Canelo vs Bivol: End Of The Myth

It had existed for some time, in the background, like a rarely acknowledged rumor, a notion, a theory. And then it came to full flower, suddenly, around the time some 26 million people tuned in to see him defeat Rocky Fielding, a widely held conviction, and one not to be questioned: Saul “Canelo” Alvarez is the best boxer on the planet and a future all-time great, our star, our standard-bearer, the fighter who transcends the sport. He was that figure-head we’re seemingly always looking for, that conglomeration of talent, achievement and celebrity status which reassures us that this archaic blood sport is still relevant, still popular, part of the mainstream. No one could question Canelo’s drawing power or his accomplishments, his record studded with the names of title-holders and champions. After a series of major wins, he was positioned perfectly to reign, for years to come, as the face of professional boxing.

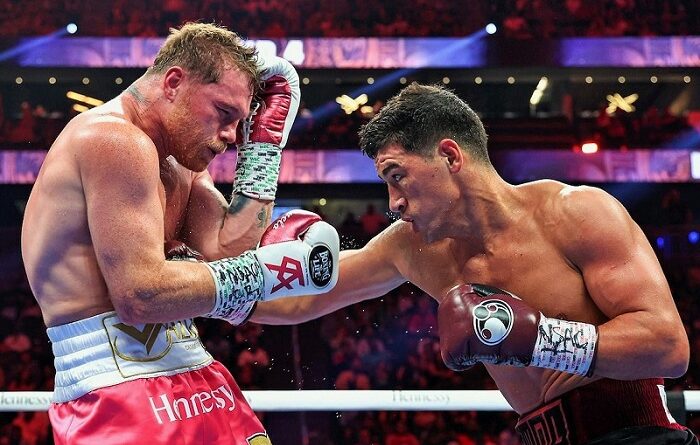

And then, this past Saturday night, that conceit became a phantom, a mirage, a figment of our imagination. For ardent fans of Canelo, it is now a brief and glorious interlude fixed in the past, gone with the wind. The man who brought this fantasy to a screeching halt is one Dmitry Yuryevich Bivol, an unassuming Kyrgyzstan who has quietly established himself over the last few years as arguably the best light heavyweight on the planet, second only to Artur Beterbiev, with convincing wins over Isaac Chilemba, Jean Pascal, and Joe Smith Jr. Despite this, most saw him as another notch on Canelo’s belt; while some regarded him as a dangerous challenge for the Mexican juggernaut, precious few were picking him to win.

But win he did, and with authority, the match almost as one-sided as Canelo’s loss to Floyd Mayweather Jr. back in 2013. Most ringsiders had at least eight rounds on Bivol’s side of the ledger, and as the bell rang to start the twelfth and final round we were left to contemplate a wholly unexpected circumstance: Canelo needed a knockout to win. He didn’t get it, and as the judges’ rather narrow scores were announced one could hear in the background that unmistakable sucking sound, like an overburdened vacuum or a monstrous toilet, as millions of dollars, huge sums set aside for Canelo’s future triumphs, suddenly disappeared.

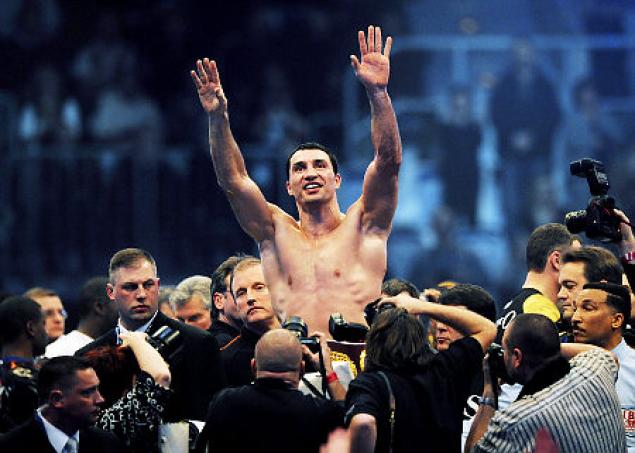

It makes one wonder: where did this notion come from, this idea that boxing must have a single great star around which the rest of the sport coalesces, the other champions like planets orbiting an incandescent sun? The conviction seems to be that without such a figure the sport cannot draw big crowds and big paydays, cannot compete with football or basketball for sports fans’ attention and disposable income. Or is it less about that and more about there being a single person who gets to hoard the biggest purses all to himself, the desire to be the unquestioned king, the one-and-only transcendent boxing star, as Muhammad Ali or Sugar Ray Leonard once were?

