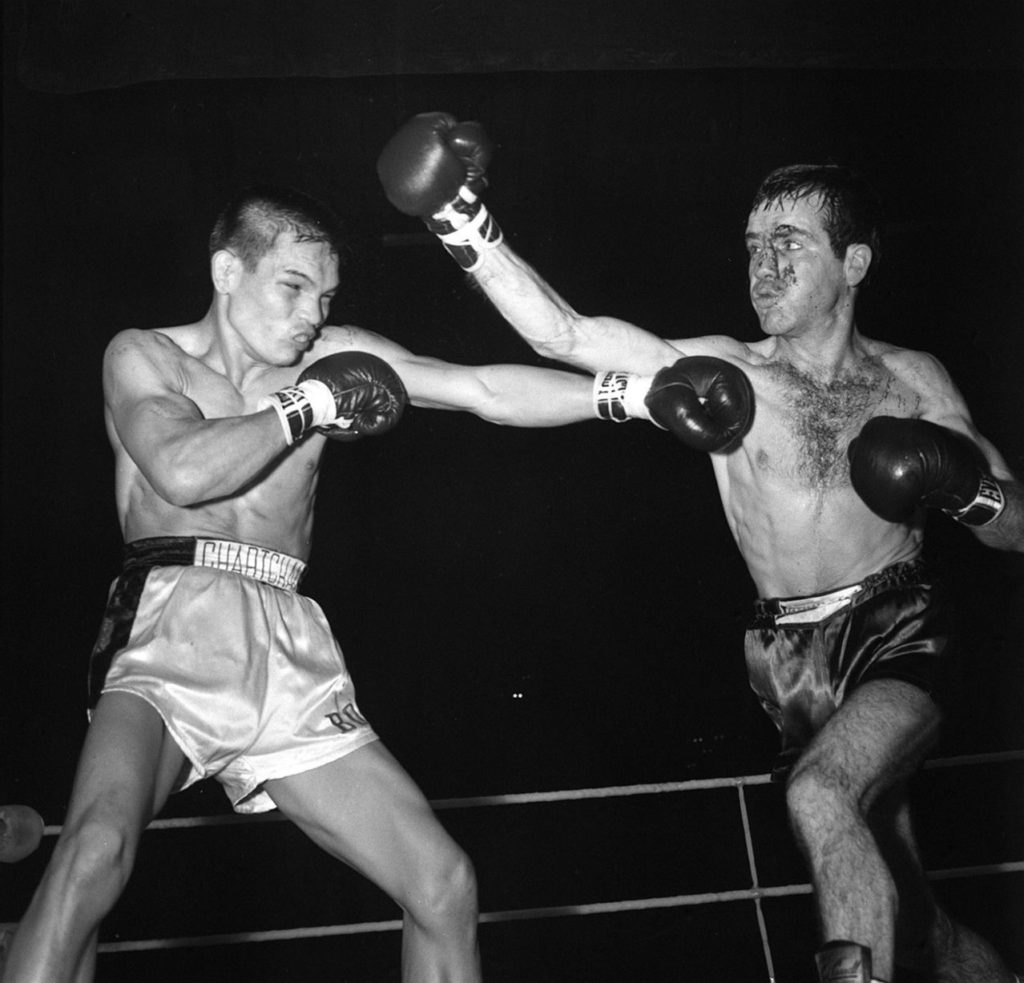

“Part Two: Some of our Own Who Could Have a Row” contains a number of terrific pieces, of most interest perhaps to British fight fans. I enjoyed reading more about Terry Downes, Howard Winstone and Walter McGowan, three fighters whose careers I’d never investigated.

At the risk of going off on a tangent, my old amateur coach John McDermott – who won the Commonwealth gold medal at the 1962 Games in Perth – was quite fond of McGowan. Walter hailed from Hamilton, just a few miles from the boxing club McDermott founded in Blantyre, and the pair were about the same age. McIlvanney writes of McGowan that “he had just about the best hands I have ever seen on a boxer from these islands, and his extraordinarily fast, varied, damagingly selective punching made him the most precociously brilliant amatuer.” And by all accounts, John McDermott wasn’t bad either!

In any case, McIlvanney casts his discerning eye on McGowan’s second duel with Chartchai Chionoi, Downes’ showdown with Willie Pastrano, and Winstone’s hard-fought defeat to Vicente Saldivar. Reading about these wonderful skirmishes from the 1960’s is a pleasure, with the fascinating characters and subplots matched by the sheer dynamism of the writing itself.

