À La Prochaine, Montreal

Montreal is “The Fight City,” not Toronto. Or so we thought. And still think, as any objective evaluation of Canada’s two largest urban centres reveals a mismatch in terms of which metropolis possesses the greater number of both legit fight gyms and fight cards, amateur or professional. Factor in mixed martial arts and such globally renowned institutions as Tristar Gym, and it goes from “mismatch” to “no contest,” a bout no athletic commission would ever approve. Simply put, combat sports are part of the life-blood of Montreal; one cannot say the same for the city once called “Hogtown.”

Adonis Stevenson vs Badou Jack is an attractive match-up no matter where it’s held and, according to Groupe Yvon Michel, it was signed and sealed for May 19th at the Bell Centre quite some time ago. Posters had been printed, television spots produced, and eye-catching brochures with both Stevenson’s and Jack’s faces on them were prominent at GYM’s most recent Montreal Casino cards. But there was one significant problem which the local fight crowd had noticed and kept wondering about: why were tickets not on sale?

That wasn’t the only sign that something wasn’t right. Shortly after GYM made an official announcement of the event being booked for the Bell Centre, Adonis Stevenson himself let it be known through social media — amidst his many selfie videos of holidays in exotic locales or singing along to Earth, Wind & Fire inside his Ferrari (or is it a Lamborghini?) — that the public should not necessarily believe everything they were being told. At one point he even went so far as to state definitively that his next fight would be in Toronto, not Montreal. According to GYM at the time, this was a misunderstanding.

But confusion of some degree or another has reigned ever since. That is until three days ago, when it was made known, unexpectedly yet unequivocally, that Stevenson vs Jack for the WBC light heavyweight title will in fact be staged in Toronto, not Montreal. Given that the date for the event has not changed, this remains, to some degree at least, a “believe-it-when-we-see-it” affair. The task now is to organize a major boxing event in a different city, and with a different athletic commission, and to successfully promote it, all in a span of less than one month. Even with the combined resources of GYM, Lee Baxter Promotions, Maple Leaf Sports and Entertainment, and Mayweather Promotions, if they can pull this off to everyone’s satisfaction and realize a legitimate financial success, it will have to be regarded as an astonishing feat, if not a minor miracle.

But why take the risk? Why, when a venue and date were already booked, choose to scramble to put together a promotion in a city where boxing simply does not have the deep roots that it has in Montreal, in a city which hasn’t hosted a truly major boxing event in decades? When Stevenson defended his WBC belt there against no-hoper Tommy Karpency in September of 2015, it was in fact the first world title match held in Toronto since Hall of Fame champion Aaron Pryor defeated Nicky Fulano way back in 1984. Stevenson vs Jack is, at least on paper, a more attractive match than either of those bouts, and yet the plan at present is to have only seven thousand seats available at Toronto’s Air Canada Centre. Can there be any doubt that significantly more tickets would be sold in Montreal for this intriguing duel between two experienced champions?

At the moment there doesn’t seem to be a clear or satisfying public explanation for the drastic move to a different city. It seems that Groupe Yvon Michel proceeded under the incorrect assumption that they, as the actual organizers of the event, could decide its location. Did something get lost in translation or overlooked in the fine print? The lack of any clear, understandable rationale for this sudden change only leaves Montreal fight fans more frustrated and allows for all kinds of baseless speculation. Not a good look for anyone.

“I was informed that, for important business reasons, they were forced to bring the fight to Toronto,” Yvon Michel told interviewer Dave Morissette two days ago. “Of course, I was disconcerted, extremely frustrated … [but] we are professionals.”

Two hastily called press conferences were then held, the first on Tuesday at the Air Canada Centre in Toronto; and naturally, everyone was singing from the same songbook.

“We are looking forward to hosting this spectacular event,” said Wayne Zronik of Maple Leaf Sports & Entertainment.

“There’s a market for [Stevenson vs Jack] because there are close to seven million people here,” declared Baxter. “If we get it out there, there’ll be people who want to attend this.”

“Fans love big events, and they will come out for big events,” chimed in Ellerbe. “And an event like this is highly anticipated: the best fighting the best.”