In any case, there can be no doubt that many fans, and more than a few talking-heads in the boxing world, had punched their tickets and gotten on board for the Canelo ride, with the expectation it would be a long and wondrous one. For evidence, look no further than this past December when people were putting together their year-end, Best Of 2021 lists, and virtually everyone was singing from the same hymn book: Saul “Canelo” Alvarez was an absolute lock for Fighter of the Year, this despite the fact that Callum Smith, Avni Yildirim, Billy Joe Saunders and Caleb Plant collectively represented virtually no threat at all to the five-time world champion. (Ed. note: It’s worth recalling that The Fight City sang a different tune.)

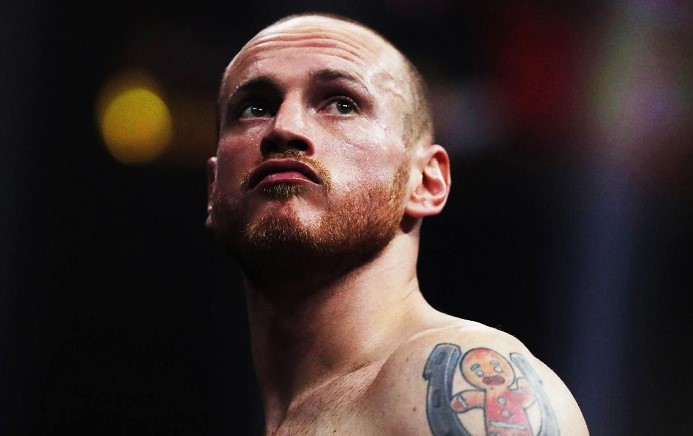

There has always been something rather contrived about the whole “Canelo Alvarez is the face of boxing” trope, requiring as it always did a willingness to overlook and forget. Those who disputed it and cited certain inconvenient truths were hushed and shushed and shown the door, but that didn’t change the fact that Gennady Golovkin clearly got the better of him in their first meeting in 2017, or that the scorecards in his battles against Austin Trout and Erislandy Lara were somewhat questionable. And then there’s the various weigh-in and catch-weight shenanigans, the shameless avoidance of Golovkin, both before and after that first fight, all this without bringing up the failed tests for performance-enhancing drugs. So many were bending over backwards, not to mention bending the truth, in order to puff up the fighter, make him bigger, so he could, hopefully, become bigger-than-life.

And now this: Canelo vs Bivol proves to be a surprisingly one-sided victory for a fighter few cared about and, outside of hardcore fans, not many had even heard of. In the days leading up to the bout, those in the pro-Canelo camp kept harping on how courageous the Mexican was to take this fight, to challenge himself, to attempt to make history, ignoring the fact that, well, that’s what a great boxer is supposed to do, that after a diet of Yildirims and Plants, Saul was in arrears in terms of giving fans a match-up they could get truly excited about. And yet they weren’t. Despite the best efforts of the Canelo cheerleaders, the oft-heard lament of recent days was that something was out of joint, that it just didn’t feel like a Canelo fight-week.

Something weird is going on when the hype is far louder for Canelo vs Caleb Plant than for Canelo vs Bivol, and I for one have no idea what that is exactly. It’s fair to say that the marketing department at DAZN or Matchroom, or whoever was supposed to get us stoked for this fight, dropped the ball. With all the talk about “legacy” they unwittingly framed the match as essentially a foregone conclusion, instead of making all aware of the very real threat that Bivol represented. As a result, Canelo’s defeat feels like a great disappointment instead of a noble effort against a naturally bigger and stronger fighter who brought serious pedigree and past accomplishments to this clash. Canelo himself reinforced this view with his post-fight petulance, insisting he deserved the decision, that Bivol won, at best, four or five rounds. Our perceptions are always skewed by our expectations, or lack thereof, and in this case it’s Canelo’s standing and image that will suffer.

All this only puts another nail in the coffin of the Canelo myth, the idea that he is something more than what keen observers already knew him to be: a very talented but also very calculating competitor, a boxer who, while being a huge draw, somehow can’t quite fill the big shoes which everyone wants him to fill. He may come back and defeat Bivol, and then beat an aging Gennadiy Golovkin, maybe a David Benavidez too, all of that is possible. He’s already had a remarkable career, and he can still go on and have an historic one, but the myth of Canelo was that he was more than a gifted boxer and a champion, much more than another name on the pound-for-pound lists. It says something interesting about today’s version of professional prizefighting that it needed him to be more, that so many wanted him to be the brilliant, blinding sun around which everything else could orbit. But we’ll all just have to get by with something less dazzling, won’t we.

— Neil Crane