As well as capturing his subjects’ individual traits, McIlvanney describes the qualities that define truly magnificent fighters with enviable incisiveness. As evidence, here he explains the destructive modus operandi of Mexico’s Gran Campeón Julio Cesar Chavez:

“For opponents, Chavez brings a quality of nightmare to the ring, pressing in so remorselessly that he seems to surround them, allowing no escape from the percussive intensity of assaults mounted with a patient, apparently passionless fury… Once he has begun to rip the substance out of his man with rhythmic pounding of the torso, the mastery of range that governs his punching enables him to switch smoothly to the vulnerable head, and every time one punch lands several others are almost sure to thud home with equal accuracy.”

His subjects needn’t be flawless to receive such trenchant analysis. Consider this description of Lennox Lewis, then ascending the heavyweight ladder in the mid ‘90s: “His self-belief, fed as it is by all the evidence that he does indeed possess the priceless gift of rising above the difficulties he creates for himself with erratic, often slovenly technique, and somehow finding a way to win, is surely his greatest asset …”

Suffice to say, I could happily quote from this collection all day long. But the best advice I can give you is to buy McIlvanney on Boxing and discover for yourself what an enriching read it is. Of course, there’s always time for one last excerpt, and this one deserves to be savoured.

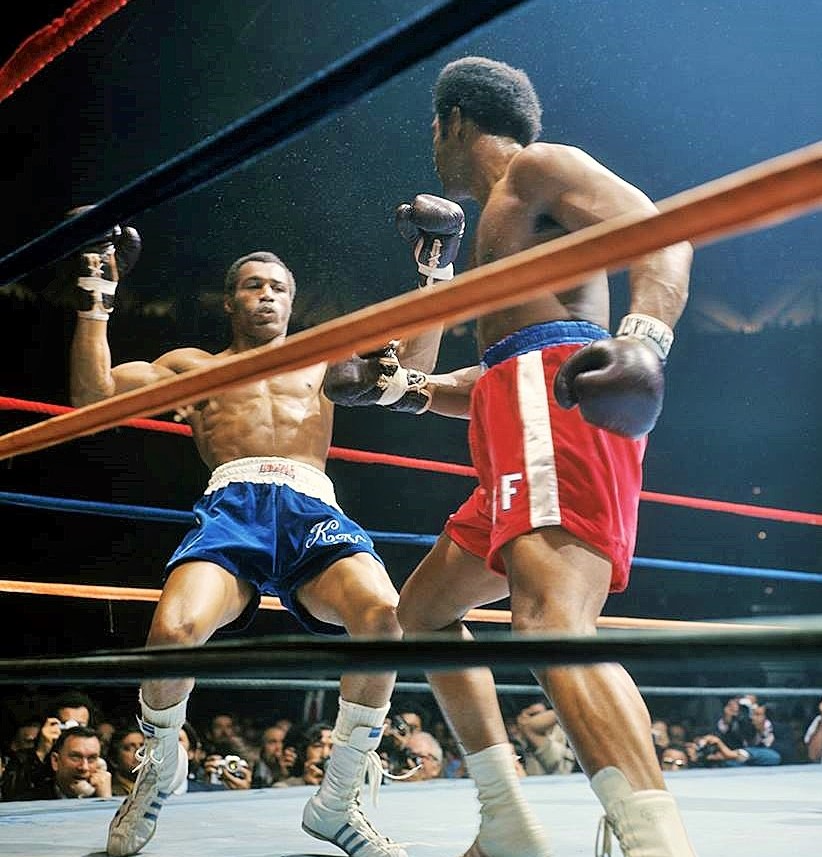

“Only deep reserves of intuition or prejudice could permit someone to be dogmatic about what will happen when Leonard, whose speed, spontaneous ingenuity and technical range make the word virtuosity unavoidable, collides with the outlandish physical attributes of Hearns, who has a reach that is a threat to chins in the next county and develops enough leverage when he punches to knock down a small building.”

As we know, the fight in question was a classic and is still talked about to this day. You can say the same about McIlvanney on Boxing. — Ronnie McCluskey

You can never have enough excerpts, so I’ve noted a few more below – Ronnie.

(on Whitaker-Chavez): “This was an enthralling conflict between champions of the highest calibre and fiercest commitment, men too serious and knowledgable about their violent trade to regard Corinthian etiquette as a priority on such a night.”

“The five rounds it took to reduce Haugen to a penitent wreck afforded Chavez scope to display barely half of the frightening arsenal of destructive gifts he has perfected.”

(on Holyfield-Moorer)” “The lack of speed and fluency and sustained cohesion that became increasingly marked in Holyfield’s work as round followed round seemed to have more to do with the sediment of profound weariness left in the marrow of his bones by exposure to too many wars.”

Great read, thanks!

Magical stuff.