“This is a big sports city – you have the Raptors, you have soccer,” said the WBC champion himself, adding: “Everything Toronto touches is successful.”

The second press conference took place yesterday at Montreal’s Tavern 1909, the downtown restaurant named after the year the Montreal Canadiens were founded. It was a perfunctory affair, notable for the presence of Lamont Jones, Vice President of Haymon Boxing Management, a clear indication that the mysterious Al Haymon is very much involved in how this promotion is unfolding. And, in keeping with his employer’s modus operandi, Mr. Jones declined questions or interviews at both press conferences.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of yesterday’s otherwise uneventful presser was the number of times the name Eleider Alvarez was mentioned, as different people, including Adonis (when pressured by Yvon Michel), acknowledged the other top light heavyweight fighting out of Montreal, and the fact that without his cooperation, a match with Badou Jack would be even more difficult to make happen than is currently the case.

Theoretically at least, “Storm” Alvarez was Stevenson’s mandatory opponent, as dictated by the WBC, and his consent had to be secured before Adonis could face anyone else. Of course, this was also true for, at minimum, Stevenson’s two previous matches, a repetitive process which has made a mockery of the WBC (not that they haven’t been one for decades) and their rankings, and only further reinforces the perception that Stevenson is avoiding the most threatening of opponents. Alvarez, who has in fact bested stronger competition than Adonis over the last few years, is now set to face the man many believe Adonis wanted nothing to do with, Sergey Kovalev. And this may mean Alvarez will be contractually obligated to HBO for the foreseeable future, thus making Stevenson vs Alvarez a virtual impossibility.

For Stevenson’s part, when confronted with some difficult questions at yesterday’s press conference — for which he arrived 45 minutes late; he was on time for the Toronto presser — his answers were uniform: ask Al Haymon. It’s Haymon who decides who he fights; it’s Haymon who decides where he fights. Needless to say, this explanation is too convenient to be taken seriously.

Instead, out of all of the statements made at the two pressers, Stevenson’s “Everything Toronto touches is successful” is perhaps more revealing. At this point one can only speculate as to the precise nature of the “important business reasons,” as Michel put it, which compelled this event to abruptly move from Montreal to Toronto, but it seems reasonable to speculate it may have involved a strong push from Adonis himself. And when the fighter states that all “Toronto touches is successful,” it’s difficult to overlook the implication that, in his mind, such is not the case for Montreal. Might less-than-overwhelming attendance figures at Stevenson’s last bout, held at the Bell Centre in June, be on the WBC champion’s mind? Or the different times he’s been booed in his home city? Or perhaps Montreal’s disastrous hockey season? What, exactly, has happened, Adonis? How did we let you down?

Of course there is another factor at play here, and which no one involved in this promotion wants to talk about, and that is the appeal of Adonis Stevenson, which is to say, the lack thereof. Having won his world title with an electrifying one-punch stoppage of Chad Dawson back in 2013, Adonis is now one of boxing’s longest-reigning world champions, but he is also one of its least popular. There are two reasons for this. One is that since becoming champion he has faced two opponents who represented legitimate threats, those being Tavoris Cloud and Tony Bellew, the fighters he battered in his first two title defenses. Those wins, along with his knockout of Dawson, made him our Fighter of the Year for 2013.

But since then, and after signing on with Al Haymon, he has stepped into the ring only six times, all of the matches against opponents that, at least in the eyes of the public, represented no serious competition (the possible exception his knockout of Thomas Williams Jr., who was coming off an impressive stoppage of highly touted Edwin Rodriguez). And so he is perceived as a champion who has avoided meaningful showdowns against the likes of Kovalev, Joe Smith Jr. and Bernard Hopkins. Yvon Michel, to his credit, has repeatedly defended his fighter and maintains this is not the case, but even so, Stevenson is viewed by many disgruntled boxing fans as the quintessential “Haymon fighter,” a pugilist who seeks only the matches which represent the least amount of risk. One senses that, should he triumph on May 19, it may take more than a single significant win against an elite-level pugilist to dispel this perception.

