Overfed Turkey Or Sleek Bird Of Prey?

What a difference two years can make.

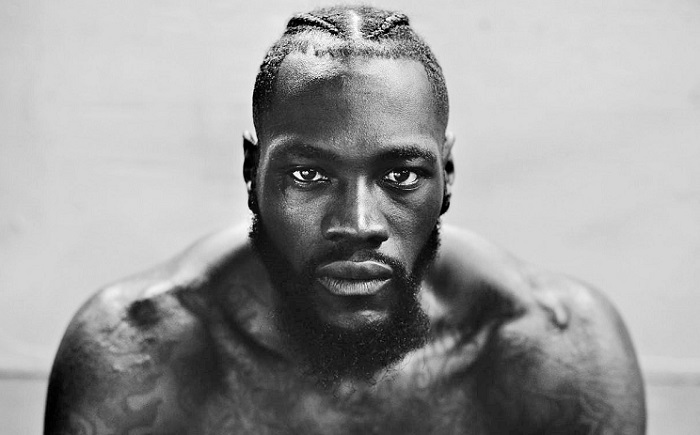

Back in 2017, the WBC belt-holder Deontay Wilder had just fought Gerald Washington, the latest in his long line of scrubs, to deservedly zero fanfare. Widely mocked for his gangly, uncoordinated fighting style, and unable to draw a crowd even in his Alabama backyard, Wilder must have been on the verge of being offloaded by his promoters, Al Haymon and PBC.

Undefeated and with 38 knockouts to his credit, and technically able to call himself a world champion, Wilder’s career had all the stretch marks of a turkey being fattened for the Christmas of a big money blow-out against a real fighter. His defenders – not many, admittedly – said at the time that that kind of record speaks for itself. They’d understandably never heard of LaMar Clark, who was 42-0 with 42 knock-outs until he was upset by the even more obscure Bartolo Soni before he could be fed to the churning maw of Sonny Liston. Or Donald “The Man of” Steele, 41-0 with 41 knock-outs by the time he was whipped in two rounds by Brian Nielsen. How about “Blackjack” Billy Fox – immortalised in Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull winning a fixed fight against Jake LaMotta – who was 36-0 with 36 knockouts at one point despite being relatively talentless?

The point here is that gaudy records like Wilder’s are not hard to come by; it just takes a wily promoter and a willing audience. Wilder had the former, but a credulous public was yet to emerge for him. That would begin to change when he rematched Bermane Stiverne, the only one of Wilder’s Clown’s Alley opponents to last the distance. Stiverne, who had effectively retired since his unimpressive first fight with Wilder, looked fat, old, and disorientated; in other words, there just to get paid. Wilder duly dispatched the 39-year-old Haitian-Canadian with characteristically unschooled windmilling hooks in the first round to erase the one blemish on his perfect(ly absurd) résumé.

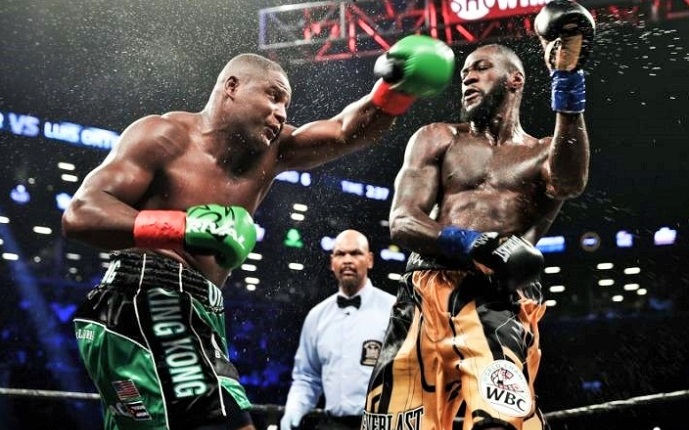

That win marked the sixth title defence by the “Bronze Bomber” of the WBC belt he had won from Stiverne. The seventh would require an apparent step-up in class against the highly rated Luis Ortiz. I should say “formerly” highly rated, as to people following his career, the undefeated Cuban had been on the slide since he failed to finish Malik Scott inside the distance and struggled with the game but sub-par domestic-level heavyweight Dave Allen, more recently the victim of an absolute hiding from David Price. Ostensibly 38-years-old but looking closer to fifty, Ortiz went into the fight against Wilder the underdog with both the bookies and every expert pundit. He made a decent fight of it, out-boxing Wilder and nearly ending it in round seven, but the Bomber rallied to another KO victory in the tenth.

Despite his evident decline, Ortiz was still a strong name to put on the record, a name that Wilder’s team knew would lend some much-needed credibility to their fighter. And indeed, the talk around Wilder began to change. Yes, he was lanky and unsophisticated, but his right hand seemed to possess something akin to genuine power. Okay, so he’d only got the TKO against a past-it Chris Arreola because of a corner retirement, only got the initial shot at Stiverne’s title after Malik Scott sat down for ten after a phantom-punch, and yeah, he couldn’t finish Stiverne until after Bermane had spent two years putting away cream cakes and cookie dough, but now Deontay had finally beaten a legitimate fighter inside the distance.

The turkey had tipped the scales, and someone, probably Haymon, decided Christmas had come at last. But with the real money fight against Anthony Joshua unavailable, Wilder’s team picked up the phone to Frank Warren and a deal was struck to unify the Deontay’s belt with Brit Tyson Fury’s claim to the lineal heavyweight championship.

The one thing Tyson Fury has never been accused of being is a smooth technician, but I for one predicted Fury would easily out-box the almost comically unschooled Wilder, unless the American could catch him with one of those absurdly powerful right swings. Though Wilder in full flow looks like he’s campaigning for a bout with Don Quixote, I reasoned that anyone who can knock out the sturdy Luis Ortiz can do the same to Fury.

Although it’s difficult to know exactly what Wilder’s handlers were thinking, there must also have been a suspicion that Fury was past-it since his very public decline, which saw him mired in drug use and ballooning to over 300 pounds after winning the heavyweight championship from Wladimir Klitschko. In the interim he hadn’t trusted himself to get in the ring with anyone more dangerous than Francesco Pianeta, whose distant prime years had included a hammering sixth round TKO from Klitschko. (Pianeta lasted the distance against Fury.) Who exactly was the turkey here?

Sure enough, this two-bird roast ended all-square. Fury out-boxed Wilder with contemptuous ease, but dropped four points thanks to two knockdowns, which was enough to give the judges the excuse they needed to call it a draw. No surprises really, but something about the drama of that second knockdown sparked spectators’ imaginations, and the fire quickly spread through the media and industry commentators.

Here’s what happened: in dodge-ducking Wilder’s jab, Fury dropped his shoulder guard just enough for Wilder to sneak a right straight down the pipe. As “The Gypsy King” began to drop, Wilder threw a left hook that caught the Briton’s chin hard enough to change the direction of Fury’s fall. It looked spectacular, and every single onlooker thought Fury had to be out cold. Everyone, that is, except referee Jack Reiss, who began a surely unnecessary ten count, which Fury then somehow beat. Back on his feet, and showing no ill-effects from the hitherto devastating-looking punches, Fury clowned Wilder for the rest of the round, apparently assuming the judges had watched him dismantle his opponent right up until his nine-and-three-quarters of a second break on the canvas.