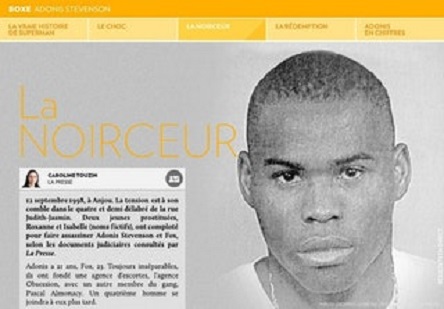

But of course Stevenson’s lack of popularity cannot be discussed with any degree of honesty without bringing up his criminal history and the time he spent in prison. Years before his professional boxing career began, Stevenson was involved in organized crime and he was eventually convicted of charges of assault, issuing threats and the managing of prostitutes. He served four years in prison and was released in 2001. Very little of this was known when Adonis first rose to prominence on a series of knockout wins that began in 2006.

As one might expect, after he became a world champion, the truth came to light, and in the most damaging manner, with a lurid account of criminal activities written by Caroline Touzin and published in Montreal’s La Presse on November 23, 2013, just before Stevenson’s bout with Tony Bellew. Less a profile of Adonis and more a chronicle of violence and sadism, what is less known is that, according to Michel, Touzin never indicated to Adonis that she was working on anything other than a generic profile of Montreal’s newest boxing champion. One can only speculate as to why the boxer would trust her to the extent that he would bring her to his home and have her meet his family, but knowing this, it is not difficult to imagine how he regarded the final result. Ever since, interactions by Adonis with the media have been restricted to press conferences for his fights and nothing more. This writer’s repeated requests for an interview have gone nowhere.

Which is, of course, counterproductive. No doubt he has his own story to tell and if ever an athlete stood to benefit from letting the public get to know and understand him, it is Adonis Stevenson. Personally, I fail to understand why those who would otherwise root for an underdog, or offer compassion to a person trying to overcome addiction or personal trauma, would not also be supportive of those who have served hard time. What more can be asked of those found guilty of a crime than to pay the penalty meted out by the courts? Once that is done, do they not deserve the public’s acceptance if they have in fact mended their ways? When we condemn and dismiss those who have been tried, sentenced, jailed, and released, what are we saying to those who earnestly wish to turn their lives around and rejoin society?

One wonders why the Adonis Stevenson story is not one of redemption, of a man who was lost, but who emerged from prison determined to succeed, who dedicated himself to his difficult craft and, against long odds, became a world champion. It may be worth mentioning that the people Touzin interviewed for her squalid tale are those Adonis turned his back on after he emerged from incarceration, determined as he was to never again be involved in criminal activity. And it may also be worth noting that this writer has spoken to several individuals from the Montreal boxing scene who have worked with Adonis and all refer to him as a most likable person, not to mention a doting father.

But no one in the public knows this, as no counterpoint to the Touzin article has ever been made available. All sports fans know, all they can know, both in Canada and elsewhere, is a boxing champion who appears both arrogant (his over-the-top ring celebrations and awkward trash talk drawing much attention), but at the same time less than anxious to face the best competition available, and who, years ago, was a criminal. Little else has been presented, aside from posts on social media showing an exuberant Stevenson enjoying himself in exotic locations and singing hip-hop songs in his Ferrari (or is it a Lamborghini?), while his rare public appearances are always shadowed by two huge bodyguards, which only makes him more difficult to relate to. And thus those who are indifferent to Stevenson, or actively resent him, are legion, while actual fans remain almost non-existent.

And so when one reflects on how a major boxing event has inexplicably moved, at the last possible minute, from Montreal to Toronto, one wonders if it has something to do with a yearning on Stevenson’s part for new beginnings, second chances, the attraction of a city where, in his mind, not only is “everything … successful,” but where the shadow of his past is less present, less tangible.

But what about all the people here who helped you get on the right road, Adonis? Who believed in you, invested in you, made your journey to the top possible? All of whom are in the city you don’t want to fight in anymore? One wonders if they may already be in your rearview mirror as you say, “À la prochaine, Montreal!” and speed west on the 401 in your Lamborghini (or is it a Ferrari?), your final destination the bright lights of a bigger metropolis. But not a fight city. — Michael Carbert