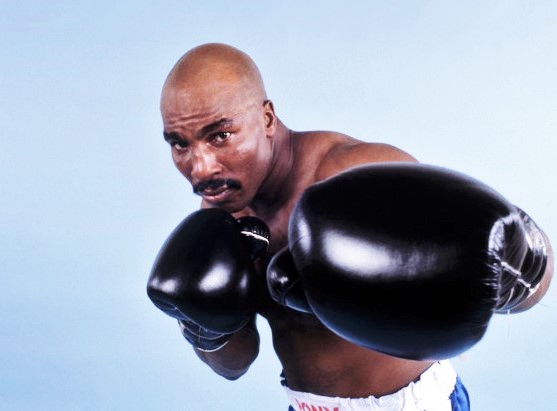

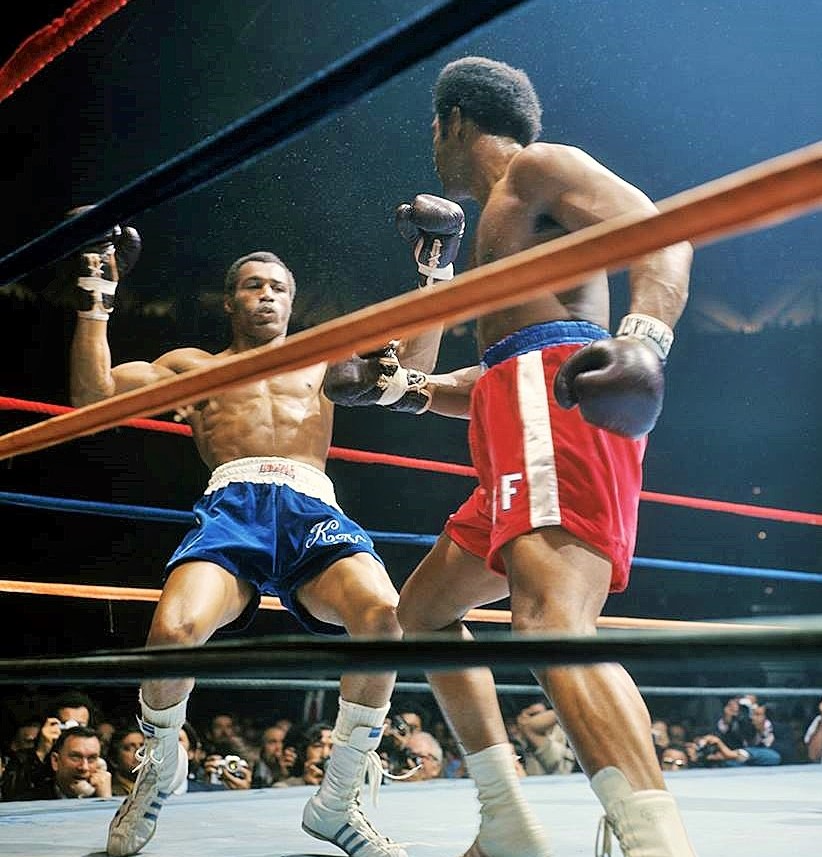

A bizarre circular narrative then began, and hasn’t stopped to date. It goes something like this: in getting back up from Wilder’s combination, Fury had proven himself to have one of the greatest chins in boxing history, his rise comparable with Larry Holmes’ Lazarus moment against Earnie Shavers in 1979. At the same time, in knocking down and nearly finishing Fury, the possessor of such insuperable whiskers, Wilder had proven his pedigree as one of the most lethal punchers ever.

This despite the fact that Wilder hadn’t achieved anything beyond cruiserweight Steve Cunningham, who also had put Fury on his arse in the second round of their 2013 bout, or lightly-regarded Nikolai Firtha, who had done the same two years earlier.

This insanity was only galvanized at the end of 2019, when Wilder gave a dubiously 40-year-old Luis Ortiz a pointless rematch. A knockout win for Wilder was the widely expected result, though some commentators, perhaps wishing the buying public to remember Ortiz’s pedigree five or six years previously, had temerity enough to label the match as “intriguing.” A faded Ortiz again won most of the rounds, before inevitably succumbing to one of Wilder’s right-hand bombs.

In the aftermath of this farce, Bob Arum called Wilder “the hardest punching son of a bitch I have ever seen.” Respected boxing analyst Lee Wylie wrote on Twitter that Wilder “might be the most surefire, one-punch KO artist I’ve ever seen,” and asked whether there was “anything more inevitable in boxing than a Wilder KO?” (Perhaps only Chris Arreola, Bermane Stiverne, and Tyson Fury can answer that one, although Johann Duhaupas also finished his fight with Wilder on his feet.) Stephen Edwards, the trainer of light-middleweight champion Julian Williams, opined that Wilder was already guaranteed a Hall of Fame spot when he retires, and put the Bomber’s punching power dead even with that of Shavers and George Foreman, and ahead of Sonny Liston.

It gets better. BBC boxing reporter Mike Costello called Wilder the biggest puncher “I’ve seen in my lifetime,” which would include Foreman, Shavers, and Mike Tyson. (In the same conversation, Steve Bunce diplomatically began a sentence with “I don’t want to sit here and say ‘he’s the greatest of all time’…” as though catering for the family of Muhammad Ali who might be listening, or implying that only the comfortable venue of a BBC recording studio might render the sentiment inappropriate.) Ben Davison, Tyson Fury’s now ex-trainer, went further and said that not only was Wilder the biggest puncher in the heavyweight division’s history, but the biggest puncher in boxing history. Wilder himself reiterated his belief that he hit harder than that mythic entity, the Prime Mike Tyson. (If the 53-year-old Tyson came out of retirement and fought Wilder tomorrow, it would be a fifty-fifty fight.)

Only in our era of cultivated Philistinism could this tsunami of panegyric ejaculate be conceivable. Let’s recap for a moment. In fights against real (if faded) fighters, by which I mean boxers who have actually shown a modicum of ability, resilience, brains, and power, Wilder is 2-0-1 (but really 2-1) with two knockouts, neither the instant lights-out moments his current reputation suggests. His one truly chilling knockout was against Dominic Breazeale, no wilting violet resistance-wise, but hardly George Chuvalo, who George Foreman was beating to death before the referee stopped the fight, or the mythically tough journeyman Scrap Iron Johnson, who was also saved from Foreman’s onslaughts. That’s before we get into Joe Frazier, Ron Lyle, Ken Norton, Gerry Cooney and the other top-level guys Foreman pulverized. (His pole-axing of Cooney is like watching a scene from George Franju’s landmark film Blood of the Beasts, in which a horse’s life is instantly ended with a gun shot between its eyes.)

In a direct comparison, Wilder’s right cross probably does merit comparison with any one punch of Foreman’s, or indeed Tyson’s. Few fighters in history have had a single shot in their arsenal so far beyond every other aspect of their combative make-up. It’s perhaps comparable to welterweight Danny Garcia’s left-hook, in that it’s the only thing about them which is exceptional. Imagine for a second, though, that right hand landing on the chin of 90s heavyweight Oliver McCall. What would Wilder do when his vaunted equalizer bounces off to little effect? I’ll tell you what Foreman would have done: bully McCall into the ropes and wail away at him until the referee’s stomach turned. I’ll tell you what Tyson would have done: bob-and-weave and bludgeon his way to a decision victory, like he had to do several times against bigger, more durable fighters.

Wilder is incredibly fortunate that there’s nobody around with the chops to gobble up his admittedly legit right hand. Are we so sure, just because it beat Luis Ortiz and a laundry list of no-hopers, that it could end Evander Holyfield’s night? How about James Toney? Or Rocky Marciano? If so, is Tyson Fury (knocked down four times to date) therefore more durable than them? How come it didn’t immediately switch off notoriously chinless bum Audley Harrison, Blood of the Beasts-style, despite landing flush?

The perception of Wilder is the consequence of perspective, or lack thereof. Wilder holds a belt he won off Bermane Stiverne, therefore he is a champion. Wilder has defended that belt ten times, therefore he has tied Muhammad Ali’s record and is guaranteed a Hall of Fame slot. Wilder’s knockout ratio is ninety-eight percent, therefore he’s the best puncher ever. These facts are never seen within their less convenient contexts, like the fact he has never unified belts, or beaten a lineal champion, or that second in the listing of all-time heavyweight knockout ratios is Daniel Dubois. His padded record, combined with the collapse in prestige of Anthony Joshua since his unexpected loss to Andy Ruiz Jr., has left him looking like the true kingpin of the top division, with only Tyson Fury able to contest his supremacy.

We therefore have a unique event in marketing history: a plump, overfed turkey re-branded as a sleek bird of prey. The only astonishing thing is how many people have bought it. — Laurence Thompson

Was it Firtha who first knocked Fury down? I seem to recollect that it was former Canadian Heavyweight champ Nevin Pajkic.